-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Satyajit Ray | Essay

Share -

Translating Between Media: Rabindranath Tagore and Satyajit Ray : Clinton B. Seely

Keynote Address Delivered at the Twelveth Annual Tagore Festival

Saturday, 21st October, 2000

University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, IL

Tagore, in terracotta (artist unknown, obtained from the Paus melaa, Santiniketan); computer art (by Nilanjana Basu), and in cut-out (by Supurna Sinha) In a sense, all expression, particularly what we call artistic expression, is translation. The artist translates her or his ideas into a verbal expression, in the case of the writer; or into a visual, verbal, and auditory expression, in the case of the filmmaker; or into a visual and possibly tactile expression, in the case of the sculptor; or into an auditory and maybe verbal expression, in the case of the musical composer -- and so on and so forth. I could mention other specific sorts of artists -- painters, playwrights, and potters, for instance -- but I think my point is clear: all art, though we like to think of it as an act of creating, is from one perspective an act of translating. It is the act of translating an idea into some medium, that is to say, into some perceptible form. If artistic expression, in the terms just described, is translation, then the activity that we commonsensically refer to as translation is, or at least can be called with equal validity, an act of artistic creation.

I am emphasizing the creative aspect of translation, for the very reason that current dictionary definitions do not. Three meanings for "translate" in a modern English-language dictionary are the following: (1) to turn from one language into another; (2) to change the form, condition, or nature of; and (3) to explain in simpler terms. The last of these definitions, "to explain in simpler terms," I shall ignore, for that meaning does not pertain at all to my use of the word "translating" in the title of this talk. The first definition, "to turn from one language into another," is possibly the most obvious rendering of the word "translating" and the first to come to mind. It is the sort of translating that Rabindranath Tagore himself did in 1912 with some of his own Bengali poetry in order to produce the volume in English known as Gitanjali, for which, as we all are well aware, he received the Nobel prize for literature the following year. It is, however, the second definition of translate, "to change the form, condition, or nature of," that I mean to evoke by my title. Again, I can turn to Tagore to illustrate this second definition of the word translate. Tagore published his drama Citrangada, titled for the central female character, in 1892; more than four decades later, he translated -- that is to say, changed the form, condition, or nature of -- Citrangada, his play, into Citrangada, his dance-drama. One could argue that Tagore's original drama Citrangada is, in fact, a translation of -- a changed form of -- the tale found in the Mahabharata whence comes, quite obviously, at least some of the inspiration for Tagore's drama. These are all, in one way or another, examples of translation, in the second definition of that word. That is to say, the subsequent work changes the form of the precursor that it is translating. All of the above-mentioned translations, moreover, are in some sense original artistic creations, just as all of the them are in some sense derivative. A further case in point is Tagore's short story Nastanir (The Fouled Nest, published in 1901) and Ray's translation of it into the film Charulata, completed in 1964, released in 1965.

I would like to consider today three aspects of these last two works, Tagore's and Ray's: first, the autobiographical/biographical nature of both and how Ray's translation forces us to acknowledge that fact; second, how Ray, the creative artist, translates Tagore's words into images, some with accompanying words, some without; and third, the manner in which both the short story and the film function as a Tagore apologia. More on each of these later.

Let me reprise very briefly the subject matter of Tagore's story for those non- Bengalis here who might not know it. It tells of Charulata, a woman in her early twenties who had been married as a child to a husband, Bhupati by name, some ten to fifteen years her senior. She grew to maturity in her husband's household, benignly ignored by him. Bhupati has his own interests, in fact one all-consuming interest, that of publishing an English-language political newspaper in colonial Calcutta. He seemed almost oblivious to the presence of a wife who has, at the time of the story begins, become a mature young woman. Also living in that household, while he attends college in the city, is Amal, cousin-brother of Bhupati and someone with aspirations of becoming a writer. Charu and Amal are close in age, closer by far than Charu and her husband. The two near- contemporaries bond in many ways, like brother and sister, like intellectual equals, like young adults excited and at times overwhelmed by the literary culture of Calcutta of that day. Charu, confined by the then current mores to the house, albeit a very richly furnished upper-class house, gets to live in part vicariously through her brother-in-law who brings to her life some of the thrill of a fuller intellectual outside world. Eventually, it becomes evident to Amal that this relationship with his sister-in-law may have crossed the emotional boundary into forbidden territory. Amal withdraws; Charu is heartbroken, devastated; Bhupati feels sadly betrayed. End of story.

