For Books by Sirshendu Mukhopadhyay and others, visit

The Parabaas Bookstore

For Bengali movies (with English subtitles), visit

The Parabaas Moviestore

|

Translated from the original Bangla novel

My world went dark as the roof collapsed on

me. My limbs felt paralyzed. I wasn’t even breathing. Was I dead? Yes, most

certainly. I felt a twinge of sadness, but also a relief. This business of

death had been such a problem for me for so long. How would it be, painful or

not, any moaning and groaning, any embarrassing accidents? Would I be dressed

decently? Would my mouth be agape or in a smile? All these questions had

plagued me forever. Well, it’s over now. It happened quickly, and no, not with

too much pain or suffering either. With the problem of dying over with, I felt

rather lighthearted. Dying with such ease was definitely a sign of good karma. But

why did the roof collapse? Was there an earthquake? I didn’t feel any tremors.

I looked up. No, the ceiling looked quite intact. Not broken at all. But I

distinctly felt it collapse around me with a loud crash.

“Stroke patients sometimes feel like that.” I looked down and saw Ranajit on the sofa. He

had red socks on his right foot

and a faint smile.

“Stroke? No, no. I didn’t have stroke. It was the roof…”

“That is the stroke. When I had it, it felt like there was no ground

under my feet and I was falling down a deep abyss.”

“Are you dead too, Ranajit?”

“Why else would I wear red socks on right foot?” That’s true! This simple fact had escaped my

notice. Red socks on right foot meant death. I felt embarrassed at my own

stupidity. I

was only twenty-nine years old. Death came rather quickly for me. Still, what’s

the point in living eighty or ninety years when one has to die eventually. The

worry about death and fear of death would only increase as one grew old. That

is why we all try to hide our aging. Color our hair, exercise to defy

weaknesses. No, it is much better to be done with dying. Now I was free of all

those worries and fears. Granted, I did feel a bit of remorse, wondering what I

could have been or could have accomplished in the future, but at the same time

I didn’t have to sigh and moan anymore about what I could have or should have

done in the past.

Ranajit pulled up his socks, “OK, I’m off.”

“You’re leaving?” Where was he going? Was there some place to go

after death? For sure there weren’t any office, school, morning or evening

walks, movies, plays, meetings, shopping or visiting in-laws after death. So

where was Ranajit going? I

felt worried. Was there a place to go after death? Then there must be returning

too. Going where and returning from where?

The room around me looked partly familiar. There was an old, worn sofa,

a dusty centerpiece, a glass-fronted shelf, TV set. A naked yellowed bulb hung

from the ceiling emitting only a dull glow. There was no day or night here, the

light seemed to be glowing since the beginning of creation and would go on till

the end of time. Everything else in the room was dead, inert, and useless.

Then where did Ranajit go? Or was it because of me. Was I the one who

replaced him?

There definitely was no winter or summer here, no dawn or dusk. I felt a

bit alone, a bit afraid.

Suddenly that lethal sound started. Some cuckoo started pouring out its

mournful call filling all the space around me. I

covered my ears and shrieked, “Why? Why are you calling again? You killed me

once, long ago. Did I not die? Want to kill me again?” In

that far away early morning, in a foggy wintery garden, this cuckoo had slain

me with its calls. I had knelt on the dew-drenched grass, covering my ears, my eyes flooding with tears, and

realized the intense pain of my dying. After a long time when I left my corpse

and stood up, I was not Runu, I was a different boy. I was a different boy. I was not the same old myself. And nobody

knew that except me. No.

Correction. There was one other person who came to know it too. She was my

mother. That morning when I returned home, she stared at me for a long time,

and then pulled me close, bit lightly on my left little finger and caressed my

head. She knew that I was not the Runu who went to the garden that morning. I

was someone else. But she never told anyone about it.

Strange! Had that cuckoo come back to slay me once more? Could someone die

more than once? I

stared in daze. Who

had drawn this ghostly morning? Done in black and gray pencils, or ash colored.

Deep, somber. I was familiar with this morning. I had met it many times while

jogging in the college compound, in t-shirts, shorts and trainers. Someone

expertly drew this morning around me. Who was he? Nobody could draw like him. I

looked again with sleepy eyes. Was I born again? Surely I did die.

Thus I died and became reborn, again and again.

