-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Translations | Memoir

Share -

A Scrapbook of Memories and Reflections: by Ketaki Kushari Dyson [Parabaas Translation] : Ketaki Kushari Dyson

A Scrapbook of Memories and Reflections Ketaki Kushari Dyson

Jon Wisenthal, Me, a fellow student called Margaret,

and Leslie Holden, maybe 1962 (left to right).

Photo taken during a holiday in Wales.At 111A Rasbihari Avenue my father was in his seventh heaven to be just a brisk walk away from no. 202, which housed the poet Buddhadeva Bose and his magazine Kavita. My father knew Bose from their days at Dacca University and subscribed to the magazine Kavita, which he read regularly. We knew all the members of the Bose family and visited them from time to time. Mrs Bose treated us kids with Bengali sweets like a typical auntie, while Bose and my father discussed literature in the next room — discussions which were punctuated by loud explosions of laughter in the East Bengali style. The connection has of course been a special privilege in my literary life. I have translated Bose’s poetry and written about him and his work in another substantial book. Some of my translations of Bose’s poems into English have been re-translated into Finnish by Hannele Pohjanmies.

When Bose started translating poetry from French and German into Bengali, he would sometimes ask my father questions connected with that work, which my father enjoyed answering, as by then he was pretty good in these two languages. After my father was officially allocated a phone at home, which was in 1950, my father had sometimes to be phoned at the Bose household and reminded to come home for his lunch. Those were happy and exciting days for my father. He also knew the poet Ajit Datta, who lived with his family on the floor above the Boses. This poet was also known to my father from their days at Dacca.

At the time of India’s Independence, officers like my father who worked for the Bengal civil service were given the option of choosing between India and Pakistan for their future careers. My father opted for India as he did not like the idea that our country had to be divided on religious grounds. After Independence he was inducted into the Indian Administrative Service. My uncle Shonu entered the same service by taking the new formal IAS exams. I believe he belonged to the first batch of people to take those new exams. Professionally it was an exciting time for them. They discussed their job-related problems all the time with much passion and were happy to be working for the new India.

I have talked about the balcony at the Rasbihari Avenue apartment so many times already. I should mention that it was also there that I first heard from my father about the poet Jibanananda Das and his financial problems. Das died somewhat prematurely after a collision with a tram and I never met him.

I have already touched the subject of going to school. It was only after coming to Calcutta that my parents decided that I needed to start formal schooling. Their choice fell on St John’s Diocesan Girls’ High School, as it was then called, at the junction of Lansdowne Road and Elgin Road. It was a highly respected institution with an excellent academic reputation, run by Bengali Christians. Many parents wanted to send their daughters to it. Not so long ago I was delighted to learn that an Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, had visited it when he was in Calcutta.

In my time the school taught in the medium of Bengali up to Class VI, then switched to the medium of English from Class VII onwards. School Final Examinations were taken at the end of Class X, after which, in those days, one had to leave school and go to a college to study for the Intermediate Arts or Sciences, I.A. or ISc.

When I was assessed for entry, the school found me fit to be admitted to Class VI, but recommended that it would be unwise to put me into a class with girls too senior to me in age. They admitted me to Class V, and I started in June 1948, when the school re-opened after the summer recess. I was two years younger than the girls in my class. At first I travelled by the school bus, and when I was a little sturdier, I used to take the 8B bus. Deshapriya Park, Lansdowne Road, the shop at P. Mazumdar, the hawkers’ stalls — these were home territory for me in those days. We had relatives on Lansdowne Terrace.

This is perhaps a good juncture in which to mention that at some point after coming to live in Calcutta on a more permanent basis than before, and after starting school formally, I developed a tendency to get attacks of asthma from time to time. The city’s dust was blamed, as was the humidity of the rainy season.

There was a doctor in Calcutta investigating why some children developed asthma while others did not. I think he was also looking at the links between diet and allergies. I was one of the children he looked at in his research project. It says something about my parents and their respect for science that they let me be a research subject in this way.

There was indeed something dramatic about the way I developed asthma after coming to live in Calcutta and starting school. I had never suffered from it before. I never got asthma when I visited Calcutta for a few days with my parents at the time of the Puja break. Of course, the Puja visits happened when the monsoon season was over. As I have said, I started school in the middle of 1948, when schools re-opened after the summer break. There would be no escape from the rains or humidity at that time. I suspect my asthma had little to do with monsoon humidity as such, to which I had been exposed ever since my birth. I had watched enough of the rains every year. There was something else in the urban environment which was triggering my asthma, most probably the exhausts of cars and buses.

With hindsight I now realize that we never got the full picture. We only had segments of it, which we could not put together. In my childhood I was sometimes allowed to accompany my father to the countryside. The journey would invariably be by jeep and we would always be exposed to plenty of dust. One of my childhood poems, written in Bengali, of course, referred to ‘one mustard field coming after another’ and to ‘dust, dust, and dust floating everywhere’. But this kind of occasional exposure to dust did not seem to trigger any problem. Perhaps there was something else in the atmosphere of the big city that was not there in the countryside or the smallish country towns of those days. It was perhaps a more complex environmental pollution. In Calcutta we were exposed to real urban traffic, streams of cars and buses, including double-deckers, and in those days they must have run on whatever kind of petrol that was then available, however crude that might have been. Once I started going to school, the exposure to the exhausts of buses happened of course on a daily basis.

The other question that used to be discussed a little bit after this period was whether the removal of tonsils played a role in the development of asthma in children. This question really bothered my mother. She saw how, after my tonsils were removed, my singing voice was adversely affected. I had difficulty in raising my voice to the higher notes and sustaining it there. I would give up, put my head down on the harmonium, and cry inconsolably. For my mother this was devastating to watch, because she had so much wanted me to learn to sing.

I might have been about nine when my tonsils were removed. The operation was done in the Out-Patients of the Medical College Hospital. I remember being muffled by the chloroform. In those days tonsils were frequently removed if children developed coughs and colds. Growing up in England, Robert also had his tonsils removed.

There seems to be a period in children’s lives when they catch colds easily. If they are allowed to get better without too much interference, they develop a certain immunity. Robert and I tried this method of minimum interference with our own children, and it did work. Doctors eventually came round to this path of minimum interference.

After it was clear that I could not, as it were, become ‘a singer’, my mother tried to make that a project for my youngest sister, ten years younger than me. And she succeeded. Koyeli did indeed learn to sing, and in addition to her other academic qualifications, became a graduate of the Bhatkhande School of Music also. There was no way that my mother would have allowed her youngest daughter to have her tonsils removed!

There may well be a connection between our genetic inheritance and the way we develop allergies. As I have already noted, my mother’s paternal grandmother living in Benares suffered from asthma, to counteract which she inhaled datura, as was sometimes done in those days. Illnesses do often run in families and some may well think that it is not polite to talk about them. But we can never make progress in our understanding of the world if we allow that kind of politeness to prevail. Thankfully in present times there is a move away from that philosophy of silence and towards greater realism and honesty. Some will undoubtedly maintain that in fact we have veered to the opposite extreme of washing our dirty linen in public, and if anything, doing it far too vigorously. But it is only people who acknowledge the existence of problems and do not sweep them under the carpet who can actually find solutions to those problems.

