|

|

Making Connections: Hungry Hungarians meet Bengal Tigers

Ketaki Kushari Dyson

Related Articles:

Rabindranath Tagore and Hungarian Politics, by Imre Bangha

Gallery: Tagore in Hungary

Hungry Tiger/ Encounter between India and Central Europe: The Case of Hungarian and Bengali Literary Cultures

by Imre Bangha. Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, pp. 344. ISBN: 81-260-2583-2 Hungry Tiger/ Encounter between India and Central Europe: The Case of Hungarian and Bengali Literary Cultures

by Imre Bangha. Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, pp. 344. ISBN: 81-260-2583-2

It is now recognized

that one of the fallouts of the Saidian conceptualization of ‘Orientalism’ has

been a decline in the study of Oriental languages and literatures in Western

universities. This is not surprising. Why would young men and women spend seven,

eight, nine crucial years of their lives acquiring skills in a foreign language,

if it earns them the stigma of being collaborators in an imperialist project?

The decline of Arabic in American universities has apparently been particularly

noticeable. One could guess the situation when the Iraq war began

and media coverage indicated that American soldiers were going to the

battlefield without interpreters who could interpret for them. In one incident

American soldiers at a checkpoint fired on a vehicle with women and children

because none of them knew how to shout ‘Stop!’ in Arabic.

Fortunately for us,

the world, though supposedly shrunk into a global village, still has pockets and

reservoirs that resist hegemonic conceptualizations. The life and work of the

young Hungarian scholar Dr Imre Bangha constitute a shining example of such

resistance. I remember vividly my first meeting with him in Santiniketan in the

90s. The image I retain is that of a young man full of curiosity, generosity of

spirit, and human warmth, who expected to be accepted as a friend straight away,

no more, no less. I am happy to put it on record that we have never fallen out,

and let me from now on refer to him as Imre – I shall feel much more comfortable

if I call him that.

Imre was born in

Győr,

Hungary, and

obtained his MA in Indology and Hungarian from Eötvös Loránd

University, Budapest. He subsequently

gained a doctorate in Hindi from

Visva-Bharati

University and has since

then been a Lecturer in Hindi on a part-time basis at the Faculty of Oriental

Studies, University

of Oxford. For some time

now he has been dividing his time between

Oxford

and Miercurea in northern

Romania, where he has an attachment at the

Sapientia–Hungarian University of Transylvania. His knowledge of languages is

mind-boggling. Unlike most other foreign scholars who write on Indian subjects,

he wrote his doctoral dissertation at Visva-Bharati in Hindi itself: Ānandghan ke kabittő me upamāmūlak alamkārő kī yojnā (Simile-based

figures of speech in Anandghan’s quatrains). In addition to Modern Standard

Hindi, he knows the Braj dialect and has a basic knowledge of the Rajasthani and

Avadhi dialects as well. Not only does he have a formidable list of publications

in Hungarian, Hindi, and English, but he also has skills in Sanskrit, Bengali,

Urdu, Gujarati, Italian, French, and Spanish, and in addition some basic

knowledge of German, Latin, Oriya, Persian, Punjabi, Romanian, Russian, and

Telugu! In other words, in the Saidian scheme of things, he is poised to take

over the world, yet as far as I

know, his extraordinary gift in languages is not in the service of any secret

Central European plot to dominate either the Orient or the world at large.

Hungry Tiger

is a book for which some of us have been waiting for a long time. It was held up

in the press because of the inability of the printers to insert the right

diacritical marks in Hungarian names and terms; I am so very glad that I was

able to intervene and end the deadlock, and Sahitya Akademi allowed Imre to

insert the marks himself. Because of the book’s prolonged gestation it has the

distinction of having three titles: one on the cover, a slightly different one

on the title-page, and surprisingly, yet another one on the reverse of the

title-page. The one I have used at the head of this article is the one on the

cover, which reflects the author’s final decision. Regrettably, Sahitya Akademi

did not execute the change on the title-page, and as for the third variant on

the reverse of the title-page, I have no idea how the publisher managed that!

But anyway I am happy that the book is finally out, even if it has three

identities.

“I started to write

this book,” says Imre, “while a student in Budapest and my original motivation was a

fascination for literary interaction between two impossibly distant cultures. I

hope something of this original fascination can be retained when surveying the

richness and diversity of representation. In many cases the facts can speak for

themselves better than any theory about them.” Fascination is indeed the

key word, and fortunately it does triumph in this book: the wealth of material

garnered, with all its inherent complexities and inevitable contradictions, not

only speaks more eloquently than any theory ever could, but also tells us that

perhaps in the end no two cultures can ever be “impossibly distant”. This

humanistic vision is for me a special strength of this book.