The Artist drawing the morning didn’t like his own drawing. So he put a

red gold sun in the middle of ash grey morning, then spread deep blue in the

sky and unending bright green all around. Crazy artist! I

sat up in that morgue of a room. I had to identify my own dead body, everyday.

This was I, Runu, Ranajit Bharadwaj. Hard to tell if he was alive or dead.

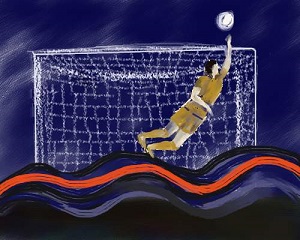

Perhaps a bit of both. It had rained last night and raining this evening too. Heavy rain obscuring the backdrop of the trees. I was

standing erect like a snake in the square of the goalpost and watching the rain

blur the colors of the jerseys of both the teams. It was hard to tell the teams

apart. Hard to judge who was running with the ball or who was passing to whom. A few players were needlessly running around with ball without knowing what to do with it. I

was momentarily lost in thought when suddenly the ball flew at me. I jumped but

could not grip it. The ball slipped my hand and rushed towards the goal.

Fortunately, a puddle near the post slowed it, so I dove again and managed to

catch it, thus saving our team three points. A few spectators were sitting

under the umbrellas. But no one clapped. I

was supposed to be sleeping in late today. But I felt a headache and couldn’t

open my eyes in the bright light.

“Hello there! You will really get into trouble one of these days. You

again forgot to close your door.”

Yogeshda had on t-shirt, shorts and sneakers and was carrying a ripe

‘bel’ (wood-apple) in one hand and a newspaper in the other. I

looked at the bel, “Where do you get ripe bel at this time?”

“Why? You want one?” “No,

just wondering. This is the end of monsoon, not yet the season.”

“This is Kolkata. If you have the money, you can get anything in all

seasons.”

“True, true. Man is not dependent on seasons anymore.” “

Did you overdo it last night?” Yogeshda asked sotto voce.

“Hard to keep track when it’s not my money.”

“But the body is yours.” I

wanted to lay down again, “What’s the time?”

“Eight o’clock. What was it? Scotch?”

“Many kinds. Scotch too. Can’t tell who fed me what.”

“That is the problem with you. You have to be faithful to one kind of

drink, like a good wife and stick to it.”

“What’s the difference?”

“Whether it is gin, vodka or scotch, if you stick to one kind you will

feel like a royalty, you will sprout Shakespeare, sing Rabindrasangeet or

classical. If you mix drinks, you will feel like strangling someone, starting a

fight, or punch the waiter or caress someone else’s wife.”

“Goodness! Hope I didn’t do anything like that last night.”

“How would I know! I didn’t see you last night. Now coming home from my

morning walk I see your door ajar. Just like last week. Now get up and check if

anything is missing. According to the latest police report, the thieves in Salt

Lake are as thick as the mosquitoes.”

“Did they actually count the mosquitoes?”

“No, nor the thieves. It’s all statistics, my friend. Even if it were

wrong, people would believe it. You should too. Now please lock your door in

future.”

Yogeshda in imported shirt and brand name sneakers was not a person to

be dismissed. Albeit short, balding and with a wide girth, he was very smart

and professional. He was now eyeing my weights hungrily. They were ten kilos

each, “Do you lift these everyday?” “Arms

are the assets of a goalkeeper.” I smiled shyly. “Well, Arms are assets for everyone.

Goalkeeper, typist, even beggars. I

was still staring at his bel.

Lamding used to have hundreds of bel trees, over and around the fields;

they were everywhere and bore tons of sweet bels. I was tempted but could never

climb trees. I had always been scared of heights.

Biju used to climb trees. Biju had a mysterious understanding with the

trees. He could climb even the slimmest branch which nobody would dare grab on.

From up there he would throw down the ripe fruits at us. Some we caught, some

hit the ground and burst. Then we would all sit around and feast on those bels.

What joy!

“What are you thinking?”

“Your bel. Remembering my old days.”

“You know how much it cost? Forty rupees! Inedible crap. Only useful for

moving bowels.” I

didn’t say anything. There was a time those bels tasted like nectars to us.

Yogeshda was still eyeing those weights, “Would lifting weights make me

trim?” he asked, “Doctors keep asking me to walk, but walking hasn’t reduced my

weight at all, I didn't even lose half a kilo. Just sweat and exhaustion.”

“Perhaps it will.”

“Can I try it?”

