-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Rabindranath Tagore | Essay

Share -

On the Trail of Rabindranath Tagore and Victoria Ocampo : Ketaki Kushari Dyson

Recently I happened to read in Parabaas Alfonso Chacon R.’s article ‘The Forgotten Stone: On Rabindranath Tagore and Latin America’ (2000), and from there by means of a cross-reference I went to Rajat Chanda’s article, ‘Tagore in South America: Some Perspectives’ (1991), also available on the Internet. There are actually two interlinked stories here. Tagore’s own influence on Latin America is one story. That story will be best pieced together by a Latin American scholar who can survey the entire field. I was pleased to learn from Alfonso’s article that Tagore continues to be a subject of study in many Latin American universities including Costa Rica and was interested in his analysis of why Tagore exerted the influence he did in Latin America: as a non-European model available to Latin American intellectuals emerging from European cultural domination. Further work along such lines would be a welcome contribution to the field.

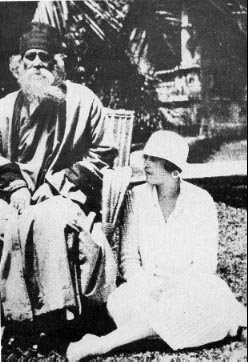

Fig 1: Tagore and Ocampo in the grounds of Villa Ocampo, the country house of Victoria’s parents. Victoria is sitting on the grass. The other story relates to Latin America’s impact on Tagore himself. Argentina is the only Latin American country where Tagore spent some time. He had planned a more extensive tour, taking in Peru and Mexico, but other events intervened, and his Latin American adventure remained more or less centred in a personal encounter with the Argentine woman of letters, Victoria Ocampo, which bore fruit in his creative work as indeed in the life-work of Ocampo herself.

I can truthfully claim to be the person who has conducted the most extensive investigations into Tagore’s Argentine adventure and his interaction with Victoria Ocampo, and I also happen to be the official editor of their correspondence. I must confess that I was therefore disappointed to see that neither author of the two aforementioned articles was familiar with the latest researches in this area and that as a result errors had crept into their presentations. Errors should not be perpetuated in the electronic media when reliable information is available in published books and papers. I got in touch with the editor of Parabaas, and he kindly invited me to contribute an article in the special issue on Rabindranath Tagore. I shall present an overview of my own involvement in Tagore-Ocampo research and pull together some of the main threads of their story. I shall also offer some further thoughts in response to queries the editor of Parabaas has posed. I should mention right at the outset that to avoid the problems that can come from trying to include a variety of diacritical marks on a web page, I am reluctantly having to omit the Spanish and French accents from my orthography.

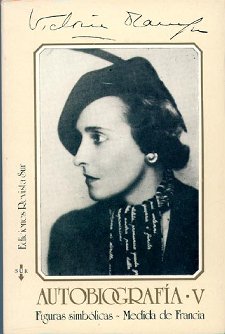

Fig.2: Front cover of Victoria Ocampo’s Tagore en las barrancas de San Isidro, second edition (1983).

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

Fig.3: Front cover of Sankha Ghosh's Ocampo'r Rabindranath fourth edition (1998).

We Bengalis have known for some time that Victoria Ocampo became a distant Muse to our great poet in the last seventeen years of his life: his Argentine hostess of 1924, the woman to whom he gave the name Vijaya and to whom he dedicated his book of poems, Purabi, in 1925. Ocampo’s long essay ‘Tagore on the Banks of the River Plate’ has been available since 1961 in the Tagore Centenary Volume published by Sahitya Akademi, India’s National Academy of Letters at New Delhi. The same year, 1961, saw the publication in Buenos Aires of her book Tagore en las barrancas de San Isidro (‘Tagore in the Ravines of San Isidro’). A Bengali version of this book by the poet and academic Sankha Ghosh, embedded in his book Ocampor Rabindranath (‘Ocampo’s Rabindranath’), published by Dey’s of Calcutta, has been available since 1973. This version was prepared not directly from the Spanish, but from an intermediate English text prepared by someone else. There are, inevitably, a few problems, but updated and revised from time to time, the work has provided Bengali readers with the essential substance of the original book, with many useful notes. Thus an outline of the story of the poet and his Vijaya and the fact that she was a distinguished woman have been known to us for a long time in a rough sort of way, but her own testimonies about her encounter with Tagore could never give us a fair idea of her true stature in the context of Latin America and the world. A writer, an editor, a publisher, a cultural entrepreneur, and a feminist, she was one of the remarkable women of the twentieth century. Something of this was first revealed to us on the publication, shortly after her death, of her first full-length English-language biography by an American academic named Doris Meyer (Victoria Ocampo: Against the Wind and the Tide, George Braziller, New York, 1979). This book made us realize that

Fig. 4 Fig.5 Fig.6

Fig.4: Front cover of Victoria Ocampo’s book La laguna de los nenufares, 1982 edition. It was first published in 1926.

Fig.5: Front cover of Sur, January-June 1980, an issue paying tribute to the memory of Victoria Ocampo, who had just died in 1979.

