For Books by Sirshendu Mukhopadhyay and others, visit

The Parabaas Bookstore

For Bengali movies (with English subtitles), visit

The Parabaas Moviestore

|

Translated from the original Bangla novel

“Goalkeeper? What is the use of a goalkeeper, tell me. I can accept a doctor, an engineer, a singer, a dancer, even a poet may be; but what can a goalkeeper do for others?” “I don’t think any of us came to this world specifically to do something for others, in fact not even do anything for one’s own self. Doctors, engineers, singers, dancers, poets, novelists, none of them plan to do their jobs as good deeds for others.” “Perhaps. But the jobs they do ultimately do some good for others, don’t they? But amongst all these human needs and sufferings, where can we place a goalkeeper? Do you know of any contribution of a goalkeeper to the human civilization?” “Why are you expecting such high achievements from me? I never promised to be world famous. Most people like me just lead ordinary lives.” “Still, I just request you to think about it. Say you are a great goalkeeper. Perhaps Indian team may get a chance. Still, what’s the point? Nobody knows India’s name in the World Cup.” “Grandpa, You are having huge dreams about me! Look at my background. I am the son of an ordinary government worker. My talents are mediocre or even less. I don’t have any innate power of singing or writing poetry. My future is not expected to be bright. I am not expected to contribute anything to the progress of human civilization.” “I see, that means you are dead set on becoming a goalkeeper. But whatever I have seen so far of soccer, goalkeepers don’t seem to be of much importance. Anyway, it seems you would need a bike then, for commuting to the games. But what if it gets stolen when you leave it on the side and go to play?” “No fear. My friends will keep an eye on it. I am not the only one commuting. Lots of kids come on bikes from long distances. No chance of losing bikes.” “Hope you are right. How much did you say?” “Fifteen hundred, for a decent one.” “Dear me! In our times…” “Grandpa, this too is your time. Till you pass away, every thing is contemporary. And you know very well why costs increase.” “Still, fifteen hundred is a lot. By the way, hope you don’t take me for a miser.” “I do. You are a miser!” Grandpa smiled, “You know what miser means? It means conservative, protector of wealth. That in fact is for the good of the country.” “Miser suffers himself.” “Not at all. He just does not condone excessive spending. That’s all. Here, wait a minute. I will get you the money.” Grandpa brought the money and handed it to me, “Count it twice, always make sure.” “Do you ever make mistakes in counting money?” “To err is human. Why are you so lazy to count once more? It is not a good sign.” “I don’t enjoy counting money.” “Then you are in for hard times. You know what’s the problem with the women? They are too soft about their kids and grandkids. Not tough enough like the men.” “Are you talking about grandma?” “Yes, you are quite smart. You knew who to petition about the bike, didn’t you.” “True. I’ve noticed you don’t give in to pleadings. So I went to the person who has the upper hand.” “You think I am under my wife’s thumb? You are wrong. But women do have many ways to get even with us men.” “Grandpa, that’s not fair. My grandma is a simple sweet lady. Nothing diabolical about her.” “I didn’t say that. All I am saying is that women know about the psychological weaknesses of men; they don’t have to be taught. They know these things from birth.” “Whatever. My grandma is a great lady.” “Of course, she got you the money for your bike. Of