The paradoxes of the

encounter are chalked by the author in his first chapter, ‘Literary Contacts

through the Ages’, and these have been picked up by Dr Martin Kämpchen who has

written a Foreword. I was a little puzzled when I read the opening words in the

Foreword: “Bengal and Hungary – what

could possibly be the connection between Bengal’s

culture and the culture of this small and seemingly insignificant European

country? Where is Hungary

anyway? Even if an educated Indian were asked these questions during a quiz,

many of them would probably produce a blank.” Martin – as he is a friend of both

Imre and myself, I hope I am allowed to call him by his first name too – then

goes on to make up a list of possible connections between the two regions that a

well-informed Indian intellectual might be aware of. Actually, I would have

thought the list was pretty good, indicating a high level of awareness! Two

other countries of the world, picked up at random, might not generate an equally

interesting list! I then found the origin of what Martin is saying in the

following words of Imre in his first chapter:

“Bengal

and Hungary

are two places between which until recently there has been virtually no direct

economic or political contact. Many people in one place do not even know where

the other is. Whenever I am in Calcutta

or elsewhere in Bengal people are keen on

asking me where I am from. The name of Hungary – besides being understood

as ‘hungry’ – does not ring a bell for most of those who question me. If it

does, then it is football .... In turn, for many Hungarians, the name of Bengal represents nothing more than the

Bengal

tiger.”

Well, another German

friend (a noted literary translator named Dr Joachim Utz) once told me that even

in his country, famous for its Oriental scholarship, to ordinary folk Bengal

meant, first and foremost, the Royal Bengal Tiger; so Hungarians needn’t blush

because of the lack of information in members of their ‘Lumpenproletariat’. I

once met a young Hungarian woman, roughly of Imre’s generation, who had never

heard of Mahatma Gandhi. For me that indicated a serious hiatus in her school

education and general knowledge. The young lady’s mother, who was of my

generation, was visibly embarrassed by her daughter’s ignorance and immediately

tried to tell her daughter in a hushed voice that Mahatma Gandhi was indeed an

important man of the twentieth century. I feel similarly embarrassed by those

Bengalis who have never heard of Hungary and

confuse the name with the word ‘hungry’! Since then I have had some e-mail

conversation with Imre about these points, which throws further light on the

complexities of human perception.

Could Hungary be

called a “small and seemingly insignificant European country?” In his first

chapter Imre calls it “a small country: its area ... more or less equivalent to

that of the state of West Bengal”.

So it is small in size compared to other sovereign nations in

Europe, but just as West Bengal is significant enough to some of us, so must Hungary be to

Hungarians. Looking at the map of Europe, we

find other countries which are smaller, such as Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, or

Slovenia,

each region significant to its inhabitants. Imre points out to me that I have

travelled and know a lot about the geography of Europe,

whereas in India

most of the educated people he meets do not seem to know much about Hungary and come

up with the joke about “hungry”; to them he is just “an angrez”. I feel even

more embarrassed when I learn this, because more than anything this suggests an

identification by skin-colour. Are all white people simply “angrez” to some

Indians? Shall I take some paltry, parochial consolation in the fact that those

who regard him as “an angrez” cannot be Bengali-speakers?

But it is not that I

know of Hungary

because I have travelled in Europe and thus

know about its geography! My truth (and pride!) is that I have been aware of

Hungary since my childhood in Bengal – first because I was born in the war years

and my mother used to explain that distant war to me with the help of a map of

Europe spread on the dining-table, on which I used to lean with great

wonderment, and secondly because geography was an important subject at my school

and was very well taught. Indeed, in my school years I had even heard of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire which had existed once but didn’t in my time. So perhaps

I just happened to have attended a school that was academically excellent? But I

also knew, since my childhood, of the half-Hungarian artist Amrita Sher-Gil and

the Hungarian woman named Eta Ghose who had married a Bengali, and these bits of

information were obtained not through school but through totally different

artistic and literary networks.

Above all, I was

aware of Hungary

because of the Tagore nexus. I had stared long enough at the hand-written

title-page of Lekhan, signed “Srirabindranaththakur/ Budapest/ 26 Kartik/ 1333”, and his prefatory

words to that collection, dated “Nov. 7. 1926/ Balatonfüred, Hungary”. Long

before I read Rani Mahalanobis’s account of her travels in Hungary with

Tagore, I was aware of Tagore having planted a tree there, by

Lake Balaton, and thus of the Hungarian connection as part of my

Tagorean heritage. The other point I have been aware of at least since my

twenties is that Hungarian names of persons and places were important in the

mental map of a major Bengali lexicographer working before the Second World War,

and I am delighted to find that Imre also refers to him in his first chapter:

none other than Jnanendramohan Das, whose dictionary is indispensable to those

of us who write in Bengali. As Imre correctly infers, the large number of

Hungarian names listed in Das’s Appendix of foreign names, with guidelines on

pronunciation, indicates the importance of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy in Europe before the First World War.