My third and fourth siblings are seven and ten years younger than me. One advantage of seniority is that you do learn to deal with your younger siblings almost as a mother would. You learn about mothering, and about the tricks that children play to get their own ways. In the days of large families, younger children were indeed brought up to a large extent by their elder siblings.

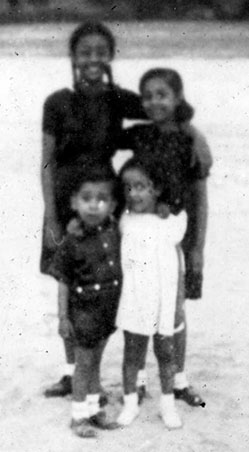

Me with Karabi, Amit and cousin

Urbashi DasguptaBy observing my mother closely when she gave a bath or fed solids to her youngest child, I had a lot of opportunity to learn how such activities were managed. At some point my mother reckoned that I was competent enough to do these things even without her supervision. Very occasionally she left her youngest child nominally in my charge when she went to see a film with my father. I say ‘nominally’ because her utterly trusted man of all work, Kashi (presumably short for Kashinath) would be there to back me up if necessary. Kashi was like an uncle and guardian to us. He was a representative of that unique class of men in domestic service in those days, who were from the landed and farming communities of Orissa and who came to Calcutta to supplement their family incomes through domestic service. Kashi was a brahmin and wore a sacred thread, which he occasionally tucked behind one of his ears. He was 100% trusted by my parents to do all the essential shopping, helping with the cooking as necessary, being in charge of us children when they themselves went out, and even for withdrawing cash from the bank. We could not play tricks on him. He would tell us off if necessary. The relationship that developed between such men and professional Bengali families in Calcutta was very special from the viewpoint of social anthropology. In the home of my relatives at Palit Street in Calcutta, where I stayed when studying at Presidency College, the cook, also an Oriya brahmin, was a similar character. He was quite a chef, in charge of all the meals consumed in a very large household, which had a refrigerator in the dining-room. The women of the family assisted him in the morning by chopping phenomenal quantities of fresh vegetables on their pedestalled knives, which were upright and slightly slanted.

I have vivid memories of trying to feed my youngest sister. For what I had to do ‘administering food’ would be a more accurate description than ‘feeding’! She must have been teething and had lost all appetite. I would offer her a spoonful of food and she would move her head the other way. I would move the spoon where her mouth now was, and she would then turn the other way. This kind of offering and rejection went on and on and on. I tried to distract her by pointing to birds. ‘Look, here’s a sparrow!’ Or: ‘Goodness, look at that crow! It seems to want your food!’ My sister couldn’t care less about that. She wouldn’t mind if I gave the crow the entire bowl of whatever was on offer.

Years later, my younger son used to play the same trick on me. He was teething too, and would move his head exactly like that, first to one side, then to the other side, refusing every spoonful of nourishment. When he did that, I used to be vividly reminded of my youngest sister. Luckily we found that he never turned down our home-made yoghurt and during a period lived almost entirely on that.

To balance the feeding problems I encountered when dealing with my little sister when she was presumably teething, I have very happy memories of teaching her to read, using Tagore’s Sahaj Path. That was a pleasurable and rewarding experience. I still remember the sheer joy of it.

But boys will be boys, as the saying goes. When my brother was about three, he developed a special trick to show off his skills. He would throw things off the balcony of the third storey. They would land on the pavement below. Someone would have to run and fetch whatever had been thrown, and my brother would giggle, as if saying: ‘Now you know my powers, now you know what I am capable of achieving!’

One rainy day he threw my geography textbook, The World by Dudley Stamp, a classic textbook of those days, to the pavement below in this manner. I scampered down the stairs as fast as I could to rescue my precious book from this predicament. An elderly working-class widow in white passing by had picked it up and was looking at it with some curiosity. I am sure she could not read English, but she could plainly see that it was a decent-looking hard-backed book, which people don’t usually leave lying on a wet pavement on a rainy day. She was trying to assess the book, and the whole situation: how did it get there?

Immensely relieved, I got there in time to claim my book and to explain in a few words what had happened. ‘Oh, it’s your book, is it?’ — she said, and handed the book back to me with a faint smile. The cover of the book was damp, but it was otherwise undamaged. The spine and the binding were still intact. It says a great deal about how sturdily such books were put together in those days.

When I returned upstairs with the book, my three-year-old brother’s giggle was triumphant. But just a year or two later, when he was capable of walking reasonably briskly and accompanying us on public transport, we witnessed a very different face of his self-confidence.

My father and I were going somewhere together, and my brother accompanied us. We took the tram from Rasbihari Avenue. My brother fancied the idea of sitting by himself on one of those benches where two seats were available and two people could sit together. We let him do that. At some point a memsahib boarded the tram. In that period this was a rare occurrence, but not impossible. Memsahibs used to be far more visible in Calcutta before August 1947. For instance, they could be seen walking with their teenaged sons along Park Street. Both mothers and sons used to wear long white cotton gloves up to their elbows, and the sons would put their arms around their mothers in a special position, as if protecting them. ‘See, how the sons look after their mothers,’ my father had once commented.

To return to the story of our tram journey, the memsahib, spotting the empty seat next to my brother, decided to plonk herself there. My brother stole a glance at his neighbour and burst into tears. He had never seen a white-skinned person in such close proximity to him before. We tried to console him, assuring him that nothing terrible was about to happen. My father explained to the lady that his son had not seen a white person in such close proximity before. ‘I am not going to hurt you,’ the woman assured the terrified child. The incident does tell us a great deal about how little children may well react to unexpected physical appearances. My brother had never seen so much white skin so close to him before: face, neck, arms, legs, everything pertaining to this stranger was strange to him. He might well have wondered if she was a real human being, or a strange new creature, an alien he had never encountered before. Even if he had seen any pictures of such people in books, seeing a real person with a strange appearance can be an unnerving experience for kids. Many a time in England, travelling on the bus, I have encountered the fixed stares of youngsters, usually little girls, sussing me up. When this happens, I invariably try to allay their fears by engaging them in some conversation. Sometimes a little girl will snuggle up to her mother when this happens, and hide her face in her mum’s bosom for a little while, but keep an eye on me, casting furtive glances at me from time to time, checking if I was still looking at her. This game of hide and seek can go on for some time, but usually most kids come round to a recognition of the stranger’s humanity and eventually bequeath on her a wise little smile. When this happens, you know that you have won.

I have sometimes wondered why little boys tend not to play this game of hide and seek on public transport as often as little girls seem to do. I suspect it could be because a boy’s ego does not permit him to admit in public that there is somebody a little unusual in front of him, a stranger whose looks he does not fully comprehend.

I do remember how, as a teenager in Calcutta, I used to be profoundly intrigued by the women draped in burquas (borkha in Bengali) who occasionally boarded buses. Two such figures would usually travel together. I knew about the custom, but nevertheless such apparitions were compellingly enigmatic.