Fig.6: Front cover of Ocampo’s Testimonios, second volume, edition of 1984. Although the cover here says 1937-1940, this volume does contain one or two pieces from 1941, including Ocampo’s obituary essay on Tagore, written in August 1941.

Victoria Ocampo deserved to be known and studied in her own right and not just as Tagore’s Muse. It spurred me on to discover her for myself. I had just begun to teach myself a little Spanish, a language to which I had been attracted for some time, and now I struggled with it with renewed determination in order to unlock the world of Victoria Ocampo. I realized then that of all the gifted and attractive women with whom Tagore had come into direct contact in his long life - and there had been quite a few of them - Ocampo had possibly been the most distinguished. When her own long life and its work are considered in their entirety, she is the closest to him in stature. It is only when the two vitae are placed side by side that we realize how unique a meeting theirs was.I reviewed Doris Meyer’s biography of Ocampo for the Bengali quarterly Jijnasa and began a serious effort to teach myself to read Spanish so that I could read Ocampo’s work in the original. I was very lucky to be able to read in Oxford University’s Taylorian Library, which has a good collection of Latin American books. I discovered that this library had Ocampo’s essays, Testimonios, collected in several volumes, as well as the back issues of Sur, the magazine she had founded. Soon I came across Ocampo’s obituary essay on Tagore, written immediately after his death in 1941. Bengali scholars were unaware of it, so I translated it into Bengali and published it in Jijnasa too. I then discovered an important cache of letters in an English archival collection (Elmhirst Records Office, Dartington Hall) which revealed to me that there was much more to the Tagore-Ocampo story than we had realized: the role played in it by the Englishman Leonard Elmhirst, Tagore’s honorary secretary and travelling companion, who was with Tagore throughout the Argentine sojourn. The friendship was actually triangular from the start. My first archival findings on the subject and fragments of translation from Ocampo’s essays were incorporated by me into the body of a book I wrote in Bengali in 1981-82 in a mixed genre, pioneering the mixture of fiction and non-fiction within the same work.

In this book, entitled Rabindranath

o Victoria Ocampor Sandhane (‘In search of Rabindranath

Tagore and Victoria Ocampo’), I interwove fiction with

research and translation work, giving my own work to the heroine

of my novel. The book went to the press at the end of 1982,

though due to circumstances at the press’s end, beyond my

control, it did not see the light of day until 1985. Originally

published by Navana, it is now available in an edition from

Dey’s.

In this book, entitled Rabindranath

o Victoria Ocampor Sandhane (‘In search of Rabindranath

Tagore and Victoria Ocampo’), I interwove fiction with

research and translation work, giving my own work to the heroine

of my novel. The book went to the press at the end of 1982,

though due to circumstances at the press’s end, beyond my

control, it did not see the light of day until 1985. Originally

published by Navana, it is now available in an edition from

Dey’s.Meanwhile, Rabindra Bhavana, which houses the Tagore archives in Visvabharati, Santiniketan, initiated a new project. I was asked to edit and annotate the Tagore-Ocampo correspondence with a suitable introduction. As the letters exchanged by Tagore and Ocampo are in English, their only common language, this new book would have to be presented in English. In 1983 I spent two months in Santiniketan, examining the documents kept there. Ocampo’s original letters to Tagore are held there. In 1984, I visited Paris at the invitation of the Permanent Argentine Delegation to UNESCO and talked to a few people in Paris who had known Victoria Ocampo well. To complete my researches I needed to get to Buenos Aires where the originals of Tagore’s letters to Ocampo were. This was a great struggle, but finally in 1985 I got there with the assistance of India’s ICCR. Hospitality at the Argentine end had been promised, but in the event efforts to organize this proved unsuccessful. In political terms those were difficult days. In Argentina the rule of the junta had been overthrown and democracy had just been restored; Alfonsin was in power; but the time was still close to the Falklands dispute. I had travelled on a UK passport, and there was still no diplomatic relationship between Argentina and the UK. In the end I simply stayed for two months as the private guest of the Indian charge d’affaires in Buenos Aires, grateful that I could at last proceed with a crucial phase of my researches.

Fig. 8 Fig. 9

Fig.8: An item about Tagore’s stay in Argentina in Radio Cultura, 10-16 November 1924. Inset is the Spanish version of a Tagore song. Fig.9: A news item in La Nacion of 7 November 1924 announcing Tagore’s arrival in Buenos Aires and showing Tagore with Ricardo Rojas, an academic who headed the reception committee which had been formed to welcome him.

