A brief note on three Portuguese translations of Tagore’s poem

"Where the mind is without fear"

From the first issue of India Nova

(May 7, 1924)

The First

World War had just been over.

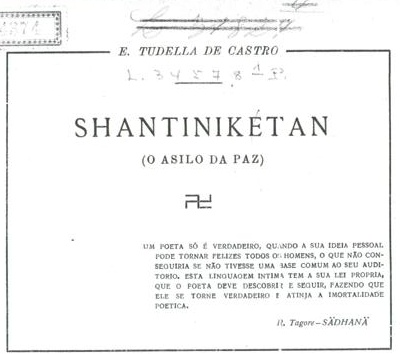

Lecture on Shantiniketan

Tudela de Castro, a Portuguese

scholar, delivered

on 11 May, 1923 a lecture at the Theosophical Society of Portugal on

Shantineketan, that is, Tagore’s university which is an expression of the ideas

of self-reliance that he strongly advocated for his countrymen under the

foreign rule. In his lecture, he read this translation of the poem “Where the

mind is without fear...”

Lá,

onde o espiritu está sem receio e a fronte erguida;

Lá,

onde o conhecimento é livre;

Lá,

onde o mundo não foi dividido por estritas paredes;

Lá,

onde as palavras dimanam das profundezas da sinceridade;

Lá,

o esforço infatigável estende os braços para perfeição;

Lá,

onde a razão clara não se afastou mortalmente para o arido e triste

deserto da convenção;

Lá,

onde o espirito por ti guiado se alarga

na expansão continua do pensamento e da ação;---

N’ste

paraizo de liberdade, meu Pae,(1) permite que a minha patria acorde.

(1) Referencia a Deus

Article with translation in India Nova

(Click to read in full)

We come across another translation of the poem in the first

issue of India Nova, the journal of

the Instituto Indiano founded at the

famous

Lá onde a

fronte se ergue aliva e

O espiritu

vive tranquilo;

La’ onde o

conhecimento é livre;

Lá onde o

mundo se não fragmentou ainda entre estrietas e acanhadas muralhas;

Lá onde as

palavras se brotam das profundas da sinceridade;

Lá onde o

esforços incansável estende os braços para a perfeição;

Lá onde a

corrente limpida da Razão não sofreu ainda um letal desvio

Para o

arido e sobrio deserto do costume;

Lá onde

espirito guiado, por Ti,

Avança

para o largamento

Continuo

do pensamento e da acção;

Nesse

paraiso de liberdade, meu

Pai,

permite que a minha

Pátria desperte

!

In 1969, a translation

of Gitanjali was published from Brasília. The translator is

Gasparino Damata. In fact, I was, for certain reasons, extra curious about the

translator, as there was, in the contemporary Brazilian literary arena, a

little known social activist-writer with the same name. Anyway Gasparino realised

the timelessness of Tagore’s work, though initially he argued with himself why

the youth of his time who adore liberty in every aspect of life and are steeped

in the pleasure of carnal love would read Gitanjali He

dedicated the translation for the ‘Year 2021’!

In 1969, a translation

of Gitanjali was published from Brasília. The translator is

Gasparino Damata. In fact, I was, for certain reasons, extra curious about the

translator, as there was, in the contemporary Brazilian literary arena, a

little known social activist-writer with the same name. Anyway Gasparino realised

the timelessness of Tagore’s work, though initially he argued with himself why

the youth of his time who adore liberty in every aspect of life and are steeped

in the pleasure of carnal love would read Gitanjali He

dedicated the translation for the ‘Year 2021’!

Onde o espírito vive sem

mêdo e a fronte se mantém erguida;

Onde o

saber é livre;

Onde o mundo não foi

dividido em pedaços por estreitas paredes domésticas;

Onde as palavras brotam do

fundo da verdade;

Onde o esfôrço incansável

estende os braços para a perfeição;

Onde a fonte clara da razão

não perdeu o veio no triste deserto de areia do hábito rotineiro;

Onde o espírito é levado a

tua presença em pensamento e acção sempre cresentes;

Dentro dêsse céu de

liberdade, ó meu Pai, deixa que se erga a minha pátria.

Besides these three translations of “Where the

mind is without fear...”, from time to time, its

Portuguese rendering was done by the readers who felt a sort of inner urge to spread its

message or simply to share it with others. Thus several translations appeared in different literary magazines and

newspapers in

Published in Parabaas May 7, 2010.

©2010 Parabaas