“Sure, go ahead.” He

put down the paper and the bel on my table and approached the weights like a

kid with a new toy. First he tenderly touched them.

“Think I can lift?”

“Sure. Just do it slowly. Don’t pull any muscles.” He

lifted them. His face got red. “Pretty heavy. Ten kg each. Not easy.”

“They feel heavy in the beginning, then you get used to it.”

“That’s why you have no fat!” “If

I did, I will be thrown out of the club.” He

lifted the weights a couple of times more and then carefully placed them back

on their cradles. Then he wiped his face in a Turkish towel taken out from his pocket and

smiled happily, “I exerted more by lifting these than by walking for forty

minutes. Perhaps I should buy myself a pair. What do you say?”

“Sure, buy a pair.” I

never thought lifting weights could make a grown man so happy. Perhaps his own

weight was bothering him. Could very well be. His wife Bandana was a very

smart, sharp looking woman. Rather snobbish, not a great beauty but had a strong personality, sharp eyes, low cut hair

and always tastefully clad in sarees. She was fairly tall, wore rimless glasses, definitely a couple

of inches over Yogeshda. Yogeshda was often heard to complain that he was fed up of her strict rules. It was natural for her to be displeased with his

corpulence. Perhaps she was the reason behind all this talk about exercises and

walks. I

often met Richa in the landing or in elevators. She was seven. She always said

‘Hi’ to me. In our first meeting she had said, very seriously, “Dad says you

are a gold keeper. What is a gold keeper?” I

said, equally seriously, “No Richa, not a ‘gold’ keeper, just a poor

‘goal’keeper.”

Richa, still worried, “And what does a goalkeeper do?”

Then with a lot of gestures and drawings I had explained how a

goalkeeper stood alone in front of a rectangular frame made with three pieces of wood stopping goals. “Is

Lionel Messi a goalkeeper?” “No

Richa he is not. He makes goals.”

“Did he make you any goal against you?”

“No, but others like him did.”

“But why?”

“That is the problem. They shouldn’t but they do. Some people score

goals and some block them.” Two

months ago I gave Richa a real football and a book for her birthday. There were quite a few kids and their moms at the party. Moms

had frowned but all the kids loved the ball and scrambled over it.

Richa sat next to me and said, “My friend Varun Gajdhar says soccer is a

boys’ game. Is it?” “No

Richa. You may tell your friend there is no such thing as boys’ or men's games anymore. Women have taken over all the games.”

“Wow!” Richa ran off to announce the news. I

only knew Bandana slightly. Just exchanged ‘Hi’ and ‘How are you’ in the

elevators. She came to me in the party, “You must be getting very bored. Only

kids and women. And a few corporate type men here.”

“Don’t worry. I get along very well with kids.” “I

know. Eighty percent of Richa’s chatters are about you.”

Yogeshda had left shutting the door. I

needed a shower and breakfast to get rid of the hangover. My problem was that I

had to do everything for myself. My irregular schedule precluded having any

hired help. Lunch and dinners were mostly eaten outside, but breakfast was a

problem.

After shower, I checked in the fridge and found only half a loaf of

bread and two foil wrapped cubes of cheese. Milk, butter, egg, everything

was finished.

This fancy apartment was not mine. It belonged to my friend Shankar.

Before leaving for Dubai, he placed me in the flat, “See Runu, I have nobody

else. In case something happens, this will become yours…” I

said, “What? Don’t you know Dubai govt has banned dying? That’s why there is no

graveyard or crematorium there.”

Shankar shrugged, “Ya ya, go on, make jokes. Think I will ever be back

from Dubai? You will have to pay tax for this place, and then I will see you

making jokes. You know why I am putting this load on you. Just because I have

nobody…”

“Why? What happened to Somlata?”

“Aren’t you even ashamed to ask? You are the one who drove her away.”

“Not me. After introducing her you had whispered ‘Won’t I ever get

anybody sexier than this?’ and I said, “why not. There is always our Banalata.”

“Yes, you also said that she was drop dead gorgeous, big eyes, hair like

dark clouds, her face was like a goddess, she even smelled spicy, like cloves.

And you still haven’t introduced her.” “If

you weren’t so brainless you would have known Banalata couldn’t be any real

woman. She was poet Jibanananda’s Banalata Sen. Her hair is like the dark

nights of Bidisha and she never smelt of cloves. It was the cinnamon isle.