course you will call her great now.” “And grandpa, I’ve noticed, you don’t really mind being called ‘hen pecked’.” “And you are extremely impudent and sassy. You have no manners.” “Why? Do you mind?” “Yes, but what’s the use. It wouldn’t change your casual attitude.” “No Sir. Once born with casual attitude, can never be changed to seriousness.” “And listen, when buying expensive stuff, don’t go for the superficial glitter. Buy well made items that will last long. Got it?” “Oh yes. Fancy bikes will never last on the rural roads where I have to ride.” “Also buy a chain and a lock.” “These bikes come with locks.” “Don’t depend on those. They are flimsy stuff.” “Grandpa, why are you so attached to material things? Haven’t you reached the age of detachment?” “Do you mean keeping the door open for the thief is the sign of detachment? There are many deeper meanings.” “Perhaps, but they are of no use to you. You put locks even on a cookie jar! How can you be detached if you are so into locks and keys?” “Impertinent! My greatest mistake has been to encourage you!” “What encouragement? Even for an ordinary bike I had to go to grandma. You call this encouragement?” This is how it was with my grandfather. He would yell and scream but they were always mixed with love and concern, so they didn’t hurt. He never bought anything fancy for himself, never indulged in food bought from outside. I was the first to feed him the famous kabiraji cutlet and chili chicken from Mahim’s shop. When he first saw it, he cried, “Oh my God! These are junk food!” I very politely told him that even Sumit Arora, the richest person in town, was a regular patron. Then grandpa said, ‘But Mahim is a thief! He charges too much!’ I told him, ‘Please taste it first. If you love it you would feel the price justified.’ When he tasted the chili chicken, his face brightened like the sunrise. Still he complained, ‘The taste is good but the price is still too high.’ I said, ‘Grandpa, worry kills enjoyment. Forget about the price and enjoy the food, otherwise you will miss the artistry of this chili chicken.” Grandpa smiled, ‘You talk too much. Anyway, let me keep some for your grandma.’ I too smiled, “Don’t worry, I already gave her a separate packet. This is all yours.’ Actually, this is not a story about my miser grandpa. It is the story of my bike. It was colored bright green. The pedal was high, just like all bikes. But as soon as I possessed it I felt a strong attachment for it. It was as if it had life, love, will power and loyalty. Every morning I woke up thinking about it. And I would rush out and touch it to make sure it was real, not a dream. Countless times I would stare at it adoringly. There were colorful rings inserted in the spokes of the wheels. They looked so pretty. I would brush them carefully with soft cloth. Any mud or dirt had to be rubbed off right away with a wet rag. The bike and I were one being. I had many dreams about that bike. Good dreams as well as bad ones. In case the ball hit my bike, I would park it carefully behind the goalpost net. So often I would turn and make sure it was still there. But anything mobile had to have the risk of accident. Minor dents and bends were frequent. Perhaps it bumped in a pothole and the mudguard got dented. Or it scraped along the steelwork of the gate and the color came off. My best friend Gulu once borrowed my bike to go to the street fair. When he returned the bike I noticed one spoke was broken. I used to physically suffer every trauma to my bike. My mom sometimes would say, “Runu, since you got your bike, you’ve forgotten me!” Then, one day the bike took me to the sky, among the clouds.