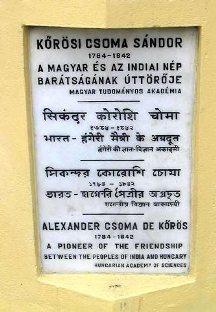

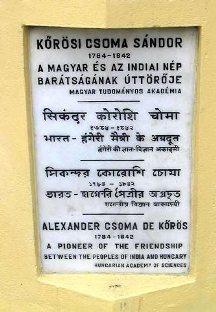

Alexander Csoma de Kőrös's tomb

and inscription on the tombstone

|

Since my student days

the other, more personal factors in my awareness of Hungary were first, my love

of gipsy music, of which I knew Hungary was one of the notable homes, and

secondly, my study of philology at college, through which I knew that Hungarian

was not a member of the Indo-European family of languages, but of the mysterious

Finno-Ugric family. Later, when doing my doctoral researches, I heard about that

intrepid Hungarian traveller and scholar, Alexander Csoma de Kőrös, who lies

buried in the outskirts of Darjeeling. Later still, when working on

Tagore and Victoria Ocampo, I found out about the Hungarian artists, mother and

daughter, Elizabeth Sass-Brunner and Elizabeth Brunner, who came to visit Tagore

in Santiniketan. And finally I take pride in being the first Bengali to read the

English translation of that Hungarian best-seller, Rózsa Hajnóczy’s The Fire

of Bengal, when it was still in typescript form! The Hungarians cited above

and many more colourful personalities enrich Imre’s survey of the

Hungarian-Bengali contacts in the past two centuries.

This question of how

much the general public of one country happens to know about another has set me

thinking deeply about this whole business of the acquisition of mutual

knowledge. Let me set some of these thoughts down here, as I think they are

quite contextual. So much depends, really, on the educational philosophies of

different countries. I consider myself lucky that my schooling happened in the

years immediately after India’s

independence, when, by way of a post-imperial legacy, an enormous emphasis was

put on ‘knowing the world’. The thinking went somewhat like this: every little

mole or vole knows his little hole, but as we are human, we have to know the

whole world, its far horizons and oceans, and the distant stars. In my school

the serious study of ‘the world’ began in high school geography. With an

exemplary dedication our Malayali Christian geography teacher started us off

with South America, the continent she imagined to be the

furthest from us physically and mentally. To her the goal of education was

precisely the mastery of terras incognitas. Exposure to such thinking in

one’s formative years shapes one for a lifetime. There was no way that I

could come away from Miss Varkey’s lessons not knowing where Hungary was!

Ever since those days I have known that the capital of Hungary is made

up of two cities, Buda and Pest, with the

mighty Danube flowing between them. Indeed, the

Danube became my favourite European river, and I used to love

tracing its magnificent curves in map-drawing classes. In the end, live

connections between different countries or cultures are made by a special set of

people, who can act as messengers, intermediaries or bridge-builders. Born in

Hungary

and writing his doctoral thesis in Hindi, Imre himself is clearly one such

person. Martin Kämpchen, the German scholar with a base in Santiniketan, is

another such person. Likewise, though I have never actually set my foot on

Hungarian soil, I love Hungarian music, Hungarian goulash with lots of paprika,

and the poetry of Miklós Radnóty when I can get hold of it in translation. So

perhaps I am also one of those people specially interested in making and

understanding human connections, which is why Hungry Tiger is just the

kind of book which speaks to me and delights me.

I therefore agree

with Imre when he says: “Many theoreticians interpret the exploration of the

world in its diversity as a struggle for power. For me it was enough to see my

nine-month old son’s delight in exploring every nook of any room or kitchen to

be reminded how limited this approach was.” Wisely, he tries to avoid seeing

literary productions and receptions in terms of just power-struggles. Not that

he is unaware of the fact that the material he has assembled can indeed be read

“in the light of the post-colonial theories”, yet he reminds us that Hungary was not

one of the colonizing, maritime powers of Europe.

“On the contrary, in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries it almost

functioned as a Hapsburg colony.” Hungarian readers would therefore often feel

greater sympathy for the Indian struggle for freedom from colonial rule than

with the colonial rulers. The search for Hungarian roots in the East lent extra

strength to that sympathy. It was only about 1100 years ago that the Magyar

people settled in the territory that has become known as Hungary. They

did integrate into Christian Europe, but nevertheless “they have always been

conscious of their eastern roots”.

There are indeed some

interesting parallels between the Bengalis and the Hungarians in the way their

histories have unfolded, and Imre himself as well as Martin in his Foreword

foreground them. Both the linguistic-literary traditions are about a thousand

years old. I confess that I was puzzled when I read the following sentence in

the Foreword: “Their respective literatures share a thousand-year-old history

with their origins in classical languages: Sanskrit and Pali with respect to Bengal, Latin with respect to Hungary.” This seemed to contradict

the origin of Hungarian in the Finno-Ugric family. But I realize what has

happened. Martin is referring to a sentence of Imre’s in the first chapter:

“Both Bengali and Hungarian languages look back to a history of about a thousand

years, at the beginning of which classical languages were literary languages:

Sanskrit, Pali etc. for the Hindu and Buddhist Bengalis and Latin for the

Christian Hungarians.” It is not that the Hungarian language originates in

Latin, but that when Hungarians began to develop literature in their mother

tongue, Latin was the literary language of Christian Europe, including the

Hungarians. The shorthand style of reference in the Foreword has resulted in a

sentence that might be misinterpreted, and this perhaps needs to be rectified in

the second edition of the book. Imre has explained to me by e-mail that the

relationship of Hungarian to Latin is rather like that of Telugu and Sanskrit. A

vernacular can absorb learning from a cosmopolitan language of a different

family and in the process absorb some of its essential vocabulary.