Curiously also, though borkha is an established word in Bengali, I don’t find the word hijab in my Bengali dictionaries from Calcutta. I never saw a woman wearing a hijab when growing up in India. The word entered my consciousness in relatively recent times, in the context of reports in the British media and my association with social anthropologists. It was in London that I finally saw women wearing the hijab for real. A scarf to keep the head warm in cold weather was not new to me at all. Many women of my generation did that, and so, we noted with satisfaction in our student days, did the British Queen, but what could be the rationale for tying a scarf in that fashion, and covering the neck to boot, on a hot, stuffy summer’s day? Surely that would be dreadfully itchy and uncomfortable? It would also crush and ruin one’s dangling earrings.

Let me get back to my special interest in geography, which became a doorway to science for me. Besides Dudley Stamp’s classic book, I had another geography textbook entitled India, the Empire, and the World, the title of which indicates the pride that the British took in their imperial territories as also the special place occupied by India within that expanse. I think it might have been from this book that I acquired bits and pieces of information about where pianos were manufactured, which in turn made place-names like Leipzig, Stuttgart, and Dresden almost magical to me. As a school kid, I didn’t really have a clear idea about what had happened to such cities in the Second World War. Many years later, passing through Leipzig, I pestered people in a pub at lunch-time with the question whether such places in Germany had been able to revive their manufacture of pianos. Those I spoke to were mildly amused by my odd obsession.

Yes, I have written in several places in both Bengali and English about my passion for geography, which was one of my few windows to science. Very little science was taught at my school in my time, and that situation was not uncommon in girls’ schools in that period. A little later things changed, of course. The main problem in my time, I guess, was finding the right female staff and funding them. When I was in Class VI, there was a ceremonial boiling of water in a large pot to demonstrate the phenomenon of evaporation. The water was boiled until the pot was completely dry. On another occasion a mango stone was given a ceremonial burial under the ground and after some days or weeks dug out to reveal how it was growing shoots. They were most marvellous events, managed by the teachers of the junior school with some panache. But there was little else.

I had a book entitled Elementary Physiology by Bhatia and Suri, which I read with great interest, and looked dutifully at the illustrations and diagrams in it, but I just do not recollect who, if anybody, taught it to us, or indeed if it was a part of our school syllabus. Was it perhaps something pertinent to my Intermediate course at Lady Brabourne College or even my Philosophy Pass course at Presidency College? I am not sure. But it was an incredibly detailed and professionally written book. I found it very informative indeed. At one point it talked about reproductive organs and assured us that we would learn about such things when we were older — apparently we were not ready for such knowledge yet.

My father was conscious of the gap in my science education and asked me to read a certain section of a book he had. That section also ended by hinting that more information would come to us in due course when we were a little older.

In this connection let me mention another curious incident which perplexed me. In my textbook of English history someone was referred to as an ‘illegitimate son’ of somebody else, and I could make no sense of the expression. I looked up the polysyllabic word in the dictionary. It just gave the meaning as ‘illegal’, which made no sense whatsoever in the context. How on earth could anyone be someone’s ‘illegal son’?

I then took my query to my father. He said that ‘illegitimate’ meant ‘illegal’, but did not elaborate any further, so I was none the wiser. A little later, when I was in another room, I overheard my father saying to my mother that I had asked him the meaning of the expression ‘illegitimate son’ and he didn’t know how to explain it to me. I began to connect such inexplicable expressions so that I could grasp the reality behind them. All those goings on in the Ramayan and the Mahabharat, for instance. All those bizarre births.

When I was ten, I was bought a collection of Bankimchandra’s novels, which presented similar problems. Certain areas of reality were never quite clarified: they remained hazy. And interestingly, though it was OK for me to read Bankimchandra’s fiction, some of Sharatchandra’s novels were censored. Apparently, it was not all right for me to read them yet. Did my father think that Bankim’s ornate language cast an appropriate veil over certain troublesome facets of reality? I dare say that faced with the intractable aspects of our experiences, each generation reaches a compromise it can sensibly cope with. The fact is that when I was growing up, the concept of ‘sex education’ simply did not exist around me.

When it comes to different aspects of our education, there are simply too many memories to unpack. In the heydays of the Empire, there must have been a few genuine memsahibs who taught at our school from time to time — one would have to do some research to confirm this — but in my time I encountered only one. That must have been when I was about eight and a half or at most nine. The teacher read out Wordsworth’s poem ‘Written in March’ with much feeling, then asked us to paint a picture on the basis of what we had heard. I tried to do that as best as I could.

It actually became a very Bengali landscape — what else could I do? I hadn’t been exposed to any other landscape yet. I depicted the country as totally flat and green up to the horizon, with a stream winding in the middle of the visual field. There were thatched cottages, a man ploughing his field, and to crown it all, two palm trees crossing each other against the horizon, without which my picture would simply not have been complete to me.

The teacher was ecstatic. She held the picture up for all the class to see. She did not point out the fact that palm trees do not actually grow in Wordsworth’s Lake District. I think she was a very sensible teacher, understanding where I was coming from. I was simply depicting what the poem had evoked in me. I didn’t know that palm trees didn’t grow in that poet’s country, but I had realized that the poem evoked some sort of farmland — I had latched on to the image of the ploughboy — I knew what that was!

I believe at some point either she or another teacher of English, who was not a memsahib, also recited to us, with deep feeling, Browning’s poem on being in England in the month of April. Sadly from the perspective of cultural dialogue, most memsahib teachers left India after our Independence. Some returned to their homeland; others went to work in Australia.

As I have mentioned, my mother was disappointed that I could not become a singer. But what about learning an instrument? In those days my school, which both my younger sisters also attended, offered tuition in the violin and the piano. Yes, we were still within the orbit of the old Empire; there was no quick escape from that. But anyway the fact is that all my life, and especially as a writer, I have been mediating between climates, landscapes, environments, cultures. And I have done this in both the languages in which I write. This has been an essential part of the way I view things and write them down. It was a natural development of my relationship to geography, which had become one of my favourite subjects and my window to science.

In our school the piano was taught by a Parsi lady. The violin was taught by Mrs Bijoli Biswas, who was also our main English teacher in the senior school. Having lessons in such musical instruments was not really feasible for me. The piano was out of the question. Even learning to play on the violin was not really feasible. Even apart from the extra tuition fees, buying and maintaining a violin in the tropical climate were special responsibilities. Travelling with it on crowded public transport would raise further issues. Those girls in our school who had violin lessons came to school by car. At that time my father did not have a car. My parents were simply not in a position to cope with such extra responsibilities in that era. Robert, of course, growing up in Yorkshire, did learn to play on the piano, but was not encouraged to make music itself his main occupation. It was feared that such a life-style would not be economically viable — playing on the piano would be OK as a hobby, but not as a career. I made sure that Igor, our younger son, learned to play on the violin. When he was growing up, an excellent system was in place for the musical education of children in Britain. It was possible for us to benefit from this. Apart from the initial purchase of a violin, and insurance for it, there was no other major expense in that connection.