Shifting from literature to life, I shall similarly reprise as briefly and selectively events in the Tagore household seemingly pertinent to Tagore's tale. Kadambari Devi came into the Tagore extended family at a young age, as the child bride of Jyotirindranath Tagore, one of Rabindranath's elder brothers. Rabindranath was the fourteenth and youngest living child of his parents. Jyotirindranath was thirteen years his senior. Concerning Kadambari Devi and Rabindranath, who was close to her in age, Tagore's most authoritative biographer, Probhat Kumar Mukhopadhyay, writes: "He had been her playmate and companion ever since her marriage." [1] On December 9th of 1883 at the age of 22 Tagore himself was married to a girl of 11, whom he renamed Mrinalini and with whom he had five children. One of them, Rathindranath, as this Tagore Festival audience is well aware, studied at the University of Illinois. Tagore and wife Mrinalini lived happily together until her premature death in 1902. In the words of biographer Mukhopadhyay, Tagore's marriage at the end of 1883 had been "sudden and unexpected." [2] In late April of the following year, slightly more than four months after his wedding, Kadambari Devi committed suicide. Why she took her own life, if known, has never been made public. Biographer Mukhopadhyay writes of Kadambari Devi's death: "The reasons are shrouded in mystery. But that there was some family misunderstanding, it cannot be doubted." [3] Krishna Kripalani -- a relative of Tagore's; he married Tagore's granddaughter -- tells us bluntly in his own biography of Tagore not to speculate on the cause of the suicide.

Kadambari Devi

That Kadambari Devi's death was profoundly felt by Tagore can be readily established through Tagore's own words. To a young Amiya Chakravarty of about 16, who would a decade or so later become Tagore's literary secretary for a period of time, Tagore wrote in 1917, and I translate:

Rabindranath, 1882

Once, when I was about your age, I suffered a devastating sorrow, similar to yours now. A very close relative of mine committed suicide, and she had been my life's total support, right from childhood onward. And so with her unexpected death it was as if the earth itself receded from beneath my feet, as though the skies above me all went dark. My universe turned empty, my zest for life departed. [4]In the reminiscences entitled Jiban-smriti (1911-12), Tagore wrote in a similar vein. His mother's death, as it occurred when he was quite young, did not affect him strongly, he tells us. Part of the reason for this was Kadambari Devi, who immediately assumed the role of surrogate maternal figure. Kadambari was herself a young girl at this time and, as Tagore's biographer informed us above, Tagore's playmate. It is her passing that traumatizes him or, as he put it, "It was my acquaintance with death at the age of 24 that left a permanent impression on me." [5] Kadambari Devi's death is that to which Tagore refers here, though he was actually 22 at the time, just a couple of weeks shy of his 23rd birthday, not 24.

There are a number of poems by Tagore that speak to or about the deceased Kadambari Devi, as the editor of Tagore's collected works calls to our attention. Shortly after her death, Tagore in his mid-twenties calls out to her. I'll read only bits and pieces of this poem entitled "Where" (kothay):

Alas, where will you go!

In that endless, unknown land, and you alone, all alone,

How will you find your way!

Alas, where will you go![6]

None of us will be there for you

None of us to chat and talk to

We shall sit here and shall weep,

Gazing off into the void, we'll call to you;

Amidst that vast, that lonely place perhaps our lamentations

You might chance to hear from time to time,

Alas, where will you go!And then some 30 plus years later, Tagore composed the following equally poignant piece. I shall first read the entire translation into English, untitled, that Tagore himself made.