Perhaps another

shorthand reference has occurred in the Foreword in the following sentence: “...

both peoples were under foreign rule and broke lo[o]se only in the twentieth

century.” I presume the reference is to Hungary’s relationship with Austria, but I

feel that the question of ‘foreign’ rule is a matter of definition. The Magyars

themselves arrived ‘from outside’. Some Bengalis might feel that Delhi rule,

whether Mughal, British, or modern-Indian, is foreign rule, just as some

Scottish people feel that ‘London rule is foreign rule’, or just as the British

resent EEC diktats issuing from Brussels. Being under any kind of imperial rule

or within some sort of federal consortium the centre of which is a few hundred

miles away can be felt as constricting ‘foreign rule’, which is why

post-imperial states so often explode into fragments. I have discussed this

point with Imre and he agrees with me, saying that the distinction between

‘foreign’ and ‘national’ is usually the creation of modern nationalism, and

pointing out how Bangladeshis would now consider

Delhi

to be a ‘foreign’ ruler. Those of us who were children in the forties and had

grown up playing with children of diverse communities received, in 1947, the

perplexing message that Hindu and Muslim Bengalis could no longer live together

in friendship within one nation. I haven’t forgotten the jolt – how

incomprehensible the message seemed to me at that time.

East Pakistan

regarded West Pakistan first as a co-sharer

within one new nation and then as an oppressive ‘foreign ruler’. All cosy

feelings of compact, tribal nationhood as well as disturbing perceptions of the

‘foreignness’ of ‘others’ are in the end constructs.

Imre explains in his

book that from the end of the seventeenth century Hungary was part of the Hapsburg

Empire in a subordinate position. In the mid-nineteenth century there was an

unsuccessful war of independence, followed by years of “passive resistance”,

when the Hungarians drew inspiration from the Indian Mutiny. In 1867 Hungary reached

the same status as Austria

within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After the First World War, Hungary became a

sovereign state, but only at the expense of a partition that caused it to lose

more than two-thirds of its historic territory to its old and new neighbouring

states. The partition, and the consequent creation of two streams of literary

writings (in this case within Hungary and outside Hungary) are

indeed striking parallels between the fates of Hungarians and Bengalis. Another

parallel between West Bengal and Hungary is the

experience of communist rule, albeit within different frameworks. And communism

has played a most interesting role in Hungary’s perception of Tagore, with

his reputation rising and falling in accordance with shifts in political

thinking.

In his wide-ranging

assemblage of material Imre demonstrates that “it is sometimes interest in the

different and sometimes interest in the similar” that motivated

the Hungarian-Bengali interactions. This history is often one of

misunderstandings, yet it helps us to understand the other side as well as our

own.

It was Rabindranath

Tagore – who else? – who was the first person to write in Bengali about

Hungarian literature. I still remember the excitement with which Imre told me

that I simply had to read Tagore’s 1894 article ‘Sahityer Gaurab’, published in

the magazine Sadhana. The article had been included in the first edition

of the book Sahitya, but I could not locate it in my

Rabindra-rachanabali edition. It wasn’t there; it had been dropped. Never

mind, Imre sent me the necessary pages, photocopied. In this article, touching

the popular Hungarian novelist Mór Jókai, two of whose novels Tagore had read in

English translation, we can see that Tagore’s “interest was attracted by

Hungarian nationalism in its full bloom”. He admired the way nationalist

sentiments had helped to consolidate Hungarian literature, and regretted the

lack of that consolidation in his own territory. In view of his rejection of the

competitive and politically aggressive nationalisms of an Europe of a later

date, this early admiration of Hungarian national feeling leading to a

celebration of literature is indeed striking, showing how his thinking has never

been static, but has continuously evolved under the pressure of diverse

experiences. Hungary was a

non-colonizing nation that had recently emerged from its subordinate status, so

in 1894 it was possible for Tagore to sympathize with its nationalist feelings,

which taught Hungarians to be proud of their writers, such as Mór Jókai. Tagore

wished that Bengalis could learn from the Hungarian example and be proud of a

writer like Bankimchandra.