I realize that that is his life, not mine, and I am supposed to be writing about my own memories, but deep within me I realize that I very much wanted that at least one of my own children should learn to play a musical instrument to a reasonable level, and I have managed to achieve that goal. I have been happy for him when he has been able to play in various orchestras in Oxfordshire, and in the Imperial College Symphony Orchestra in London when he was a student at that institution. I am so happy that he still plays in a local Oxfordshire orchestra, directed by a music teacher he knows from his own school-days.

This exercise of writing down my memories has enabled me to be in constant touch with my essential self and deepest preoccupations. I have always felt sad that the pursuit of the arts is hedged in by so many difficulties in most societies, so often regarded as fine enough as a hobby, but problematic as a ‘career’. A ‘full-time career’ is expected to bring in substantial amounts of money: money for all one’s earthly needs and for extra display on top of that. Only when you earn lots of ‘dosh’ from any activity are you regarded as a professional in it — otherwise you are classed as an amateur. This way of looking at things does affect one’s relationship with the pursuit of the arts. Ironically, the word amateur does etymologically mean ‘one who loves, a lover’, and strictly speaking, that is precisely what one should be in one’s relationship with the arts. One should be an amateur or lover of the arts. But the meaning of the word has been allowed to become degraded and the word ‘professional’ has been elevated and allowed to supersede it.

In my life I have done what I can to rebel against this attitude. People expected me to become a full-time academic. When in the late 1970s after completing my doctorate, I found it well-nigh impossible to get a suitable academic job in England in my subject, I happily allowed myself to slide towards the life of a woman earning very modest sums of money while writing very energetically.

And I have done my best to encourage Robert to keep playing the piano, and Igor to keep playing the violin, for the sake of music, for love of music and nothing else. I encouraged our elder son, Virgil, to sing in a choir and to act when he was at school. We remember his very spirited portrayal of the Shakespearean character of Caliban when he was at school. His professional and academic qualifications are in Book-binding and Graphic Design, and I have encouraged him to draw and paint for the sake of art, out of love for art. Art or music may not be your main money-earning job, but if you have some skills in it, just go ahead and do it. The world will be a better place if you persist in your love.

Robert’s Bechstein manufactured in 1908,

refurbished twice. This is 2014And amazing things can happen to people in life, contrary to expectations and nuggets of received wisdom. There was a South Indian Christian girl in my class at school, who, at some point, was struggling with her class work in mathematics. Teachers who trusted me asked me to assess why she was in that predicament — could I perhaps help her in some way? I never told the teachers about my childhood doubts as to whether 3+5 could be the same as 5+3. I just sat with the girl in question over a few afternoons and tried to find out what the problem was. Now, if she had been a South Indian who spoke no Bengali at all, we might have had some problems in communication. But that was not the case at all. She had grown up in ‘Cal.’, as many non-Bengalis attached to the city affectionately called it even in the mid-1980s. And she spoke Bengali fluently. So yes, I sat with her over a few afternoons and tried to help her with her work in mathematics. To my amazement, she eventually went on, to become, a fully qualified science teacher at our school.

When I was assessed for entering the Diocesan School, presumably a little before the age of eight, I was deemed fit to enter a class with girls two years senior to me, but there was a comment that I was ‘very weak in English’. Why? Because I had got the spelling of one word wrong somewhere. English, of course, was not even my first language! I have no idea how that poor girl, so weak in English, eventually obtained the highest marks in English in her Intermediate Arts exam even before reaching her sixteenth birthday and was admitted to read English Honours at Presidency College.

English, of course, has been, and continues to be, an object of fetishistic attachment in India. Some people seem to think that one cannot be considered a serious writer, a writer worthy of attention, unless one writes all or almost all one’s books in what has attained the status of a contemporary deva-bhasha or ‘language of the gods’. Some people who claim to admire my writings lament that I do not write more in English. I point out that I have indeed written books in English which have received international recognition — indeed one such book, scholarly in its scope, is currently being translated into Spanish in one part of the world and into Chinese in another. But I haven’t written any of my novels in English, have I? I have written all my novels in Bengali. Tut tut. How can anyone be regarded as a serious writer if he or she has not written a novel in English? I have published five collections of essays and reviews in Bengali, but though I have written quite a few such pieces in English also, I have not gathered them together and published them formally as a separate book. I have simply not had the time or energy to locate a suitable publisher or publishing platform. I have been continuously busy. Every article and paper I have written in English has of course been published somewhere — either in a journal or in a scholarly book.

But I am supposed to be writing more about my childhood, not so much about contemporary predicaments. And thinking about it, there has always been an incredible paradox in the attitude to education prevailing everywhere. On the one hand, when growing up, I was not aware of a general system of compulsory state-supported schooling around me. In that period no one seemed to care whether the children of the working classes were receiving schooling or not. There was no special concern about the widespread illiteracy that prevailed — indeed it might have been tacitly condoned because illiterate workers could be exploited more effectively. But the working classes, even if they were illiterate, were certainly not innumerate! If they had been innumerate, they simply could not have survived. Indeed, they tended to be very good at mental arithmetic.

At the other end of the spectrum there was an inordinate attachment to the importance of English as a criterion of education. After I was offered a place at the Diocesan School, some people suggested to my parents that the Diocesan was not good enough. To learn English really well, which many people regarded as of utmost importance in one’s educational status, one had to attend the school known as La Martiniere. There was one for boys and one for girls. So off I went to be interviewed at that prestigious institution, the one specifically designed for girls. The top lady there was not a Bengali Christian as at the Diocesan School. I cannot recall if she was a pucca memsahib or an Anglo-Indian. One question she asked me was about bees — what did bees do? I did not know how to give an answer to this question in English. I lifted my arms and flapped my hands to indicate a bee’s flying motion. Afterwards, the lady told my father that she had been deeply touched and impressed by my attempt to answer this question. She offered me a place in her school. It would have been quite a bit more expensive to send me to this school than to St John’s Diocesan Girls’ High School. And if I was sent there, my sister Karabi would have to be sent there too. In the end my parents decided against sending me to La Martiniere. They reckoned that it was not worth the extra expense. I could learn English just as well at the Diocesan School, whereas I might become ‘Anglified’ at the other school and not learn enough about my own country and culture.

Attending St John’s Diocesan Girls’ High School, I was automatically exposed to a large measure of India’s cultural diversity. Bengalis — not only Hindu Bengalis, but also Muslim and Christian Bengalis — were in every class. There were Jain Gujaratis and Urdu-speaking Muslims in my class, and I have already mentioned the Christian girl of South Indian ethnicity who was in my class.

Let me mention some of the teachers in my school. The Principal, Miss Charu Dass, was regarded as a formidable lady. She wore the sari with the anchal in front, ‘up country’ fashion. It was always an immaculately white sari with a slim border — usually blue, as far as I recall. Although regarded as formidable, she was by no means an unkind lady. It is just that the maintenance of the discipline of the entire school was her responsibility. Every morning she conducted an assembly, where she read a short prayer, to which no one could object. After India became a republic, it was officially a ‘secular’ country. As I now realize, the school could not afford to antagonize any group of parents: it was not a state school, but one with links to a mission society, run by Protestants. It had to tread carefully. When I started school, the fee was modest — as far as I can remember, ten rupees a month. But inflation soon saw it go up significantly. The motto of the school was ‘The good retain, the better follow’.