I was walking along a path overgrown with grass, when suddenly I heard from some one behind, "See if you know me?"

I turned round and looked at her and said, "I cannot remember your name."

She said, "I am that first great Sorrow whom you met when you were young."

Her eyes looked like a morning whose dew is still in the air.

I stood silent for some time till I said, "Have you lost all the great burden of your tears?"

She smiled and said nothing. I felt that her tears had had time to learn the language of smiles.

"Once you said," she whispered, "that you would cherish your grief for ever."

I blushed and said, "Yes, but years have passed and I forget."

Then I took her hand in mine and said, "But you have changed."

"What was sorrow once has now become peace," she said. [7]The Bengali original was published in 1919 in the magazine Sabuj Patra and then in the volume called Lipika (1922), which is a collection of prose poems or in some cases actually short, short stories. The Lipika version of the piece corresponding to what I just read is entitled "First Sorrow" (pratham sok). There are a number of lines in the middle of the original work left out of Tagore's English poem. In fact, nearly half of the original has been omitted. I cite here the entire Bengali poem, [8] as printed in Tagore's collected works, with an accompanying translation, his English in italic type and my rendering of the elided passages in plain type.

I was walking along a path overgrown with grass, when suddenly I heard from some one behind, "See if you know me?"

I turned round and looked at her and said, "I cannot remember your name."

She said, "I am that first great Sorrow whom you met when you were young (twenty-five)."

Her eyes looked like a morning whose dew is still in the air.

I stood silent for some time till I said, "Have you lost all the great burden of your tears?"

She smiled and said nothing. I felt that her tears had had time to learn the language of smiles.

I asked, "Still today you've kept with you that youth of mine when I was twenty-five?"

Said she, "Here, just look, my garland."

I could see, not a petal had fallen from the garland of that springtime back then.

I said, "Mine has become completely withered, but my youth at twenty- five is still this day as fresh as ever, hanging there about your neck.

Slowly, she took off that garland, placing it around my neck. "Once you said," she whispered, "that you would cherish your grief for ever." I blushed and said, "Yes, but years have passed and I forget."

She added, "He who is the bridegroom of my inner thoughts, he had not forgotten. Since then, I've sat here secretly beneath the shadows. Accept me now."

Then I took her hand in mine and said, "But you have changed."

"What was sorrow once has now become peace," she said.He speaks in the original of his youth of age 25, and asks whether she has kept that youth of his with her. She replies by calling attention to the garland around her neck, a garland that is as fresh now as it was back then. His, however, has dried up in the intervening years. She then takes the still fresh garland from her neck and places it around his.

Above, I called your attention to the fact that Tagore says he was 24 when his sister-in-law died when in truth he was 22 going on 23. Here, in a piece written in 1919, almost a decade after his reminiscences Jiban smriti, he specifies 25 as his age when Kadambari Devi committed suicide. There are two easy explanations for these deviant numbers. One is to reiterate the adage that to err is human. The other is to remind ourselves of the various calendric systems current then and now in Bengal and of the fact that birth certificates there are of fairly recent origin.

Flower garlands, mention of which is not found in Tagore's English translation, are used in many ways in Bengali society. They are offered as a sign of respect, to a dignitary, for instance. They are also exchanged by a bride and bridegroom during a Hindu wedding ceremony. The other person in this poem, the one who is not the narrator, when she takes the garland from her own neck and places it around the neck of the narrator, adds, "Don't you remember? You said then you longed not for solace but for sorrow." Our narrator, chagrined, concedes that he had once uttered those words, but that with time, he had forgotten. And she replies, "He who is the bridegroom of my inner thoughts, he had not forgotten. Since then, I've sat here secretly beneath the shadows. Accept me now."