Hungry Tiger

is a well constructed book, Imre’s own survey being laid out into six major

chapters, the title of each clearly indicating its scope. The first chapter, to

which I have already referred several times, is entitled ‘Literary Contacts

through the Ages’, and the remaining five are: ‘Hungarian Travellers in Bengal’,

‘Tagore’s Reception in Hungary’, ‘Tagore’s Poetry in Hungarian’, ‘The Visit of a

Poet-Prophet in Hungary’, and ‘Tagore’s memory in Balatonfüred’. The scholarship

throughout is detailed and impressive, and the style of presentation is

attractive, without the clutter of jargon, which makes reading the book a

pleasurable experience, drawing the reader right into the heart of the

narratives. Imre, I know, is continuing to gather more relevant material, which

will hopefully go into a second edition of the book one day.

I have particularly

enjoyed learning more about the Tibetologist Csoma de Kőrös, who has been one of

my heroes ever since I did my doctoral researches in the early seventies. Later

in the twentieth century efforts had apparently been made to see Csoma in a

negative Saidian framework, as someone whose scholarship was in the service of

British interests in Tibet.

I am delighted to see that Imre exonerates Csoma from that charge: “Csoma can be

considered as one of the most notable examples to contradict Saidian

essentialism.” True, without the British presence in India and some of their

intiatives, requests, and assistance, Csoma’s scholarship might not have borne

fruit, but Csoma, “who was a Székler from Transylvania, an ethnic group that in

his times claimed continuity with the Huns of the fifth century”, was fired

first and foremost by “a universal human curiosity in exploring the unknown” and

secondly by the patriotic idea of finding the roots of his own people in Asia,

which is “nationalism in its most positive sense”. He fulfilled his promise to

the British and found out all he could about Tibetan, writing the first grammar

of the Tibetan language in English, and compiling the first Tibetan-English

dictionary, works which are landmarks in nineteenth-century Oriental

scholarship, but when he found that Tibetan was not related to Hungarian, he

learnt Sanskrit and some Indian vernaculars including Bengali in the same

quest. When he didn’t find the necessary links there either, “he set off for Lhasa and Chinese Turkestan to investigate the

possibility of a Uigur-Hungarian relationship”. This restlessness shows a

lively, inquistive mind rather than any political motivation. Talking of

Uyghurs, once having heard Uyghur performers from Chinese Turkestan sing and

dance in Oxford,

I was so captivated, and so utterly intrigued by the resemblances between what I

heard and northern Indian music that I was driven to write a poem about that

experience! We know of Tagore’s poem ‘Sagarika’ and his thrill in discovering

the traces of ancient Indian influence in the cultures of

South-East Asia. So I sympathize, and agree entirely with Imre when

he movingly says: “He [Csoma] was not working to present the Oriental people as

the ‘others’, but was searching for relatives.” Searching for relatives –

that’s precisely, and paradoxially, what we are often trying to do when we are

ostensibly surveying ‘others’: we are not trying to distance ourselves from

those ‘others’, but actually trying to come closer to them! Csoma was indeed

searching for the ethnic origins of his people through a study of Oriental

languages, but a search for relatives can be metaphorical rather than

genealogical. We do search for people with whom we can be friends, with whom we

can sense some spiritual affinity, or to put it in a modern idiom, with whom we

are on the same wave-length. When Imre came to talk to me in the Rabindra Bhavan

in Santiniketan with a big beaming smile, expecting to be accepted instantly as

a friend, he was doing something similar. I am thrilled to know from this book

that Csoma continues to be held in high esteem by Bengali scholars, that

Hirendra Nath Mukherjee, while still a student at Presidency College, wrote a

short biography of Csoma which was published in the Presidency College

Magazine in 1926, which was later expanded into a full-length book, and that

another Bengali, Durga Charan Chatterji, composed a quatrain in Sanskrit in

praise of Csoma’s scholarship.

The coverage in this

book of the other Hungarians who visited Bengal, including Ervin Baktay (the

maternal uncle of Amrita Sher-Gil), Julius Germanus, the Professor of Islamic

Studies at Visva-Bharati, Germanus’s wife Rózsa Hajnóczy who supposedly authored

The Fire of Bengal, perhaps with some help from her husband, the two

artistic Brunners (mother and daughter), and Eta Ghose who was married to the

poet Kanti Ghose, should be of interest to Bengalis. The stories are told with

all their complexities and ambivalences. For instance, in 1929 Baktay felt the

Santiniketan campus to be “alien and artificial”, and found a disappointing

discrepancy between the experience of reading Tagore’s literary works and his

manner of holding himself aloof in real life: he “seemed to be posing coldly in

direct personal communication as if he was always aware of his every gesture,

every word. I have felt the poet, in whose works I have found so much beauty and

value, to be alien.” One sees here some of the inherent pitfalls of

cross-cultural transactions, especially if one of the parties has become a

celebrity. The celebrity is afraid of being ridiculed or misunderstood or

imposed upon, so is afraid of opening up, and becomes defensive. This is then

interpreted as ‘posing’.