Nobody would be expected to recognize Shyamdas Lahiri’s house in Lamding. He lived in one of the countless little railway colonies. Two tiny rooms, a tiny porch like a mat and a tiny garden like a handkerchief. That was it. Unbelievably, it also contained a kitchen and a bathroom. And in that tiny space, all the activities of daily life—love, sex, pregnancy, babies crawling, children studying, guests being entertained, marital quarrels and make ups – everything took place. The rooms were permanently dark, and damp. The courtyard was always wet and slimy; there was a permanent scarcity of water. Yet Shyamdas Lahiri with his wife and three kids somehow managed in that cave like dark rooms. They fitted like nuts inside the shell. They looked sometimes so misplaced, as if they had just arrived and would leave in a minute. Actually it was not so. Sati was their oldest daughter. I had known her since she was a baby. She was an ordinary kid. She learnt her multiplication tables while rocking back and forth, like all other kids. She played hide and seek with other girls in the colony, bawled if scolded. The usual stuff. She did have two large surprised eyes. As if for her, there was no end to surprises. I never noticed her more than that. She was one of many similar girls.

Badyinath first started working with herbal medicines. He apparently knew the treatment of piles, asthma, dysentery, fever and madness! After doing medicine for a while, he suddenly turned to sharpening knives and scissors. Then he changed to astrology. When that failed, he became a welder of old utensils. After this he disappeared from Lamding for a while. It was told that he left for Sherpur and planned to be a singer there. He was perhaps training with an expert. But when he returned he was a magician! He would go around showing his tricks in the markets and fairs. After this, how or why he became a milkman was a mystery. As far as one could tell, he once chopped some timber for Mahim Ghosh and was paid with a male calf. With that he started his business of selling milk. Phatik babu once grabbed him, “How come you are selling milk? Where did you get a cow? You have only a male calf. Does that give milk?” “Badyinath gave a knowing smile, ”It’s complicated. You won’t understand.” “Oh yea? Scoundrel! What is there to understand?” “Everything has a reaction. Reactions can achieve so much. If everyone understood it, there would be no problems.” Badyinath told us about the wise bird Dasharath. That bird was apparently thousands and thousands of years old. Every year, on a certain day, he would come to roost on the old banyan tree in the Nilpur forest, by Dungri river. If someone found him that time, he could ask the wise bird any question and get his answer. Apparently last January, on a night of full moon, he told Razab Ali that this Kali era was almost over. There would be a huge flood that would drown everyone. Not a soul would survive. Then after the flood receded, there would be new creation. Everything would be new and different. Men would fly, crows would become like the showy peacocks, and the sand on Dungri’s shore would turn to gold dust. Even the poorest would afford breads fried in rich ghee, and a whole ilish fish would cost only a rupee! Once Badyinath came to change the washer of our tube well. While resting under the plum tree in the mid afternoon heat, he wiped his sweaty face and complained, “Well, you tell me, why don’t people believe me? Is it because I am a lefty? But that’s not my fault. Nobody can change how God has made me. Yet, because of that no one wants to believe anything I say. But honestly, I saw it with my own two eyes. But that evening, at Har Chakravarti’s house, when I told those important people, they all said I had smoked hashish. I swear by Goddess Kali, I’ve never even touched drugs.” “Why? We believe you.” “But you are little kids. Your beliefs don’t count. Wise, grown up men would have to believe. Then you can consider it a fact.” “People don’t believe lefties?” “Looks like that. That day I was offering old Mr. Thakur his sandals. I was doing it very nicely, but he got all mad at me. My fault, I was holding the sandals in my left hand! He yelled at me, called me names, ‘You used your left hand! You are worse than a monkey. You have no manners, no respect for the Brahmins. That’s why you will never amount to anything in your life.’ Then there was old Mrs. Dutta. After repairing her pots and pans, I put out my left hand to receive the change and she too insulted me no end. That’s why I am thinking; it must be my left hand. Yet, I saw it myself.” “What did you see Badyidada?” “Oh no. You would tremble in fear if tell you. It was unreal! Shyamdas babu’s courtyard had become very slippery. So the Mrs. ssked me to scrub it well, apparently nobody does it better than me. So, it was just last Friday, I was scrubbing away in the afternoon, and Sati was sitting on the porch cracking peanuts in the shells. When I started hosing down the yard, guess what I saw.” “What?” “I saw Sati eating peanuts with two hands and with two more hands she was combing her hair! First I thought I was hallucinating, but I rubbed my eyes and looked closely. Yes. She had four arms!” “Rubbish! Of course she has only two!” “Mortal eyes can only see two. She is not an ordinary girl. Gifted people could only see those extra arms on rare occasions. She saw me staring and quickly hid them somehow. I went straight to her and knelt on the floor, ‘Goddess! You are real!’ I said. And she ran indoor all embarrassed. I swear it by Goddess Kali!” After hearing this story I went straight to Shyamdas babu’s house, “Auntie, where is Sati?” “She just left to get a knitting pattern from Hena. She will be back soon. Why?” “Badyinath said Sati has four arms?” Auntie burst out laughing, “That crazy man! I hear he smokes hashish under that banyan tree. That’s how he sees fairies, demons, even Gods and Goddesses some times. What a riot! That day that grown man was on the floor at Sati’s feet, crying and calling her Goddess. Poor Sati was so embarrassed. That’s why you’ve come? You are crazy too. There. She is back. Go see how many arms she has.” I almost didn’t recognize the girl who entered. She was startled to see me. This wasn’t Sati. Who was this vision? There was a strange ray of light on that dark and damp yard. The air shivered ever so slightly. Even that small house looked different. Not as dark and gloomy. “Hey Sati, look who has come to check your extra arms.” Sati shyly covered her face and ran inside. Sati’s mother said, “She is embarrassed. Badyinath created such a scene. Let him come again, I will have to give him a lecture.” Every human has some small or large disasters. Some are hidden well. Nobody can see or rescue them. It became apparent in a few days that the disaster struck on both sides, not just one. That moldy house of Shyamdas started attracting me like a magnet. But lest it looked obvious, I used to visit them every few days only. Sati would never appear in front of me. But I could catch glimpses of an arm with bangles, may be an eye, a curl of her hair, perhaps parts of her sari or frock. Amazing. Those fleeting moments meant so much to me. And thus we got over our puberty, with only vague hints and glimpses. I grew beard and moustache. Suddenly I also grew tall. There were no cell phones in those days, so I got love letters from the girls. No, never from Sati Lahiri. She knew she didn’t need to write any love letter. She could send her love to me like the wafting scent of a flower or the smell of an incense. I would often return from a match with injuries. My mom was my physician. She would warm lime paste and turmeric mix and bandage my wound with a paan leaf. That evening I was lying down with lime turmeric paste on my sprained ankle. I could hear the noise from indoor. There was Shani puja going on and all the women and children of the neighborhood had come to attend. Suddenly I saw Sati’s younger sister Priti in my room, looking around. “Hey. What’s up?” “This is your room?” “Yes.” “Aren’t you scared?” “Scared about what?” “I’m very scared of sleeping alone.” “Girls are such scaredy cats!” “You bought a new bike? It is so pretty.” “You want to ride? I can teach you.” “How? It’s a boy’s bike.” “What would you wear when you grow up? Jeans or sari?” Priti thought for a moment, “Jeans.” “Then you should have no problem riding men’s bike.” “But it is so high. How would I climb on it?” “You won’t remain a little girl for ever.” “OK. Then I will learn. But before that would you seat me in front and take me for a ride?” “Sure.” Priti sat on my bed and touched my bandaged foot, “Is it hurting a lot?” “Awful. But injury happens in sports.” “Then why play?” “You don’t?” “No, not me, nor my sister. Only my brother plays.” “Your sister can never play. She is too shy.” Priti was surprised, “My sister? She isn’t shy at all!” “No?” “Absolutely not. Everybody knows she is very smart. She is only shy with you. She always hides when you come to visit.” “But why? Do you know?” “No. I once asked her, ‘You are so smart, what happens to you in front of Runuda?’ She became serious and told me that I wouldn’t understand it.” One moonlit night that bike caused an incident. That evening Shyamdasbabu returned home from work with chest pain and breathing difficulty. The railway physician came over, examined for a long time and said, “Move him to hospital. I think it is a heart attack.” This was big news in a small town. People rushed out to help. He was taken to the hospital in an ambulance. Beside Badyinath, there was one more person who knew that Sati wasn’t an ordinary girl. That person was her father Shyamdas himself. He was absolutely sure of it and perhaps that is why Sati too was more attached to him. And that’s why she was stunned at this sudden illness. Railway hospital moved at a snail’s pace. It was late at night when all the tests were done. Ultimately it was decided not to be too serious. The gas in abdomen had exacerbated the pain. They would keep him under observation. They would continue the oxygen and the drip. Hearing that the patient was not serious, the crowd thinned. Lahiri auntie saw me standing outside near the hospital gate and came to me, “Runu dear, I can’t move Sati from his bedside. I also have left the other two at home. Got to go feed them something…” “You go home auntie. I’ll stay here and take care of things.” “Escort Sati home, please. It is getting late and dark. She may not be able to go home alone.” “It’s OK.” No, nothing was OK that night. There was a universal conspiracy going on around us. The air was filled with all kinds of whisperings. Even the moon looked overly dramatic that night. Could a weather report be ever so perfect? And how come I didn’t even get hurt in the match that day. It was totally natural that I would stand there waiting for her. As if it was the expected thing. If needed I would stand all night. Around eleven thirty, when everything had closed up, she came out quietly. She didn’t utter a word, just came to me and stood there looking down. As if now she wanted my help. I said, “Will you manage on the bike?” Very softly, “I would rather walk.” “You want to walk? It is very late and dark too. Can’t you climb on the rod in front?” She nodded, “Yes.” Perhaps she never rode a bike. I asked worriedly, “Are you sure? What if you fall…” “I won’t, someone will catch me.” That one sentence opened the floodgate of feelings. My heart was singing, the bells were ringing, and I could hear the drums, the cheering all around us. Sati stared in front all the time. Her open hair caressed my face and my eyes. That night the angels lined up along the road to see an incomparable sight. A celestial bird flew above us to show us the way. Butterflies and fairies danced around us. And for a little while, that rough potholed road became smooth as glass. And that sentence, “I won’t fall, someone will catch me.” Even today I do not know a deeper sentence of love.