Another of the Lipika collections, called "Seventeen Years" in the Bengali but is untitled in Tagore's translation, begins as follows:

The name she called me by, like a flourishing jasmine, covered the whole seventeen years of our love. With its sound mingled the quiver of the light through the leaves, the scent of the grass in the rainy night, and the sad silence of the last hour of many an idle day.

Not the work of God alone was he who answered to that name; she created him again for herself during those seventeen swift years. [9]Who was this woman who Tagore, in his own English in 1919, says "created him again for herself during those seventeen swift years," the years between when she entered the Tagore household as Jyotirindranath's child bride and 1884, when she took her life? A partial answer to that question is to be found in Tagore's short story "The Fouled Nest," which may be read as a histoire a clef, a translation from real life, a story keyed into real-life characters and real-life events. There are, of course, incongruencies between the fictionalized rendering and the actual characters and events to which the work of fiction supposedly conforms. The names are changed, quite obviously. Familial relationships are altered somewhat. Bhupati, who would correspond to Jyotirindranath, and Amal, who would be the Rabindranath counterpart, are cousins in "The Fouled Nest," not brothers as they were in real life. Other discrepancies are there, no doubt, but a fundamental question to be asked is this: Though we may do so, why should we at all read "The Fouled Nest" as a histoire a clef corresponding to events in the lives of Jyotirindranath, Rabindranath, and Kadambari Devi? The simplest answer to the question is that Ray in his film Charulata has done so. Once one has seen the film, Tagore's short story perforce takes on that deeper, richer meaning. What, then, is the justification for Ray's translating of Tagore's story thus?

Marie Seton, in her 1971 book on Satyajit Ray entitled 'Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray', writes that Ray, when he was doing research on Tagore during the later 1950s in preparation for turning "The Fouled Nest" into film, came across, as Seton puts it, "Tagore's marginal notations linking the name of Rabindranath's sister-in-law . . . with that of Charu, the novel's central character." [10] Seton adds parenthetically that Bengal believed the sister-in-law "committed suicide following 'Rabi's' marriage." [11] Andrew Robinson, in his 1989 book called 'Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye', reiterates Seton's finding and elaborates, stating that Ray had seen "a very early manuscript of Nastanirh with marginalia which refer many times to Hecate [hek-it]," Tagore's nickname, we are told, for Kadambari Devi. [12] Hecate, the name of Greek goddess identified with several other goddesses including Artemis, and thereby associated with the moon but also with Persephone, and thus connected with the netherworld, witchcraft, and magic. It is this latter aspect of that goddess which informs the several appearances of the Hecate character in Shakespeare's dramas. The nickname speaks to a close and teasing relationship Tagore had with his sister-in-law; it also speaks to erudition, on Tagore's part, certainly. The manuscript Ray saw, moreover, had a sketch of Kadambari Devi in profile, Ray told Robinson. It convinced Ray that Tagore's sister-in-law was on his mind as he wrote his story "The Fouled Nest." [13] Consequently, Ray sets his translation of Tagore's story at a time, 1879-80, when the Tagore character, named Amal in the story, could have been a youthful college student, several years prior to Tagore's actual marriage in 1883. With that 1880s setting, Ray has reaffirmed the idea that "The Fouled Nest" should indeed be read as a histoire a clef with the corresponding real-life characters being Tagore himself, his sister-in-law, and her husband, his brother. And, I suggest, knowing what we know of the fate of Kadambari Devi, the tale in both its written and film version becomes, if read as a histoire a clef, that much more powerful.

Before moving on to my second concern in this talk, that is to say, how Ray translates Tagore's words into images, let me try to put into my own words not just what happens but what this tale is all about. Tagore's "The Fouled Nest" is on one level a tale of a marriage compromised. It is a tale of the metaphorical nest or sanctuary, supposedly provided by marriage, fouled from within by both of the marriage partners, each in her and his own way. It is about relationships, general human relationships and specifically relationships in the context of Calcutta of the 1880s in an upper-class Bengali extended family household. It is about communication between human beings and the failure of human beings to communicate. It is about an exceptionally talented -- we may even say gifted -- woman starved for both emotional and intellectual companionship. It is about her stifled creativity, partly what we might call maternal, for she was childless, and partly what we must recognize as artistic, since we are shown her to be superior to Amal in her one and only literary composition.