School Prize 1950 School Prize 1950, signed by the Principal, C Dass The school did maintain a Protestant chapel which was attended not by the day girls but by the boarders. My sister Karabi had to live in the school hostel for a brief period when my father was posted outside Calcutta. The school food was not good at all. I occasionally had to lunch there and knew from direct experience how poor it was. It could have been plain and simple Bengali food, without frills, but it wasn’t. I found it almost inedible. I have no idea why it was allowed to get so bad. So when my sister had to stay at the school hostel, for a while, I used to take some sandesh for her whenever I visited her at weekends. I was then studying at Presidency College and staying with my relatives at Palit Street which connected Lansdowne Road with Ritchie Road. I had to take a bus from Ritchie Road to get to the junction of Harrison Road and College Street. So yes, I would buy a packet of sandesh for my sister at Mrityunjay Mishtanna Bhandar, then get a bus from Lansdowne Road to proceed to the school.

After Charu Dass retired, Molina Mukherjee became the Principal. Other teachers I remember well from the senior classes are Bijoli Biswas who taught us English, Romola Biswas who taught us mathematics, Miss Pyne who taught us Sanskrit, Miss Varki who taught us Geography, and Reba-di, who taught us drawing and painting — what was her maiden surname in those days, before she married the artist Somenath Hore and herself became the well-known artist Reba Hore? It must have been at her recommendation that I used to be entered by the school for the annual competitions of the Royal Drawing Society of South Kensington, from which I got certificates, with special praise for my work, and once even a special prize, which happened to be an illustrated hard-back book on the French artist Chardin. Reba-di was disappointed that I did not go to art college and become a painter.

I must say that my father encouraged me in my pursuit of the visual arts, buying me paint-boxes from G. C. Laha’s well-known shop, taking me to the annual exhibitions of the Academy of Fine Arts, where I would eye the famous Lady Ranoo Mookerjee from a distance, and thanks to which, names like Amrita Sher-Gil and Sheila Auden became inscribed on my consciousness at an early age. Years later that childhood interest in art bore fruit in the substantial research project which I undertook, along with other colleagues, on the impact of Tagore’s protanopic colour vision on his writings and visual art.

My painting Dissipation that hung in the house of my mother’s brother (K K Dasgupta) at 11 Camac Street. This was recently scanned for me by my cousin Urbashi Barat (nee Dasgupta).

When I was in my final year at school, there was a reproduction of a Van Gogh painting in the classroom. I liked the colours in it. From various books I gathered bits and pieces of information about visual art. I became familiar with names like Monet and Manet, and myself did water colours depicting women with umbrellas walking in rain-drenched streets.

Following a similar thread, I would also like to make a special reference to the Geography teacher, the Malayali Miss Varki. I was very fond of this school subject, Geography, and I used to get high marks in the exams conducted by Miss Varki in this area. My attachment to the subject known as Geography was not mundane, but overwhelmingly romantic. I simply loved it. It told me about climates, climatic regions, the natural vegetation and agricultural products of these regions, the ocean currents and their effects on climate. This school subject became my personal doorway to science. I loved drawing maps and indicating what grew where. The tundra — how I loved drawing this when I drew a map! The Gulf Stream that carried warm waters to the British Isles and the winds that carried the monsoon to India absolutely fascinated me. I also had a special book on Eskimos, how they survived in their unfriendly environment and made the most of that challenge. I also had a red booklet which I cherished, entitled Calcutta, The City of Palaces. Years later, all these interests gelled to build my awareness of climate change, which I incorporated as a major issue in the first play I wrote.

When I was a student at Oxford in the 1960s, another student who was formally studying aspects of geography once asked me: ‘Don’t the vagaries of our English weather — now sun, now rain, now warm, now chilly, now blue skies, now clouds — bother you?’ ‘Not at all,’ I said with confidence, ‘I was prepared for these fluctuations. I knew, from the geography I did at school, that this was a feature of the cool temperate oceanic climate.’

The guy who had asked me the question could hardly believe what he heard. Here was a student of Eng. Lit. from India who knew the jargon of his own discipline!

But my attachment to geography was truly deep. I could not erase from my mind a photo in one of my textbooks which showed a forest in the North American west coast region, where a very tall tree grew. There was a photo of the immensely thick and sturdy trunk of this tree in one of my books, through the bottom part of which a passage-way had been cut, and in that passage-way stood a car with a driver, indicating that there was a viable route through that gap in the tree. To me this photo incarnated the sheer magic of geographical knowledge.

I was still under ten when Miss Varki introduced us to the distant continent of South America, to the enchantment of names like Rio de Janeiro. Rio de la Plata, and Tierra del Fuego. Some of the magic, I now realize, was not just the magic of knowledge: it was also sheer verbal magic, the resonance of language itself. Miss Varki must have started teaching our class from January 1950, when I was nine and a half. The magic of those names from South America was simply irresistible to me. Years later, when standing on the balcony of the villa Miralrio, I gazed at the estuary of the Plata, I felt an indescribable thrill. So this was the view that Tagore had from this balcony, and Victoria Ocampo was so right, this was a view so worthy of his attention. When I was there in 1985, the sandbanks had moved away much further since the time when Tagore had seen it in 1924, but it was still a magnificent sight, with the sun shining on the sailing boats in the estuary in the distance.

I have mentioned several times that we did not have a radio set in my early childhood. My father thought that listening to the radio would distract us children from doing our homework and serious studies. News could be read in the newspapers. All throughout our days in the Rasbihari Avenue apartment, we used to listen to sound waves from other people’s radio sets wafting on to our ears. Especially in the run-up to Durga Puja, the Mahalaya chanting came to our ears in that fashion. Finally, when I was in my early teens, and we were living in an apartment on Lake Terrace, my father relented and bought a radio set. We could listen at last to ‘Anurodher Asor’, the programme for songs requested by members of the public. This programme was of special interest to my sister Karabi. She had long been interested in popular songs from Hindi films and had accumulated some 78 r.p.m. records of such songs, including hit songs from the popular film Anarkali.

After we acquired a radio set, I listened from time to time to BBC’s Radio 3. I heard Verdi’s opera Aida — must have been just extracts. When I came to Oxford and noted that Aida was going to be performed in the principal theatrical venue there, I decided that I simply had to experience this. I didn’t have the courage to go alone. Two Welsh girls who were students of occupational therapy and lived as lodgers in the same house as myself, under the same landlady, offered to accompany me. But they didn’t have enough money to buy proper tickets. Nor would they let me buy tickets for them. They opted for standing in the topmost upstairs gallery for a token pittance, so I had to do the same. We stood for three hours in the upstairs gallery, leaning on a railing, our backs to a wall. That was quite an experience. Since then I have loved opera, and also ballet, as special art-forms of the West. But tickets for performances are so expensive that one can experience stage shows only a few times. Unless, that is, one belongs to the rich set. In the past the non-rich had to rely on long-playing records and on the radio and television. So it was for me.