Those eyes are not just big, they are the nests for the homing birds.” “Of

course I know of Banalata Sen. I may not be as literate as you but you are no

surrealist either my friend. Just a third grade goalkeeper. Using a fictional

Banalata you drove away the real Somlata!”

“You drove her away. I just helped a little. And you don’t look like

you’ve been missing her at all, your trash can is filled with Neela,

Shubhashree, Payel, Parama, Bithi, who else is missing?”

“Nonsense! I don’t treat women like trash. I respect them. Relationships

can wear away of course… no, no point trying to make you understand. You still

have the picture of that skinny, dark, nose-ringed girl stuck on your heart

like a postage stamp. You are hopeless. Anyway consider this two thousand square

feet as yours. You are my only heir.” “On

what terms?”

“That you won’t understand.” Shankar sounded thoughtful.

“OK, Why are you getting so sentimental with Dubai? If you really don’t

want to go, don’t go.”

“You won’t get it. Shallow minded folks can never understand the deep

minded ones.”

Once when I dove for a ball I had hit my head on the goalpost and had a

concussion and heavy bleeding. I was told Shankar pleaded with the doctors to

make me well and offered whatever money was needed.

Occasionally he called from Dubai, “Still haven’t found anyone for

yourself? You are hopeless. You have an empty pad, a sexy goalkeeper image, use

them. The world moves fast my friend. Don’t stay stuck to the memories from

your puberty.”

“You better be careful in Dubai. Don’t mess around. Those guys have a

different culture.”

“You think Dubai hasn’t progressed? You have no idea. And I am not a

debauch, I am a romantic. The word ‘messing’ sounds dirty. I’m not like that…” I

had a crew cut so didn’t need to comb after shower. Still I liked to brush my

head after breakfast while standing on my south-facing balcony. There was a

street in front and a park beyond. After the rains, the trees were deep green.

Near the balcony was a bushy mango tree. A female crow had made a nest there

sometime ago. Every morning I saw her collecting straws, twigs, even plastic

clips, pieces of twines, refills of ballpoints etc. With infinite care, over

many days, she made her nest. It was

right in front of my balcony, between the second and the third floor. I didn’t

know when she laid the eggs but one morning I saw the nest full of eggs. Then

the chicks hatched. It was a pleasure to hear their thin chirps in the morning. But

I faced a small inconvenience. I usually dried my laundry on the balcony. Just

the usual pajamas, underwear, socks, shirt, handkerchief etc. The crow didn’t

like my activities. Whenever I stepped in the balcony she would guard the nest and charge at

me. Once when I was fixing the clip on the drying rope, she pecked at my hand.

I always told her that I was her friend and not a bad person. I don’t know how

much she understood but she never let her guard down. I tried to be her friends

but never managed it. One

day while putting the laundry out I saw the crow sitting quietly. No

aggression. I peered at the nest to see how the chicks were doing but found no

nest. I was surprised. The nest was there even yesterday. There was no storm

last night. What happened? I

tried to peer at the ground below. It was difficult to make out through the

bushy leaves, but looked like something was scattered on the ground. I felt

very sad, after all the care, the nestlings were almost ready to fledge, and

then in one instance, all was gone. I

don’t know what went though my head, I put on my shirt and went straight down.

The sweepers still hadn’t arrived, the nest was scattered all over under the

tree. The chicks were face down in the grass, dead. I wanted to cry.

Shambhu the security man was sitting on one side, I asked him, “How did

the nest fall? There was no storm last night.” “No

Sir, not storm, Mrs. Sen from second floor broke it.”

“Why?” I was surprised.

“The crow pecked at her daughter’s head. They got very scared.” “Did

the girl die?” I was gnashing my teeth. “Of

course not Sir,” Shambhu smiled, “ you don’t die just from pecking”.

“But the crow chicks died, didn’t they?” “I

don’t know Sir, Last night their maid used a stick to break the nest. The poor

crow was screaming a lot.”

Suddenly my tempers flared. When that happened the rage totally engulfed

me like a gasoline fire. I turned completely crazy. I balled my fists and ran

upstairs grinding my teeth; I could hear my hissing breaths. I didn’t know the

Sens but I started banging on their door and hitting the bell continuously.

From inside I could hear an alarmed female voice, “Who? Who is it?” A

young woman--not above twenty

five--opened the door. Wearing a nightie, hair messed up, terror in her

eyes. Looking at my enraged face she stepped back, “Oh my God!” My

voice got raspy and slurry when I got mad. That could sound very threatening.