Germanus’s responses

were extremely complicated. He was disappointed with Santiniketan and in some

ways Santiniketan was not very satisfied with him either. In later years, he

developed an idealized and nostalgic view of the place, which was probably

motivated by Hungary’s

changing politics. As Imre explains: “...in the early fifties – the years of

Hungarian Stalinism – Tagore was discarded as an idealist whose world-view did

not help to strengthen the official ideology of materialism. From 1956 on,

however, he was considered to be a representative of the writers of the

colonised Third World who fought against

imperialism. In consequence he had to be praised.” As for Mrs Germanus’s The

Fire of Bengal, based to a large extent on the couple’s life in Santiniketan

and travels in India, with some fictional elements, I did give Imre quite a bit

of feedback when he was writing this book, and I agree with his overall

assessment that genre-wise it can be compared to the Romanian Mircea Eliade’s

Maitreyi, which will no doubt be familiar to some who are reading this

review. It should be pointed out that both Germanus and his wife display quite a

bit of Europocentric arrogance even though Hungary was not a colonizing power.

I hope what I have

said so far will whet the appetite of readers for the chapters that relate very

directly to Tagore. These are exemplary in their overview of material available

in a plurality of languages and in the mastery of detail. The account of

Tagore’s 1926 visit to

Hungary, moving effortlessly between Hungarian

and Bengali sources, is quite a tour de force in its sweep and colourful

qualities, and in its warmth, human understanding, and compassion. Imre

emphasizes that Tagore and his travelling companion Mrs Mahalanobis felt very

much at home in Hungary, more there than almost

anywhere else in Europe. I shall just refer to

two points that struck me in this Tagore-related section. The first is from the

chapter ‘Tagore’s Reception in

Hungary’ and gives us an insight into the

necessary psychological complexity of responses to ‘foreign’ artists:

“In the 1920s,

Tagore’s ideas received responses from authors who were born or lived in regions

lost after the World War. The reason for this is not simply that apart from

Budapest

the centres of Hungarian literary life fell outside the new boundaries. Even

from among the Budapest-based writers it was the ones whose hometown[s] had been

‘lost’ that[who?] wrote about Tagore. They had an additional motivation to

perceive the irrationality of western thought that led to a war and then to a

peace that they considered unjust. Their disillusionment urged them to examine

whether Rabindranath would offer an alternative to western thinking.”

I believe this kind

of reaction may have parallels elsewhere – in Slovenia perhaps?

The other point is

from the chapter ‘The Visit of a Poet-Prophet in Hungary’. The two essential aspects

of this encounter have been rightly highlighted. One is Tagore’s own “deep

desire to experience expressions of humanity in different people all around the

world”. Yes, Tagore too believed in ‘knowing the world’; he was, as we know,

thirsty for the far horizon. The other aspect is the way the Hungarians

reciprocated, how they in their turn tried to reach out to him in a very human

way:

“Among the

inconveniences of celebrity and the innumerable cases of misunderstanding there

were also some spontaneous moving events during the journey. It is enough to

remember the children of Professor Korányi or the villagers singing at the

window of the poet. In many instances meeting Tagore brought out the best in

those who saw him and the dividing line between East and West was dissolved on

the ground of common humanity as in the case of the Gipsy group leader Béla

Radics’s [gipsy violinist] visit to the sick poet ...”

This analysis has a

strong resonance for me, reminding me of the many similar moments of

cross-cultural human sympathy I found recorded in the journals and memoirs of

the British in India

in the 90-year period before the Mutiny, which was the area of my own doctoral

researches. And there are of course many such moments in Tagore’s own memories

of his international travels, from his very first visit to England in 1878

to his visit to Persia

in 1932. There are clear parallels with Tagore’s experiences in Argentina only

two years prior to his Hungarian sojourn. There too, as in Hungary, he was

ill, but he still wanted to meet people and talk to them. The Hungarian gipsy

violinist Béla Radics standing by Tagore’s bedroom door and playing to soothe

and heal him, but not entering the room, as described by Rani Mahalanobis,

reminds me of the Castro quartet that played Debussy, Ravel and Borodin for

Tagore in Miralrío: the musicians were in the hall on the ground floor, while

the poet, not feeling well, remained in his bedroom at the top of the stairs,

with the door ajar. And that cannot but remind us of that misadventure in England

recalled in Jibansmriti, hilarious and lugubrious at the same time, when

the teenaged Tagore, after an evening of travail, had the very next morning to

sing a lamentation in the raga Behag, penned in English by an Indian, in

front of the closed door of a sick lady.