I swap clothes with one of my Welsh friends

outside Iffley Road lodgingsI would not like to take leave of my Welsh friends without remembering that one afternoon in my first year at Oxford they banged on my door very loudly and announced: ‘You said you had never seen snow. It is snowing now. Snow is falling from the sky. You must see it.’

They rushed me downstairs. What a sight awaited my eyes! The sky seemed to have come down lower than usual. It felt closer to our eyelids. And the white flakes were falling from the sky without making any noise. So different from the lashing of rain! The pavement was getting white. What a special sensory experience that was!

As luck would have it, as a student in my third year at Oxford, I witnessed the famous winter of 1962-63, supposed to be the coldest or at least one of the coldest British winters of the twentieth century. Yes, it was an extraordinary experience, which I tried to portray in a Bengali poem. In those days I did not write poems in English, and I was interested in capturing the mood of that extraordinary season in a language that had evolved in the tropics. The contrast between the medium and the message was the special challenge that interested me. Meanwhile in daily life I had to obtain special permission from the university authorities to attend lectures and tutorials in trousers. In those days girl students at Oxford could not attend lectures and tutorials in trousers. I was given special permission as a foreigner not used to such extreme climatic conditions. Well, in very cold weather I used to secretly wear trousers under my sari anyway. Nobody could see my trousers from the outside. But in that winter of 1962-63 the conditions became so extreme, with piles of snow and ice on the pavements, that it became impossible to manage trousers and sari together. My fellow students who were ‘natives’, born in a cold country, made jealous noises at the privilege granted to me — they had to wear skirts or knee-length frocks at lectures and tutorials, no matter how cold it was. Indeed in my time girls were not permitted to wear trousers in the college dining-room. They retaliated by arriving in trousers and then changing to skirts right at the door of the dining-room, making the costume change in public. They did of course wear stockings with suspender belts, or waist-high tights. I took one look at the suspender belt method for holding up one’s stockings and decided that it was not for me. Waist-high tights were better for me. In those days all the colleges at Oxford were single-sex institutions, either for boys or for girls. All colleges operated as residential institutions, and none of them were mixed.

There was a huge sensation in my college in (I think) the academic year 1961-62 when a female ‘scout’, that is to say, an attendant who cleaned rooms, found a boy in bed with a girl. The poor things had forgotten to secure the door. The boy was ‘rusticated’ from his own college for a limited period, but the girl was actually ‘sent down’, that is to say, she lost her place at the College and at Oxford University. It is hard for us to believe that now. But that was the official (and very hypocritical) morality of those days.

§From when I was about nine, my father channelled a great deal of his energies in giving me extra tuition in subjects which would not be covered by the school. He was happy that I would start Sanskrit at school from Class VII onwards: he was immensely relieved that the school would take care of that, because neither he nor my mother could have given me lessons in Sanskrit. But he did what he could to give me extra support in that subject-area. He bought me the collected works of Kalidasa, a play by Bhavabhuti, and a play by Shudraka. All the books carried some integrated critical apparatus, so I could plough through them and make some sense of the texts. I had just started my Intermediate Arts course at Lady Brabourne College at the age of fourteen, when Kalidasa’s great play, the Abhijnanashakuntala, not a part of my course yet, burst upon my consciousness. I just had to write something about it, which I did, and submitted it to the college magazine. The teachers of Sanskrit at the college were surprised when they found out that the girl who had written the article was just in her first year at college and was not a student of Sanskrit Honours at all. They wanted to see me and with some trepidation I went to the staff common room. They said they liked my essay, and as far as I can remember, it was published in the college magazine.

Perhaps because of this incident, the teachers of Sanskrit at Lady Brabourne College, where I spent two years doing my Intermediate Arts, acquired some confidence in me and involved me in activities relating to their subject-area. I entered a recitation competition in Sanskrit and won a prize, reciting lines from the Kumarasambhava describing Gauri’s penance to win Shiva. I acted in a Sanskrit play, playing the role of Duryodhana. I think the play was Pratima-nataka by Bhasa. Lady Brabourne was a college for girls only, so girls had to play both male and female roles. Our rehearsals were often supervised by the Sanskrit scholar Sukumari Bhattacharjee. I loved my role, ranting and stomping all over the stage in my warrior’s gear and enjoying every minute of it. Sanskrit scholars invited by the Principal of the College for the final show or shows sat in the front row of the audience and applauded my performance. I believe I received a prize for this also!

A note on my memory of Sukumari-di would not be inappropriate here. She was one of those rare academics who had the necessary formal qualifications to teach both Sanskrit and English at university level. She was at that time in the English Department of Lady Brabourne College, but she regularly advised us on how to act in a Sanskrit play. She showed us how to do the preliminary ritual called danda-puja. Sukumari-di was married to Amal Bhattacharjee, who taught English at Presidency College. I am one of those lucky students who have been taught by both Sukumari-di and Amal-babu. I have also been privileged to receive a visit from Sukumari-di here at Oxford. It was well known that Sukumari-di had had an initial problem in studying Sanskrit at a formal level. She came from a Bengali Christian family. The story goes that a Sanskrit scholar under whose supervision she had been keen to study had said that he would not ‘give the Vedas to a mlechchha’s ears’. She is reported to have retorted: ‘Who gave the Vedas to Max Mueller’s ears?’, Max Mueller being of course the noted Sanskritist of German origin from the 19th century. A ‘mlechchha’ is a non-Hindu, someone outside the formal caste-ordered Hindu social system. There is a clear parallel between most orthodoxies when it comes to thinking about who is in and who is out, who is an insider and who is an outsider. At Oxford I met Christians who considered that a pagan could never be equal to a Christian. In India likewise there must have been men who considered non-Hindus to be inferior to Hindus, but in my growing years I did not meet such characters. After India became a secular state and the Indian constitution formally declared its commitment to ‘no discrimination’ against any group on religious grounds, fundamentalism tended to become muted, not articulated. And that was the dominant ambience in which I grew up. It was regarded as unacceptable to hold prejudiced views against any group on the grounds of race, sex, caste or creed.

In due course, I read Sanskrit at B.A. Pass level when I read English Honours at Presidency College. My father insisted that though I would be specializing in English Literature, I must retain Sanskrit as a subsidiary subject, because the knowledge of Sanskrit would be an asset to me if I wanted to pursue serious writing in Bengali. How right he was, and all my life I have been grateful to him for this advice.

At Presidency College, we went across the road to Sanskrit College for our Sanskrit classes, and were taught by scholars eminent in their fields. We read Abhijnanashakuntala line by line with Govindagopal Mukhopadhyay.

When I came to Oxford in 1960, my knowledge of Sanskrit was treated by my tutors with utmost respect. Miss Sisam, who taught us Anglo-Saxon, medieval English, and the history of the English language, would check the etymology of this or that word with me, trying to find out if a cognate word existed in Sanskrit. Miss Elliott, who taught us Renaissance literature, decided to read Virgil’s pastoral poetry with me and just plunged me into the Latin text, like my father used to do with French and German. I could look at the translations provided in the Loeb classics edition. A line still haunts my mind — I hope I remember it right — it is about the preparation of food, about pounding garlic and thyme together in oil, presumably olive oil — ‘alia serpullumque herbas contundit olentis’. Well, they still make sauces and salad dressings like that in the Mediterranean countries, and in the course of my life in England, I learned to make them too!

