|

Translated from Bengali by Prasenjit Gupta

The story of humankind forms the conclusion to the many chapters that tell the history

of the earthís many creatures--this we have heard. In any human society we sometimes encounter the various animals that

live hidden within us--this we know. In reality we call that human which has

blended all the animals within ourselves, combined them into one: penned our

tigers and cows into one enclosure, trapped our snakes and mongooses in the same cage.

In the same way we give the name raag to that which combines all the sa-re-ga-mas

within itself and creates music--after which the notes can no longer make trouble--but still,

even within the music an individual note may stand out from the others: in one raag the ma,

in another the ga, in yet another the flat dha.

My nephew Bolai, my brotherís son: in his nature, somehow, the fundamental notes of plants and trees sounded the loudest. Right from childhood he had the habit of standing and staring silently, not exploring places like other boys. When dark clouds massed themselves in layers in the eastern sky, it was as if his soul became dense with the moist fragrance of the forest in July; when the rain came thrumming down, his whole body would listen to what it said. When the sunshine lay on the roof in the afternoon, he walked about bare-chested, as if gathering something into himself from all the sky. When the mango trees bloomed in the month of Magh, a deep happiness would enter his blood, in memory of something inexpressible; his inner nature would spread itself in all directions, like a grove of sal trees flowering in Phalgun, would become suffused, become deeply colored. At these times he liked to sit alone and talk to himself, patching together whatever fairy-tales he had heard, the tales of the pair of aged tattlers that had built their nest in a crevice of the ancient banyan tree. This wide-eyed-always-staring boy didnít talk very much; he would stay quiet, thinking things over in his head. Once I took him into the mountains. When he saw the green grass that covered the slope all the way down to our house, he was delighted. He didnít think the coverlet of grass was any fixed thing; he felt it was a playful, rolling mass, always rolling down. Often he would climb up the slope and roll down himself--his entire

body itself become grass--and as he rolled, the blades of grass would tickle the back of his neck, and he would laugh out loud.

After the nightís rains, the early-morning sun would peer over the mountain tops, and

its pale golden rays fell on the deodar forest; and without telling anyone heíd go

quietly and stand awestruck in the motionless shadows of the deodars, his body

thrilling all over, as if he could see the people within these gigantic

trees--they wouldnít speak, but they seemed to know everything, these grandfathers

from long ago, from the days of "Once-upon-a-time-there-lived-a-king."

His eyes, deep in thought, werenít turned only upwards: I often saw him walking in my

garden with his head bowed, searching for something. He was impatient to watch the

new seedlings lift their curly heads towards the light. Every day he would bend low to

them, as if asking: "And now what? And now what? And now what?"

They were stories always unfinished--tender young leaves, just arisen; he felt a

companionship towards them that he didnít know how to express. They too, seemed to

fidget in their eagerness to ask him something. Maybe they said,

"Whatís your name," maybe "Where did your mother go?" Maybe Bolai replied, in his head,

"But I donít have a mother."

It hurt him whenever someone plucked a flower from a plant. But he realized his

concern meant nothing to anyone else. So he tried to hide his pain. Boys his

age would throw stones to knock amlokis off the tree; he couldnít speak, he

turned his face and walked away. To tease him, his companions would stride down

the garden, slashing with a cane at the rows of shrubs on either side, in an

instant would break a branch off the bokul tree; he was too ashamed to cry, lest

someone think it madness. His most troubling time was when the grass-cutter came.

Every day he had walked among the grass, peering closely at it: here a green tendril,

there an unknown purple-and-yellow flower, so tiny; the occasional nightshade and its

blue flowers, in their hearts a speck of gold; along the boundary wall, a kalmegh vine; elsewhere an onontomul;

the small shoots just emerged from neem seeds pecked off the tree by birds,

how pretty their leaves--and all these would be weeded by the ruthless weeder.

These werenít the fancied plants of the garden, and there was no one to listen

to their complaints.

Sometimes he would come and sit on his auntís, his Kakiís, lap, and wrap his arms around her neck.

"Tell this grass-cutter, wonít you, not to cut down my plants."

Kaki would say, "Bolai, sometimes you talk like a madman. All this is becoming a

jungle, how can we not clear it away."

Bolai had learnt a while ago that there were some griefs that were his alone;

they sounded no chord in anyone else.

This boyís real age was the age, those millions of years ago, when,

from the womb of the ocean and the newborn layers of mud, the earthís would-be

forests rose and first cried out; that day there were no animals, no birds, no babble of

life;--on all four sides only rock and silt and water. The trees, leading

all other creatures on the path of time, raised their hands to the sun and said,

"I shall stay, I shall survive, I am the eternal pathfinder; after death and amidst

death, endlessly, I continue my pilgrimage of growth, my journey in sun and cloud,

through night and day." Even today that murmur of the trees rises in every forest,

on every hill and grassland; and from their branches and leaves, the life-breath of

the earth speaks out, again and again: "I will stay, I will stay."