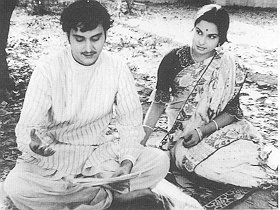

Amal and Charu, in a scene from Charulata The relationship explored in "The Fouled Nest" is that of bouthan and thakurpo, to use the Bengali terms of address, which correspond to "elder brother's wife" and "husband's younger brother." The term of reference for the thakurpo is debar. Charu is Amal's bouthan, also called boudi in more modern Bengali; he is her thakurpo or debar. The bouthan-thakurpo relationship is completely sanctioned in Hindu Bengali society and is considered exceptionally sweet. Whereas a married woman in a traditional household may not be allowed to appear before other men in the family, and certainly not before strangers, she can mix freely with her thakurpo and is encouraged to do so. But such a relationship is fraught with danger. There are three rather basic categories of love in Bengali, represented by the three words sneha, bhalobasa, and prem. The first, sneha, designates the sort of love a parent feels for a child. The third, prem, speaks to amorous love, of a romantic nature, unless specifically couched in terms of love for a deity. Bhalobasa is the least specific of the three terms and can mean "love" in both the sneha and the prem sense and also in a more generic meaning of strong positive emotions. The sanctioned bouthan-thakurpo relationship should be one of sneha, particularly with respect to the emotions felt by the woman, the bouthan, for her husband's younger brother. The danger with this relationship is that it might evolve out of sneha and into prem, which is what happens to Charu in "The Fouled Nest." Neither Charu nor Amal, and certainly not Bhupati, realizes that the limits of sneha have, unbeknownst to them, been transgressed. There is irony throughout, and particularly leading up to here. Charu, who supposedly can "see" what is amiss in the relationship between Manda, who is her brother's wife, and Amal, cannot in fact see at all. Charu and Amal do not see their own relationship for what it has become. They don't see it, that is, until the moment when awareness comes to Amal, but to Amal only at first. He knows something is terribly wrong with his and Charu's relationship. It is his epiphany and the turning point in the story.

Leading up to this turning point are several crises within family, all impinging upon Bhupati most directly. Two of these are conveyed by Tagore through similes, and similes of a similar sort, having to do with the presence of terra firma to stand upon or the lack thereof. In the first, Bhupati finds out that Umapati, Charu's brother, has been embezzling from him. When comforted by Bhupati, Umapati vows to repay every pice, swearing upon his own name. In the translation by Mary M. Lago and Supriya Sen, we read of Bhupati's reaction:

Bhupati was not consoled by the inviolability of Umapati's name. He was not so much offended by the loss of the money, but this sudden revelation of treachery made him feel as if he had stepped from his room into a void. [14]In order to save his beloved newspaper, in jeopardy due to Umapati's deceit, Bhupati goes to an acquaintance named Motilal to whom he had lent a considerable amount of money some time ago. Bhupati now asks for it back. Motilal at first feigns no recollection of the loan, then a moment later declares that it was long since canceled. Bhupati reacts as follows:

To Bhupati's eyes everything seemed to undergo a complete change. His body prickled with terror when he saw that aspect of the world which had just been unmasked. Like a frightened man who, in the face of a flash flood, looks for the highest ground and runs toward it, Bhupati went swiftly from the fear-ridden outer world to the inner rooms of his own house. He said to himself, "Whatever else happens, Charu won't deceive me." [15]But of course, Charu does deceive him, in a relatively small way at this particular moment. She immediately, almost involuntarily, hides from him the notebook in which she has been writing. The notebook represents that little literary world she seeks to share with only Amal. Tagore comments:

When a heart already aches, a small blow causes severe pain. Bhupati was hurt when Charu hid her writing with such unnecessary speed as soon as she saw him. [16]Shortly thereafter Amal returns to the house. He encounters Bhupati. Amal notes that his elder cousin-brother does not look well, that Bhupati is choked with emotions and on the verge of tears. Amal asks Charu what is wrong. She replies that she had not noticed a thing and then eagerly proceeds to try to engage Amal in matters pertaining to their private world of literature. It is then that Amal has his epiphany.