But I am rushing in a ‘fast forward’ direction again. I was talking about my father’s plans to diversify my education in languages and literatures. When I was about eight or nine, he started giving me lessons in French himself and borrowed records of French songs from the Alliance Francaise de Calcutta. In those days the Jesuits Father Antoine and Father Fallon, associated with St Xavier’s College, used to give free lessons in French and read French literature with those who were interested in such things. My father accompanied me to such classes. He also took me to the performances of one or two French plays at St Xavier’s College. This early initiation into French helped me to teach myself to read Spanish at a later stage in my life and paved the way to my researches on Victoria Ocampo.

After I made some progress in French, my father started giving me German lessons. I found German much harder to deal with, mainly, I suspect, because of what I perceived to be a kind of mismatch between the sonic aspect of the language and the script in which it was written down. I wonder now: did my father ask me to read chunks of German text in the Gothic script? There certainly were a few books printed in Gothic in his collection. I read the lyrics of Goethe and Heine with him and ploughed through Goethe’s novel Die Wahlverwandschaften or Elective Affinities in the original German. I still remember the exclamation ‘Du liebst mir, Ottilie!’ from that reading. Although I found it difficult to wade into, I was, later on, thankful for my introduction to the German language because it was very relevant and useful when I had to do Anglo-Saxon at Oxford. Old English and Old German are related languages and both belong, of course, to the Indo-European family of languages. I eventually translated some Anglo-Saxon poems into Bengali, keeping the alliterative, half-line format as far as possible. I was then grateful for my early initiation into the Germanic mode, and also thankful for my grounding in Sanskrit, which gave me access to synonyms in Bengali with the same initial sound.

It is not possible to think historically if one does not make connections between the past, the present, and the future. Just as French helped me, via Spanish, to move towards Victoria Ocampo, so German, besides helping me in my Anglo-Saxon, was very useful when I toured Germany in search of clues to Rabindranath Tagore’s attraction to Primitivistic and Expressionistic art. My research colleague Sushobhan Adhikary and I looked at museums and art galleries in 18 German cities in search of clues as to what kind of art might have appealed to and influenced Rabindranath Tagore. I was given a travel grant by the German Academic Exchange (DAAD) to enable me to undertake this art tour, and our friend from Santiniketan, the German scholar Martin Kaempchen, introduced us to a network of friends who could help us in our journey. Once the book was ready for the press DAAD also helped with the cost of printing the colour plates for the big book, Ronger Rabindranath, that came out of this project on Tagore and his colours. Wherever we went in Germany in connection with this project, we were struck by the genuine desire of German academics and art-related institutions to assist a genuine research project. Their support of what they perceived to be a cultural and scholarly project of some significance was, without a doubt, exemplary. I really believe that countries have to remain in contact with their neighbours and collaborate with each other for their common good as and when necessary. The attitude of those British people who want to distance themselves from Europe is incomprehensible to me. More than incomprehensible; I think it is a folly.

There were substantial ripples on India’s political horizon when I was a student at Lady Brabourne College, especially in India’s relationship with other countries. India wanted international friends. I remember going to an exhibition on China at the college. We heard the phrase ‘Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai’, that is to say, ‘the Indians and the Chinese are brothers’. But the Chinese did not seem so keen to promote this brotherhood at the time. India then supported an alliance with Russia with some vigour. In November 1955 I went to a vast public meeting with my parents in the Maidan in Calcutta. It was a monumental political rally to welcome Bulganin and Khruschev to our city. Wherever one looked, one saw a sea of faces. It was an unforgettable occasion.

After Lady Brabourne College I went to Presidency College to study English Honours, where we were taught by excellent teachers in every department we had to deal with. In my own time there the teachers were all men. The first female teacher was recruited after I left. In this respect the College was in a half-way house in those days. No female teachers, and girls were accepted as students only in the B. A. and B. Sc. courses and the College’s own affiliated M. A. classes. They were not accepted in the Intermediate Arts or Science classes. In my time there was a dedicated Common Room for girls. One of my female cousins a little older than me says that she was the first or one of the first female students to be accepted at Presidency College. A very small room was apparently rigged out for her use in lieu of a proper Common Room, so that she could sit down in between the classes she had to attend.

Presidency College was famous for its debates, which were held in the Physics Lecture Theatre. I remember hearing Amlan Datta there. In those days I never dreamt that one day I would consider him an honoured friend. I also recall a programme in that room, in which I had to recite one of my own poems, and had the privilege of having the poet Sudhindranath Datta in the audience. He was sitting in the front row, and after I read my poem, he smiled and clapped enthusiastically. Needless to say that it made my day.

At Presidency College I was in charge of a ‘wall magazine’ which was behind glass and kept under lock and key. One of my editorials there, ‘Bitorko na Prahasan?’ (Debate or Farce?) was much appreciated by some of the teachers in the Bengali Department, and I was asked to come to the Senior Common Room where I was complimented.

The teachers of English were a great team, with Subodhchandra Sengupta as the Head of Department. The others included Tarapada Mukhopadhyay who taught us Macbeth, the legendary Taraknath Sen who taught us King Lear, Amal Bhattacharjee, whose teaching of Keats’s Ode to a Nightingale I vividly remember to this day, Sailen Sen, who taught us aspects of the English language, and another person — did we call him Phani-babu? — who taught us a text of Edmund Burke. The Principal of the College was (I think) a British guy, who also taught us a paper on philology and the history of the English language. We followed a book by Otto Jespersen, which I believe is still lurking somewhere in my house.

Of course, it was an elite education. No doubt about that. After I did well in my B.A. Honours examination, I went to see Taraknath Sen in his famous library cubicle where he usually sat and took his classes. He said to me: ‘Ask your father to send you to Oxford; that is where you need to go now; there is not much else we can teach you here.’

‘Sir,’ I replied, ‘my father cannot send me to Oxford just like that. He has three other children. I need to win a scholarship to study at Oxford.’

The other teachers in the other departments who taught us for our various Pass (i.e., subsidiary) subjects were equally dedicated academics. I obtained the highest marks in our compulsory Bengali paper at the final exam, obtaining an award named after the novelist Bankimchandra Chatterjee. Sanskrit, as I have already indicated, was taught at Sanskrit College across the road.

At Presidency College I belonged to a group of five girls who often frequented a place for snacks on College Street itself, or the famous Coffee House on Bankim Chatterjee Street, facing Sanskrit College. Three of us, Shanta Sengupta, Basanti Ganguly, and Basanti Bhaduri, were reading Bengali Honours, and the other two, Esha Mukhopadhyay and myself, were reading English. We sometimes referred to ourselves as the ‘five Pandavas’. Of course, the Pandavas of our epic tradition were five men, not five women, but the gender difference was the least of our worries.