“Why? Why did you break the crow’s nest?” “What do you mean? So what if I did?” “And what of the chicks? You killed them.

Why?” “Because the crows disturbed us. It pecked

at my daughter and drew blood.” “So what? She didn’t die. Did she? And for

that you killed the baby birds?” “Oh my! Such love for the crows! What will

you do? Beat me up?” A

thin girl in frock came running and hugged her mom, looking at me with surprise

in her eyes. Another young maid was staring at me too. Then a towel-clad man

came out of the bathroom and gave a manly roar, “What’s going on? Why are you

shouting at us?”

When I got very angry, I lost my speech, ran out of my breath. Except

for glaring with red-hot eyes, I could not do anything more. The

lady said, “Look at him! Just because we broke the crow’s nest last night, he

has come to yell at us. I thought he might even hit us!” Mr.

Sen had a robust physique. This got his danders up. “How dare you! So what if

we broke the nest? Is that an excuse for threatening my family?” I

was already flagging. I just mumbled, “It took her so long to make that nest… so

much trouble… the chicks were just born and now they are dead, in the grass…” I

was sure nobody was listening to me. I was just mumbling like a fool.

Seeing me calming down, and the neighboring apartment owners daring to

come out, Mr. Sen ratcheted his voice, “Coming to threaten us? What do you

think of yourself? We are all decent

folks here. If we call the police they will handcuff you straight to the jail.

Get out! Get out this instant!”

With my temper spent, I already felt like a deflated balloon. I also

realized that my behavior was most illogical and height of poor manners. I

could have stated my point much more politely. Suddenly something just went

wrong in my head.

There was no supporter for me among the crowd gathering outside. Someone

rasped, “This is that worthless goalkeeper fellow. Flaunts his muscles and

thinks we all should kowtow to him. How dare he enter and intimidate the ladies in

the house!” I was

well aware of the danger of being the victim of a crowd gone berserk. Years

ago, when I played in the second division, there was a vital match for

championship. In the last minute I had failed to stop a free kick. It was a

matter of pure bad luck but the spectators crowded in the field and beat me up

so bad that I had to stay in bed for a whole week. I

quietly went back to my own apartment and locked the door. I really felt like

kicking myself for my own stupidity. The

matter did not end there. The housing committee called an emergency meeting in

the community hall and called me to attend. Plenty of complaints and

accusations were made about me. An elderly man tried to object, “You all are

speaking against him, but he actually did have a reason, a humanitarian impulse

for reacting that way. The poor crow did lose its nest and chicks … think from

his point of view too… He was angry but his anger was justified.” One

fair, plump and aggressive lady in glasses got up, “I want to know if Mr.

Bharadwaj is a vegetarian. If not, I would ask him about his humanitarian

impulses when he enjoys his chicken, fish and goat dishes. You can’t call

yourself humanitarian by being sympathetic to one crow only.” I

did not say a word in that meeting. There was nothing for me to do but accept

complete defeat. At

the end, the secretary Milan Sarkar stood up, “This event is extremely

unfortunate, but we have never seen Mr. Bharadwaj behave improperly in any

other occasion. He is also a member of a well renowned soccer team. So, we

don’t want to take any punitive action against him. There may also be bad

publicity. As first offense, we are going to give him a warning only. Any more

such event in future will necessitate police reports. He is not a member of our

group or owner of the apartment. We hope he will control himself in future.” I

came back filled with bitterness and shame. I had even decided to leave the

place and go somewhere else. Let Shankar do whatever he wanted with his place.

I went to the club patron Damodardasji and asked him for any other available apartment. But

after a couple of days, when I was returning from my morning run, a young girl

ran to me and pulled me by my hand, “Hi, I’m Aditi Sen. And you are that

goalkeeper.”

Surprised I said, “Yes, but who are you?”

“Don’t you remember anything? I’m the one who got pecked by that crow.”

“What crow?”

“The crow that lost her kids. The mom crow.”

Still surprised I smiled, “Really?”

“Yes. Do you know I cried a lot because of the dead chicks.” “No!

I had no idea.”

“Come, my mom wants to see you.”

“Your mom?”