The six chapters

written by Imre himself are followed by some Appendices. Appendix A presents

carefully chosen and suitably introduced documentary material that greatly

enhances the value of the coverage in the main survey, while Appendix B provides

a list of newspaper articles relating to Tagore in the Hungarian Press. Appendix

A, ranging from Tagore’s 1894 article on Hungarian literature, so generous in

spirit, to Georg Lukács’s notorious 1922 review of Ghare-Baire, in which

he foolishly dismissed the novel as “a petty bourgeois yarn of the shoddiest

kind”, is a real winner. Anybody who wishes to gain an insight into how ideology

can enslave the intellect should read the Lukács piece. My own favourites in

this section are the short story ‘The Tree that Set Forth’, the poem ‘Towards

the Eastern Sunrise’, and the engrossing extracts from Elizabeth Brunner’s

unpublished autobiogaphy. I was also moved to read, in Baktay’s account of his

visit to Tagore, of Tagore’s tree-house “on the edge of the Surul campus”,

accessible only with the help of a ladder and complete with a tiny bathroom.

That is where Tagore used to retire when he wanted real solitude. Seeing it,

Baktay was suddenly “overcome by deep compassion for the Poet”. Tagore had

created “a small new world around him”, but sometimes that creation of his

became a burden to him, and he had to escape from it. There are some very

genuine insights, too, in the article on Tagore by István Sőtér.

In conclusion, I

would recommend this book to all who wish to understand the delights as well as

hazards of cross-cultural meetings.

Reading

Hungry Tiger and remembering other narratives of such meetings have made

me think a lot about these issues, so let me indicate in brief where those

thoughts have led me.

First, the purely

literary aspect of such a meeting depends, of course, very much on whether the

two sides can read each other’s texts, and failing direct access, on the

availability of reliable translations, but it also depends on the cultural mood

of those receiving the new input. If the latter think that they are going to

receive something that will expand their intellectual and artistic horizons

while enriching and nourishing their own identities at the same time,

they will sometimes go out of their way to dig for the new riches and discover

meaning in them. Even re-translations will be meaningful for them then. It was

along such a route that the publications of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, the

Asiatick Researches, took Europe by

storm at the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth,

expanding the horizons of European scholars, making them re-think their notions

of the Orient, and modernizing their outlook. A similar process took place in

the explosion we call the Bengal Renaissance. Sometimes a search for roots,

sometimes a sense of loss or of impoverishment, or a gnawing dissatisfaction

with ways of thinking that are felt to be outmoded will trigger a quest and

sharpen receptivity. But if the literati of a country have an entrenched

superiority complex which convinces them that they have nothing to learn from

others, even high-quality material that is available will not persuade them to

cast a serious glance at it.

Secondly, besides the

interactions of elites, there are also important moments when the ordinary

people of a country are touched and moved by a foreign phenomenon, and the value

of such connective moments for human societies should not be underestimated

either, because they emphasize our common humanity and bring people of different

countries together. The same triggers as enumerated above can activate a

spiritual thirst amongst ordinary men and women, and cause them to seek

comforting and uplifting messages from a teacher from abroad, as happened in

post-war Germany

and Hungary.

Any such quest that increases the bonds of friendship between different peoples

needs to be cherished rather than diminished in our problem-ridden world. The

West has a double game that it loves to play, first seeking ‘gurus’ from the

East, then running them down for preaching to the rest of the world. Tagore has

often been a victim of this double game.

Thirdly, the media

play a shady role in this double game, first helping to make someone an

international celebrity, and then mocking him and pulling him apart..

Fourthly, though some

Orient-related scholarship of Western scholars may have been co-opted into

‘colonial’ or ‘imperial’ projects, not all can be described in such clear-cut

terms. Some scholars throughout the ages have been disinterested seekers of

knowledge. In other cases, terms such as ‘colonial’ or ‘imperial’ have to be

expanded or re-defined for the Saidian paradigm to deliver any meaning. The

arrogance of a Germanus was very Europocentric, but not in the service of any

empire. With or without empires, there can be a superiority complex that is

based on a group’s sense of achievement, material, intellectual, or spiritual.

Religious establishments and aspiring political ideologies can ooze as much

arrogance as actual empires. Lukács’s dreadful misunderstanding of Tagore was in

the service of communist ideology: perhaps we could say that it was in the

service of a communist imperial project, but Lukács himself would not have

viewed it as such. There can even be consolidations of power within the learned

communities which are hegemonic in nature: many a time have I marvelled at the

hegemonic attitudes of the so-called ‘post-colonial’ critics right across the

world, who by a term such as ‘Indian (or South Asian) literature’ understand

only what is written in English, devoting much energy and finances in elevating,

magnifying, disseminating authors in that category, while completely bypassing

those who write in the native languages of the region, rendering them – to

borrow a term from the Argentina of the days of military dictatorship –

desaparecidos, or ‘disappeared ones’. They seem to have a project of their

own too: is this also not a form of realpolitik, and are we allowed to call it a

‘neo-colonial’ academic enterprise?