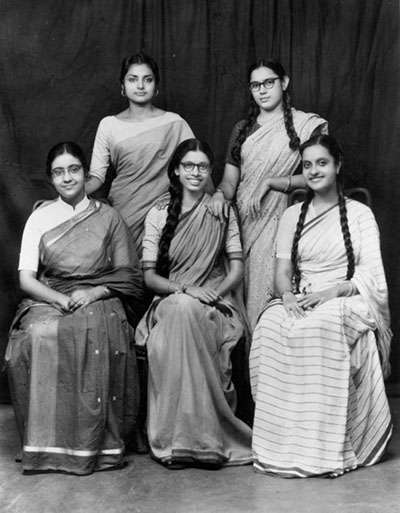

Me with Esha Mukhopadhyay, Shanta Sengupta, Basanti Bhaduri,

and Basanti Ganguli (left to right)Is there perhaps something compelling about the number five — something related to the five fingers of a hand — that makes the number attractive to members of a small group of friends? Because in my student days at Oxford too I belonged to a group of five students — Jon Wisenthal, Andrew Deacon, Leslie Holden, and Robert and myself — but there was nothing exclusive about the group at all and each of us had other friends with whom we interacted. Likewise, when we were in Brighton we were also members of a group of five for a short while. Besides Robert and myself, there was Manu Bhatia, who, like Robert, was doing research at Sussex University. Then Jishnu Dey, the son of the poet Bishnu Dey, came to do research at the same University and was accompanied by his wife Mira. We introduced Manu to Jishnu and Mira, and we were then a group of five. After returning to India, Manu met a sister of Mira, whom he eventually married.

Me with Robert, Leslie Holden, and Andrew Deacon

in Brighton in 1964 (left to right)To return to my Presidency College days, ‘us girls’ did not have a lot of pocket money to spare. We had to make sure we had enough for our bus fares. When it came to buying books, I was very lucky because I could spend the prize money from my Intermediate Arts exams. This money was earmarked for buying books, which I did at two of the big bookshops on College Street.

The little place for snacks on College Street had a strategy to stop us girls from stretching their slender resources. If they spied us approaching, they removed their full bottles of tomato ketchup from view. They clearly thought that we tended to use ketchup far too liberally.

At the Coffee House, which served excellent Mysore coffee, we developed a special strategy ourselves if by chance three of us went there together. The great attraction for us there was the dosa, a South Indian snack we did not get at home. These were fairly large, chunky snacks in those days. We would order three coffees and one dosa and ask for two extra plates. We would then cut the dosa into nine pieces. The central stuffed part would be divided into three pieces, so would each tail-end, and then with scrupulous fairness we would proceed to share out these nine pieces between us — three for each girl. The waiters never begrudged us the extra plates. They realized that we were cash-strapped. Occasionally one of us would buy an extra coffee right at the end as a good gesture. I often did that myself. The room was always thick with the smoke of cigarettes. Many of the students of our generation smoked recklessly — I mean, of course, the male students. In my time as a student at Presidency College, I never saw a female student smoking. But the fact that smoking was bad for our health was not yet a part of received wisdom in the fifties.

The first time I saw an Indian woman smoking in public was in London in the early sixties. It was Rajeshwari Datta, the widow of the poet Sudhindranath Datta. In those days Robert and I were based in Brighton. Brighton was on the door-step of Sussex University, where Robert was then doing his doctorate. I had been asked to translate some of Sudhindranath’s essays into English. Perhaps I had already begun the job. We travelled to London by train to meet Rajeshwari and discuss the project. The translations I did were eventually included in the book The World of Twilight, published by Oxford University Press, Calcutta.

Another journey we made from Brighton to London almost in a spirit of pilgrimage was to attend a concert where the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky was conducting the orchestra for the performance of some of his own music.

For some of the time when I was living in Brighton, I was of course teaching in London and commuting between the two cities three times a week. I was in charge of the ‘Bidesher Boi’ column in Desh and used to read on the train the books I would review. I also wrote some poems when living there which became very popular. Nari, Nogori was also basically put together there. In truth, the Brighton days were an important phase of my literary development.

Coming back to my strictly ‘undergraduate’ years at Presidency College, which were between 1956 and 1958, I vividly remember how, in some of the Philosophy Pass classes, I struggled to follow the windings of abstract thought. One of our teachers had an intriguing habit: he would look up at the ceiling-fan whirring above us and ask us to be aware of it. I would strive with all my might to reach the desired goal. When I thought that I had arrived at that point, I would hear him asking us to be aware of that awareness. Whenever I heard about this business of ‘awareness of awareness’, the focus of my attention tended to flicker and flutter uncontrollably, and I no longer knew in which direction I was meant to be going. My mind would be in a state of helpless wobble.

In Presidency College, conversations between male and female students happened in the corridors. Groups of students formed knots and discussed things standing, because boys and girls did not share a Common Room or a similar space. I remember talking in that fashion to Surajitkumar Dasgupta, a budding poet whom I persuaded to contribute to the college magazine when I became the editor. The editorship, held for a year, tended to go to the best arts graduate of the college for that year, when we were technically in our fifth year, studying for the M. A. degree. Surajitkumar was a very promising poet who, sadly, died prematurely. There are two poems by him in the magazine.

Indeed, several brilliant students of my time were persuaded by me to contribute to the magazine when I was the editor. All of them went on to achieve distinction in their careers. One big decision I took as the editor was to scrap the cover design that was being used year after year, suggesting ritualistic puja-style worship. To me it was incongruous, not fitting in with the secular education we were receiving. I got an arty person to do an abstract cover design for me, which was much appreciated by my contemporaries and many of our teachers too, who complimented me for the new cover. Sadly, the next editor, Gayatri Chakravorty (not Spivak yet!) must have been persuaded by a die-hard conservative member of the Senior Common Room to bring back the old cover suggesting a puja-style offering, so we were back to our worshipful days.

Presidency College Magazine when I was editor in 1958/9 Presidency College Magazine editors to 1958/9 Such a lot of our conversations between boys and girls in those days also took place right in front of the college gate, with us standing on the pavement — all because we had no Common Room where we could sit together. Or else we had to visit the Coffee House and spend some time and money in that smoke-filled room.

I remember having conversations in front of the college gate with a black African student who had come from his native country to acquire a university education in India. I don’t remember precisely which country he had come from, but I remember that he used to wear colourful robes.

In the early 1960s at Oxford a student from Ghana used to try to persuade me to come and work in his country, assuring me that I could earn lots and lots of money there! He was very sincere in this, and also had a great sense of humour. I learned from him the expression ‘sugar daddy’!

Among students with whom I used to carry on conversations, standing on the pavement outside the college gate, were Pranab Bardhan, studying Economics, and Ahin Choudhuri, initially studying History and then Law. Pranab eventually became a distinguished academic in California. He married Kalpana, also a contemporary of ours. Ahin, I believe, was just a little senior to me. We also overlapped a little in our time at Oxford. Ahin took an interest in poetry and became an admirer of my poems in the early sixties. In later years he and his wife Ajanta became good personal friends.

- Cover | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 (Last): Manipur Memories

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us