In Tagore's text, this epiphany gets conveyed by means of a moderately extended simile. That extended simile, though not developed at length, does, as any extended simile will do, suspend the forward motion of the narrative momentarily. The reader is transported out of the immediate action of the main narrative and into the realm of the mini narrative digression provided by the content of the extended simile. That momentary suspension of the main action -- suspended while the contents of the extended simile are being narrated -- lend gravity to the action so arrested. It is as though that suspended moment lasts longer, and therefore is more worth attention, both by the character in the narrative and by the reader. That moment in Tagore's narrative is as follows:

Charu, in a scene from Charulata

Charu had made up her mind that Amal would demand to see her new piece. She even turned its pages a little. But Amal looked very sharply at her face for a moment -- who knows what he thought, what he understood? Startled, he stood up. When clouds suddenly lift on a mountain road, the traveler is alarmed to find himself on the verge of stepping off into a ravine a thousand feet deep. Amal left the room without a word.

Charu could not fathom his unprecedented behavior.[17]We are at this point less than two-thirds of the way through Tagore's short story. Amal will appear only twice more in the remaining one-third plus, and then only with Bhupati present, never in Charu's company alone except very briefly and quite formally to bid farewell to his sister-in-law. Thereupon Amal leaves the household altogether and for good.

What Tagore conveys to us through the words of his omniscient -- but interestingly not completely omniscient -- narrator, telling us that Amal's feelings are like that of a traveler upon a mountain path with one foot extended over a deep ravine, Satyajit Ray shows us in a scene wherein words give context to what Amal is thinking. Preceding this scene, Bhupati has found out from his newsprint supplier that Umapati has been cheating him. The Motilal character in Tagore's short story disappears completely from Ray's film. But Bhupati is no less despondent in Ray's depiction of him. At the epiphanic moment, when Amal has some sort of realization, Ray shows us a shot Amal, then of Charu. The camera is positioned as though over Amal's shoulder. We the viewers are, as it were, seeing Charu through Amal's eyes. She appears at a distance, then disappears from our and Amal's view. Her glance had been cast in the direction of Amal, and she seemed -- and in fact was -- completely unaware of the calamity that Bhupati has so recently learned befell him. The simile of the traveler stepping off a mountain path into the ravine is completely missing in Ray's translation. Instead, Ray has Bhupati speak the words Tagore wrote to Amiya Chakravarty, cited above, about the earth receding from his feet. Tagore meant to convey with that conceit the emotions he felt after Kadambari Devi's death. Ray has Bhupati use that same image to express Bhupati's feelings after learning that Charu's brother has deceived him. The nature of that verbal image is, of course, comparable to the epiphanic extended simile in Tagore's short story. The verbal message, spoken by Bhupati, is not lost on Amal. The facial expression of Soumitra Chatterjee, the actor, conveys all we need to know of Amal's state of mind and, in fact, maybe more than Tagore's words can say. Like Tagore's original, Ray's translation has Amal appear but briefly after this, even more briefly than Tagore allows him to stay. Amal then vanishes during the rest of the film, except for his voice reading his own,.

