-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Rabindranath Tagore | Essay

Share -

A People's Poet or a Literary Deity : Indrani Chakraborty

"His prose introduces us to life, his poetry teaches us what to do with it". Way back in the 60s writer Buddhadeva Bose had summed up the overwhelming presence of Rabindranath in our lives, with this eulogistic statement. But that was 1962. And this is 2001 - a crucial year for the Tagore enthusiasts, the year when the Vishwa Bharati copyright on the works of the poet expires. Like the economic liberalization, this literary liberalization will also perhaps mark a turning point in our cultural history.

Come the month May and the Bengalis in Calcutta and round the globe plunge headlong into the annual jamboree called Kabipranam - the observance of Tagore's birth anniversary. In fact, this is the time of the year when we are stricken by the Tagore-bug, which manifests itself in innumerable Rabindrasangeet concerts, recitals, staging of dance dramas, literary seminars and the release of a plethora of Rabindrasangeet albums. This unique Tagoremania attains a feverish pitch on ponchishe boishakh (which usually coincides with the 8th of May). This year is going to be no exception. After all, for any culture-conscious Bengali household, Kabiguru is the fountainhead of all that is aesthetically beautiful and intellectually supreme.

But doesn't all this brouhaha lead you to wonder - how much of Tagore, the Bard of Bengal, does the average educated Bengali really know? Is there a sincere interest in and appreciation of the poet's works or is this just a ritualistic practice of the middle-class with intellectual pretensions?

Probe a little into the Bengali psyche and don't be surprised if you find that for most, the Tagorean repertoire is limited to some 20 popular songs, 10 poems, 5 short stories and at best 4 novels (particularly the ones translated into films). It goes without saying that this is just a miniscule fraction of the poet's apparently inexhaustible oeuvre.

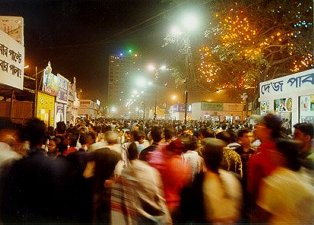

A scene from the Calcutta Book Fair, 2001.

A scene from the Calcutta Book Fair, 2001.An informal survey at this year's book fair served as an eye-opener. On a day when the fairground seemed to be bursting at its seams, I made an effort to quiz some of the visitors on their knowledge of the poet's works. For most, familiarity with Tagore's writings was restricted to the following: Puratan Bhritya, Birpurush, Sonar Tari (among poems), Chandalika, Shyama, Chitrangada (of the dance dramas). A sizeable portion of the crowd could also recall Kabuliwala, and Ghare Baire- among his prose works, primarily because they were familiar with the cinematic version. Therefore, it did not come as a surprise when 30 year-old Sandeep Guha (who works in a reputed foreign bank) cited Charulata as one of his favourite Tagore stories! He was a trifle surprised when reminded that Ray's masterpiece is actually based on the novella Nashtaneer. (In my contention, I have deliberately excluded students for whom many of Tagore's writings are a must read.)

Do the scholars and intellectuals exaggerate when they say that Tagore single-handedly moulded and refined our cultural consciousness? Our parents would recall a time when it was almost customary to present a newly married couple with a volume of Sanchayita, for it signified good taste and cultural awareness. Even today, bookshelves in many households boast of a complete set of the Rachanabali.But signs of leafing through the pages in most cases are far too few.

On one hand the characteristic hujug (I cannot think of a better expression) which marks the Rabindrajayanti celebrations of the ignorant many and on the other, the genuine Rabindrapremi, the knowledgeable few - where does the poet stand in between? Is he, after all, a people's poet or is he just the sage-like awesome creative genius for us to admire from a distance?

To seek an answer, I spoke to some of the noted writers of our time. Sanjib Chattopadhyay, for instance, went on to quote from Ramakrishna, "For a dip in the Ganges, one need not travel to the Gomukh - a plunge in the waters at Baranagar would do just as well.." he said in an emotionally charged voice. "Likewise, for that unique aesthetic experience called Rabindranath, one need not peruse 15 volumes of his works. Dabble in just a few of his poems, short stories, hum a few strains from his songs - it will certainly leave a mark on your sensibilities," he went on to explain. Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay agrees that in spite of the ignorance of the general readers, Rabindranath does have an all-embracing influence on our lives. Sunil Gangopadhyay has a different opinion, he asserts that Rabindranath is (or was) never a people's poet in the sense Kazi Nazrul is (or was). He agrees that our generation knows Tagore most intensely through his songs, which are readily accessible to all and sundry. "I think, Rabindrasangeet should also be sung in a manner befitting our age and times."

Debashis Roychowdhury, a Rabindrasangeet exponent, is involved in promoting Tagore culture among today's youth. He feels that the sharp decline in reading habit, inroad of consumerism, the boom in electronic media are some of the factors responsible for the apathy of the common readers not only towards Tagore but towards any other writer of some significance. He says, "I use Tagore as a tool to counter this cultural degradation. But Tagore's appeal is classic -- it would be fallacy to regard him as a pivotal point of our popular culture."

Let me draw one final quote from Buddhadeva Bose's Tagore: Portrait of A Poet : "He refined our manners and our language of everyday speech, he taught us to love and honour our mother tongue, he even metamorphosed our handwriting. Would it now surprise you if I say that modern Bengali culture -- if such a thing exists, and I believe it does -- is based on Tagore?"

Do we still share Bose's conviction? Today's idolator and the iconoclast - both will perhaps agree that the culture he is referring to is the domain of the intellectual elite. For the rest -- Gurudev will remain relegated to the position of the bearded-icon looking down at us in all his haloed glory.

Illustration by Nilanjana Basu

Published July 15, 2001 - এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us