These trees, the mute foster-mothers of earthís life, have through endless eons milked

the heavens to gather into the earthís nectar-cups the radiance, the essence,

the grace and power of life itself; and endlessly they raise their eager heads high:

"I will stay." And in some way Bolai had heard that call of the earth-being,

heard it in his blood. Weíd laughed about it no end.

One morning I was pondering the newspaper when Bolai ran up and hurried me into

the garden. He showed me a seedling and asked, "Kaka, what plant is that?"

I saw that it was a tiny silk-cotton plant that had taken root in the middle of the gravel path.

Bolai had made a mistake in showing it to me. Heíd noticed it when only a small shoot

had come up, like an infantís first incoherent word. After that he watered it

every day, checked it anxiously morning and evening to see how much it had grown.

The silk-cotton grows rapidly, but it couldnít keep up with Bolaiís eagerness.

When it had risen a handís breadth or two, he saw its rich leafage and thought

it was a prodigious tree, the way a mother sees the first hint of an infantís

intelligence and thinks, a prodigious child. Bolai thought it would astonish me.

I said, "I must tell the gardener, heíll uproot it."

Bolai started. What a terrible thing. He said, "No, Kaka, please donít, I beg you,

donít have it uprooted."

I said, "I donít know what gets into your head. Itís right in the

middle of the path. When it gets bigger itíll spread its cotton all

around and drive us crazy."

Unable to prevail over me, this motherless child went to his Kaki.

He sat down in her lap and hugged her. Whimpering and sobbing, he said,

"Kaki, you tell Kaka not to, not to have the plant cut."

Heíd found the right approach. His Kaki called me and said,

"Oh, listen! Do leave his plant alone."

I left his plant alone. If Bolai had not pointed it out in the beginning

I might not have noticed it at all. But now it leapt to my eye every time.

Within a short year it grew shamelessly large. And Bolai lavished all his affection upon it.

The plant began to look more and more loutish to me. Standing there, in the wrong place,

without a by-your-leave, just growing taller and taller by the hour.

Whoever saw it wondered what it was doing there. Twice or thrice I proposed the

death penalty for it. I offered Bolai the enticement of replacing it with several

rose bushes of high quality.

Then I said, "If you must have a silk-cotton plant, Iíll have another seedling put

in near the boundary wall. Itíll look very pretty there."

But whenever I mentioned cutting it he would flinch, and his Kaki would say,

"Oh, it doesnít look all that bad."

Bolai, crying, left his Kaki and went; our house was empty.

Two more years passed. Meanwhile, Bolaiís Kaki wiped her eyes in secret, and went

into Bolaiís empty bedroom to arrange and rearrange his torn pair of shoes,

his cracked rubber ball, his picture book of animals. Bolai has left all these

relics behind and grown much older, she sat and thought to herself.

One day I saw that the wretched silk-cotton tree had grown beyond all reason;

it was so overbearing that it could not be indulged any longer. So I cut it down.

At this time Bolai wrote to his Kaki from Shimla: "Kaki, please send me a

photograph of my silk-cotton tree."

He was to have visited us before he left for England, but that didnít come about. So he had asked for a picture of his friend to take along.

His Kaki called me and said, "Listen, can you go bring a photograph-walla."

I asked why.

She gave me the letter, written in Bolaiís unformed hand.

I said, "But that treeís been cut down."

Bolaiís Kaki didnít eat for two days, and for many days after that she wouldnít say a word

to me. Bolaiís father had taken him from her lap, as if breaking off the umbilical cord;

and his Kaka had removed Bolaiís beloved tree for ever, and that too shook her world,

wounded her in the heart.

The tree had been her Bolaiís reflection, after all, his lifeís double.

Glossary

Dada, older brother

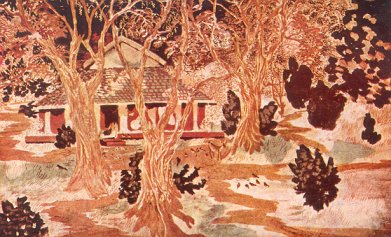

Translated by Prasenjit Gupta [Proshenjit Gupto ]. Prasenjit Gupta is a translator and writer living in Iowa City. (more) Illustration:

"Nichu Bangla, Santiniketan" by Nandalal Basu. Taken from Amader Santiniketan by Sudhiranjan Das (Visva-Bharati).

Click here to send your feedback

*

To learn more about the ITRANS script for Bengali,

click here

. |