Finally, my third point -- that Tagore's short story is an apologia. And, just so there is no confusion as to what I mean by the term apologia, let me be precise. I use apologia not in its meaning of an expression of regret for an action committed but in its primary meaning of a statement offered in defense, a statement intended to exonerate. By this short story, so sensitively written, so skillfully crafted, Tagore is telling the world, and emphasizing to himself, that he was not to blame, that the outcome depicted in the story was not his fault. This work of fiction, I suggest, can be seen as an exorcism of sorts. It is an attempt to assuage the pain he felt nearly two decades earlier and no doubt still feels at the beginning of the 20th century for his sister-in-law. This story is also an attempt to convince himself once and for all that he really is not culpable for her suicide, that he had behaved honorably. Ray's translation maintains this aspect of the short story perfectly. In both texts, the Amal character experiences an awakening, a realization that cultural norms had somehow, in some way, been violated. Once that realization occurs, the Amal character quickly disengages from Charu and Bhupati's household altogether. Moreover, he does his best to be supportive of his elder cousin-brother whom he feels he somehow has, inadvertently, deceived. This fictionalized character would appear to be saying in both Tagore's original and Ray's translation, "Look, I'm not to blame. What else could I do?"

Amal and Charu, in a scene from Charulata Though the Amal character makes a noble retreat, disengaging from Charu, Tagore in real life returned again and again emotionally, through his writings, even through his paintings, according to Nandalal Bose,[19] to what must have been a most wonderful and exciting and loving Kadambari Devi, whom he in return loved dearly. I shall conclude by reading yet another piece by him about her, again in his own translation:

She went away when the night was about to wane.

My mind tried to console me by saying, "All is vanity."

I felt angry and said, "That unopened letter with her name on it, and this palm-leaf fan bordered with red silk by her own hands, are they not real?"

The day passed, and my friend came and said to me, "Whatever is good is true, and can never perish."

"How do you know?" I asked impatiently; "was not this body good which is now lost to the world?"

As a fretful child hurting its own mother, I tried to wreck all the shelters that ever I had, in and about me, and cried, "This world is treacherous."

Suddenly I felt a voice saying -- "Ungrateful!"

I looked out of the window, and a reproach seemed to come from the star- sprinkled night, -- "You pour out into the void of my absence your faith in the truth that I came!"[20]

Alas, where will you go!

If you would go, then go, go, wipe your tears and go,

Leave your sadness here and go.

May the rest you'd sought be found there --

Sleep in comfort.

If you would go, then go.

Notes:

1 Probhat Kumar Mukherji, Life of Tagore, trans. by Sisirkumar Ghosh (Thompson, Connecticut: InterCulture Associates, 1975), p. 35.

2 Ibid., p. 45.

3 Ibid.

4 Rabindranath Tagore, Rabindra-racanabali, vol. 17 (Calcutta: Viswabharati, 1939, 1966), p. 484 (letter original published in Kavita magazine, Kartik, 1348)

5 Ibid., p. 423.

6 Rabindranath Tagore, Rabindra-racanabali, vol. 2 (Calcutta: Viswabharati, 1939, 1966), p. 46 (from Kadi o komal).

7 First published in the volume called The Fugitive and Other Poems, brought out by Macmillan, and subsequently included in A Tagore Reader, ed. Amiya Chakravarty (Boston: Beacon, 1966), p. 332.

8 Rabindranath Tagore, Rabindra-racanabali, vol. 26 (Calcutta: Viswabharati, 1948, 1959), p. 106-7.)

9 A Tagore Reader, p. 331.

10 Seton, Portrait, [Bloomington, IN and London: Indiana University Press, 1971] p. 180.

11 Ibid.

12 Robinson, Inner Eye [London: Andre Deutsch, 1989; Calcutta, Allahabad, Bombay, New Delhi: Rupa, 1990], p. 159.

13 Ibid.

14 Rabindranath Tagore, The Broken Nest (nashtanir), tr. Mary M. Lago and Supriya Sen, intro. by Mary M. Lago (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1971), p. 59.

15 Ibid., p. 63.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid., p. 64.

18 Quoted in Robinson, Inner Eye, p. 169.

19 Robinson, Inner Eye, Pg. 159.

20 A Tagore Reader, p. 331.

Illustrations: Computer-art by Nilanjana Basu, cut-out by Supurna Sinha.Published July 15, 2001

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us