“Yes. There, she is sitting on that bench. We came here only to meet

you. Come. ” I

was confused. What was going on? Was it another dream? I had a habit of dreaming

weird dreams. The

lady sitting under the jacaranda tree stood up and greeted me. I didn’t

recognize her. That day I was so angry that I didn’t even notice what she

looked like. Now

she looked unbelievably beautiful. Slim, sweet, with large dreamy eyes dreamy eyes with long lashes. That sweet face looked not of this world. Could

someone this pretty ever be so cruel? “I

am Ranjana. We came here early in the morning just to see you.”

“You really needn’t have! You could’ve sent me a message and I would

have come.”

“But it is important. For last two days I’ve been wondering how to

explain it to you. Could you please sit down for a minute?” I

was still confused, but I sat down, a little bit away from her.

“You can’t imagine how embarrassing it is for me. You had to take so

much insult over such an insignificant matter. Yet you didn’t do anything

wrong. In fact you came to speak for a bereaved mother missing her offspring.

Even though a crow, she is still a mother after all.” I

felt very ill at ease, “How can you say that. I was most boorish that day,

walking in to your apartment. Not at all gentlemanly.”

Ranjana’s smile surpassed the dawn sunlight in beauty. Softly she said,

“Not at all boorish. Even my daughter cried her eyes out at the death of those

baby crows. Of course it was natural for you to get angry. I just reacted out

of surprise and a bit of fear at you suddenly storming my door. But you didn’t

insult me at all. Later on I thought about it, you only asked why I broke the

nest, that’s all. Then you were mumbling something about the trouble it took to

make the nest…something like that. More I thought, more I realized, I too am a

mother. I too have a child in my nest. What if someone came and hurt my nest

and baby…”

“Why! You are crying?” “It’s

nothing. I’ve been crying everyday. I didn’t attend the meeting. I knew they

would insult you and I couldn’t stand it. I told my husband to attend but I

also told him not to say anything against you.”

“And he agreed?”

“Yes. When I explained it all to him, he said to invite you for tea one

day.” I

burst out laughing, “This is exactly opposite of what I expected!” “I

can’t do the apology business though.”

“No, no! I should be the one to apologize.”

“Not at all. Never! I’ve been waiting just to tell you one more thing.”

“Yes?”

“That you are a very decent person.”

“And you too are a very decent lady.” “One last thing…hope our friendship will not end here.”

No,

no other crow nested in that mango tree. And I had become a good friend of

Ranjana’s family. They often invited me for tea and snacks. Even though I

didn’t care for junk snacks, I didn’t mind visiting and occasionally explained

the details of goalkeeping to Mr. Sugata Sen. He

would say, “So, you really don’t have much to do, right? I often see the

goalkeepers leaning against the goalpost or walking back and forth or chewing

blades of grass. The rest ten guys are the ones busy playing…” I

nodded seriously, “Exactly. The rule says one guy has to stand in front of those

wooden posts, so there is one. Like the boundary line around Sita, we too have

the penalty box around us. We can’t go outside of it. All the excitement,

running around, all the action happen outside that box. We goalies have nothing

to do with it. If you watch us you will see we are the loneliest players in the

whole field. Everybody forgets about us.”

“No, no. I didn’t mean it that way. Goalies often do spectacular saves,

block penalties.” “A

few. Most go unblocked. After all, scoring goals is the main action of the

game. Everybody wants to see a goal scored, not saved. Yes, occasional saves do

get a few claps but nothing compared to the cheers for a goal scored. That’s

why it is so hard for a goalkeeper to become a hero.” “How

can you say that? Lev Yasin, Gordon Banks…” “Go

on. You won’t find many more.” The

goalkeeper’s sorry fate had touched little Aditi. She climbed on my lap, hugged me, and

said, “Is that why you look so sad?” I

smiled at her serious face, “Not at all. When I am playing, I can see so many

butterflies flying around me, dragonflies jumping on the grass, caterpillars

crawling up the goalposts. I am friend to all of them. I never feel sad.”  Next:

Chapter 2

Translated by

Chhanda Chattopadhyay Bewtra. Chhanda (Chatterjee) Bewtra was born in Purulia, West Bengal but...

(more)

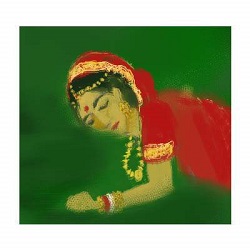

Illustrated by Nilanjana Basu. Curently based in California, Nilanjana has been regularly illstrating for Parabaas.

Click here to send your feedback

|