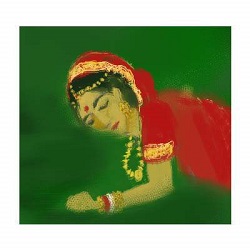

Occasionally some magician turns everything upside down in our lives. They are not the magicians of the stages. Their magic is different. Nandan Sanyal was one of them. He was the new English professor in our college. His first magic was his looks. Fair complexion, thick, dark curly hair, clear eyes, perfect features, and very attractive voice. He could sing well and his face shone with intelligence and smartness. I thought it was too much. One didn’t need so many good qualities. Even a few less would be enough to get by. But that was not all for Nandan. He could also teach well, had unique ability to make the students listen to him; he could explain dramas and poetry beautifully. In only a few days he hypnotized the whole town. Everyone became his fan. Everyone was talking about him. I tried hard to find a flaw in him. I felt perhaps his beauty had diminished his virility somewhat. He was tall and slim, but not heavily muscular. But then everyone didn’t need to be a wrestler. Nandan had just graduated and joined work. He was very young. As a result all the girls lined up behind him like the pied piper of Hamelin. It was hard to compete with a man so perfect in all ways. This was his magic. That was how people like him always managed to get the power and prestige with ease. Some folks worried about the women. Such overly attractive man could easily charm and mess with any married or unmarried girl. But Nandan didn’t show any such inclination. He freely mixed with women, but never crossed the line of decency. Perhaps people like him were so used to adoration early on from both sexes that in adulthood they were already sated. There was no reason for a barely passing student to envy the top candidate. The very high and the very low seldom get any chance to interact. So few were envious of Nandan. Except myself. Why did I envy him? I do not know. It was a mystery to me. But I was. There was no competition between us but I would say to myself, “Can you save goals like me? Can you dive and block a powerful shot? Can you save a penalty? Not a chance!” There was no sense in such envy. Why would Nandan Sanyal dive to save a goal? Goalkeeping was not his job, perhaps he didn’t even know about it. When I first met him, my friends introduced me, “Sir, this is Runu. Our goalkeeper. Plays in the district.” He was very surprised, “Goalkeeper? You are a goalkeeper?” I thought perhaps he didn’t understand goalkeeping, but next moment he said, “That’s fantastic!” And looking at his face I felt perhaps goalkeeping was the world’s worst kind of job. For no reason at all, thinking about Nandan Sanyal gave me heartburn. Sati used to learn music with an old teacher. I had never heard her sing. But I remember one year there was a recital staged by the railway colony people after Puja. They spent some money and invited two celebrities from Kolkata. Everyone was excited. On the day before the recital, Priti came to me, “Runuda, I need to ask you something very secret.” I smiled, “Since when did you start having secrets?” “I do. I have to whisper it in your ear.” “Why? There is nobody in the room except us.” “OK then. Here it is. You mustn’t attend the recital tomorrow.” “Why on earth not?” “My sister has asked me to tell you.” My heart missed a beat, “What did she say?” “That you must never go to the recital.” “What would happen if I do?” I was surprised. “She said, ‘If he comes, I won’t be able to sing’.” I felt a strange sensation in my body. If I went, she wouldn’t be able to sing! I was such a special person for her that seeing me she would become nervous, her heart would beat faster, her throat would dry up! Then I must never go there, even in a crowd of hundreds. “OK. Tell her I wouldn’t go.” Next day the entire household went to the function. All my friends tried to take me along but I refused with the excuse of an injury in my leg and spent the evening dreaming about the whole incident. I felt very touched. I was an important person to one person at least in this world! It was a very big deal. Next evening Priti came again to whisper in my ear, “Sister said ‘Thank you’.” I smiled, “How did it go?” “Wonderful. Singing, dance drama, comedy.” That winter, I saw Nandan in front of Shyamdas Lahiri’s house, chatting with auntie. Nandan was saying, “Yes, auntie, I will come occasionally and help them with their English. Don’t worry.” Later I asked auntie, “Is Sir going to do private tuition here?” “Oh no! We can’t afford such a top class professor. But he met Sati in that recital and liked her singing. Since then he drops by for tea. So I asked if he would help Priti and Bablu a little, they are very weak in English. And he agreed immediately. What a nice boy. Doesn’t even want any money. You know we are also same caste, Barendra.” “So what, auntie?” “No, nothing. Just mentioned, that’s all.” But the caste issue got stuck in my brain. What was the big deal? Being same Barendra caste made him more desirable to the family? Also other thoughts tailgated in my mind. Why was Nandan Sanyal so keen to visit them? Just to teach English or was there some other plan too. I had once asked Priti, “Why does Sir Nandan come to your house?” “He just chats, sings songs, and teaches us English.” “Everyday?” “Oh no. Two or three days a week only.” I was seriously worried. Of all the houses and all the families in this town, Nandan Sanyal had to choose Shyamdas Lahiri’s tiny dark house? Sometimes I would cruise by their house on my bike. I couldn’t understand what was going on inside, what cryptic message was getting transmitted from one to the other. Those were the days of intense agony.  Next:

Chapter 4

Translated by

Chhanda Chattopadhyay Bewtra. Chhanda (Chatterjee) Bewtra was born in Purulia, West Bengal but...

(more)

Illustrated by Nilanjana Basu. Curently based in California, Nilanjana has been regularly illustrating for Parabaas.

|