I hope that the task

of translating Tagore into Hungarian directly from the Bengali will begin in the

not too distant future. Imre will surely agree with Martin’s point in the

Foreword that only after sufficient numbers of direct translations have come out

can there be a true re-evaluation of Tagore’s works in

Europe. Imre has himself translated a few poems of Tagore into

Hungarian, and I am sure could translate some more, perhaps in collaboration

with a Hungarian poet to advise on the final form and another Bengali who is not

just a ‘native speaker’ but understands the language of poetry. As the person

who knows both the languages in question, he would be the linchpin of such a

team. After attending an international poetry translation workshop in Slovenia in 2007, I am convinced

that intelligently and sensitively used, such a strategy can work. Using similar

methods, reasonable translations of Tagore’s prose could be undertaken too. And

I don’t mean that only Tagore needs to be translated; there is a plethora of

good writers out there, waiting to be translated. And it goes without saying

that Bengalis should translate from the Hungarian too. A few poems and short

stories have indeed been done, as Imre informs us in his first chapter, using

one or more intermediate languages. I recollect translating one poem of Mihály

Babits in collaboration with Imre. At the end of the day we have to face the

fact that unless there is some collaborative effort, the literatures of most

languages will remain untranslated. And unless there are reliable translations,

there will be no end of misunderstandings.

I only wish Sahitya

Akademi had taken a little more loving care of such a scholarly piece of work.

In spite of the book spending a long time at the printer’s, a few misprints

remain: not many, just a few, but enough to be disconcerting in a learned book.

The book could have also done with some copy-editing to regularize punctuation

and eliminate the occasional slips or infelicities of the kind that a polyglot

scholar is apt to make when writing in his second or third language. It is 99%

there, and publishers in

India, where everybody is now so proud of the

standards and achievements of ‘Indian English’, owe it to such scholars who have

made India their field, to assist them

with the remaining 1%. What good is the prestige of English in India if those

who handle it so confidently cannot offer a modicum of editorial assistance to a

scholar who has made it his business to study Indian languages and is at the

same time capable of delivering a book in English for the international

community, which is 99% there? Is this also a double game being played by the

Indian learned classes? Many who write in English in India cannot write in any other

language but that; here is a ‘foreign’ scholar who can write about India in three

languages. Surely he deserves some assistance from those who are English-savvy.

Let me give here one

instance of the kind of slip that can arise directly from a constant attention

to a plurality of languages. On p. 234 I read, about a book, that “it was

revised in several periodicals in October and November 1926”, where the author

clearly means reviewed, not revised. The root-meaning of both

words is roughly the same, referring to seeing or looking at something again,

but the active meanings have diverged. When speaking to me in Bengali, Imre

sometimes does something analogous: he uses a word in its Hindi sense, that is

to say, the word is common to both Hindi and Bengali, but the meanings have

slightly diverged, and Imre uses it in its Hindi nuance, because he is immersed

in teaching and studying that language. This is indeed a small matter, but I

feel that as Sahitya Akademi is a major academic publisher in India, a little

intelligent copy-editing to support the work of foreign scholars for whom

English is not a natural mother tongue and who are engaged in putting Indian

languages and literatures on the map of the world would be entirely appropriate.

By the way, “Prof.

Shibaji Bhattacharja at Jadavpur

University” who is thanked

in the Acknowledgements is surely the well-known academic Prof. Shibaji

Bandyopadhyay, and I hope he is not feeling too much abhimaan at this

metamorphosis of his surname. If a joke about caste is permitted, I would like

to point out that even in this slip his caste status has been respected! Again,

this is just the kind of slip someone at the publisher’s end could have picked

up and weeded out.

But my principal

regret is that Sahitya Akademi has not included a single photograph! In his

Acknowledgements, the author thanks “the Rabindra Bhavan in Santiniketan for the

copyright of several photographs”, but where are the photographs? This

book, which is so richly documented in the textual sense, is crying out for some

visual material, which would have made it a little more reader-friendly. Books

like this are always enhanced by a few photographs. Readers remember the

visual images and connect them with the text, with the story being told.

Printing a few photographs is surely no big deal in this day and age. Technology

has made such advances, and India is

supposed to be teeming with competent, advanced printers. If it is a question of

money, I am sure potential customers of this book would happily pay a few more

rupees to have a book which was a little more visually eloquent. Indeed, putting

in a few photographs is a good investment for a publisher, as it widens a book’s

market. I sincerely hope that this book will soon be given a second printing,

with the minor errors corrected, the title identical on the cover, the

title-page, and the ISBN page, and all the photographs restored.

As I finish this

review, I am happy to say that Imre has developed one of his chapters, with some

additional material, into an article for Parabaas, and has also provided

some photographs to accompany the feature.

©Ketaki Kushari Dyson

Photographs taken with permission from Shambhala files

Published in Parabaas September, 2008.

Send us your feedback

©2008 Parabaas

|

Hungry Tiger/ Encounter between India and Central Europe: The Case of Hungarian and Bengali Literary Cultures

by Imre Bangha. Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, pp. 344. ISBN: 81-260-2583-2

Hungry Tiger/ Encounter between India and Central Europe: The Case of Hungarian and Bengali Literary Cultures

by Imre Bangha. Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, pp. 344. ISBN: 81-260-2583-2