In Buenos Aires I examined a large quantity of archival papers, back issues of newspapers, and press cuttings, and interviewed many people: friends and colleagues who had known Ocampo intimately, and family members including Silvina Ocampo, Victoria’s youngest and sole surviving sister at that time, and her husband Adolfo Bioy Casares, both of them distinguished writers in their own right and both now dead. Working in the archives presented severe problems. Due to financial constraints they were open only for restricted hours. There were no xeroxing facilities. All notes had to be taken manually. But at least the original documents I desperately needed were there at that time. Now, I gather, they have been transferred to a North American academic library.After returning from Argentina I started to give shape to the new book. By that time I had gathered a massive amount of data from my work in three major locations in three continents, from talking to people in India, Britain, France, the United States, and Argentina, and from covering a bibliography in four languages, Bengali, English, French, and Spanish. Among other things I read substantial sections of the Testimonios volumes and also all the volumes of Ocampo’s posthumously published autobiography,

Autobiografia, as they came out

one by one; Alba Omil’s portrait of Ocampo (Frente y

perfil de Victoria Ocampo, Sur, Buenos Aires, 1980); John

King’s Oxford doctoral dissertation, Sur and Argentine

Culture 1931-1970, submitted in 1982; that grand, invaluable

collection of essays in honour of Victoria Ocampo, entitled Testimonios

sobre Victoria Ocampo (Buenos Aires, 1962); and the important

essay, ‘Los manuscritos de Tagore’ (1967) by Octavio

Paz, whom I actually had the honour of meeting in 1985 in Buenos

Aires. The letters I was supposed to be editing were only a

handful, but they would not be adequately illuminated unless the

introduction I had been asked to write was much bigger and more

detailed than what we had originally visualized at the inception

of the project. The Argentine setting of the story needed to be

made clearer to Indian readers, who would have only a hazy notion

of the socio-cultural backdrop against which the meeting between

Ocampo, Tagore, and Elmhirst took place. In the end a sizeable

book grew out of the venture. What was going to be the

introduction developed into a substantial study divided into

twenty chapters. These chapters form the first part of the new

book, the letters and cables exchanged by Tagore and Ocampo being

the second part. I have included an epilogue containing a few

letters and cables exchanged by Ocampo and the poet’s son,

Rathindranath Tagore, after the poet’s death. An Appendix

lists the contributions made by Tagore to the newspaper La

Nacion of Buenos Aires. There are also 33 relevant plates.

Entitled In Your Blossoming Flower-Garden: Rabindranath Tagore

and Victoria Ocampo, the book was published in 1988 by

Delhi’s Sahitya Akademi and is currently available in its

second printing. It was well received in India and had a very

positive review in La Nacion of Buenos Aires in 1990, the

year of Ocampo’s birth centenary, which is why I am

surprised to find that it was not consulted by those who have

written in the electronic media. Sadly, this indicates the

genuine lack of publicity and circulation which Indian

publications face in the New World.

Autobiografia, as they came out

one by one; Alba Omil’s portrait of Ocampo (Frente y

perfil de Victoria Ocampo, Sur, Buenos Aires, 1980); John

King’s Oxford doctoral dissertation, Sur and Argentine

Culture 1931-1970, submitted in 1982; that grand, invaluable

collection of essays in honour of Victoria Ocampo, entitled Testimonios

sobre Victoria Ocampo (Buenos Aires, 1962); and the important

essay, ‘Los manuscritos de Tagore’ (1967) by Octavio

Paz, whom I actually had the honour of meeting in 1985 in Buenos

Aires. The letters I was supposed to be editing were only a

handful, but they would not be adequately illuminated unless the

introduction I had been asked to write was much bigger and more

detailed than what we had originally visualized at the inception

of the project. The Argentine setting of the story needed to be

made clearer to Indian readers, who would have only a hazy notion

of the socio-cultural backdrop against which the meeting between

Ocampo, Tagore, and Elmhirst took place. In the end a sizeable

book grew out of the venture. What was going to be the

introduction developed into a substantial study divided into

twenty chapters. These chapters form the first part of the new

book, the letters and cables exchanged by Tagore and Ocampo being

the second part. I have included an epilogue containing a few

letters and cables exchanged by Ocampo and the poet’s son,

Rathindranath Tagore, after the poet’s death. An Appendix

lists the contributions made by Tagore to the newspaper La

Nacion of Buenos Aires. There are also 33 relevant plates.

Entitled In Your Blossoming Flower-Garden: Rabindranath Tagore

and Victoria Ocampo, the book was published in 1988 by

Delhi’s Sahitya Akademi and is currently available in its

second printing. It was well received in India and had a very

positive review in La Nacion of Buenos Aires in 1990, the

year of Ocampo’s birth centenary, which is why I am

surprised to find that it was not consulted by those who have

written in the electronic media. Sadly, this indicates the

genuine lack of publicity and circulation which Indian

publications face in the New World.It was the award of the Nobel Prize for literature to Tagore that made his encounter with Victoria Ocampo possible. The Nobel Prize made Tagore internationally famous. English versions of his works were re-translated into many other languages. He reached, as the Nacion of Buenos Aires rightly claimed, a world-wide audience. He received invitations from many countries, travelled and lectured widely, widened his artistic and political experiences, acquired foreign friends, and met many other distinguished personalities of his time. These experiences enriched the elements of cosmopolitan humanism in his thinking, invested his life with a new international dimension, and thereby accelerated his self-modernization in many areas of being and doing.

Victoria Ocampo was an ardent admirer of Tagore’s works, which she could read in English, French, and Spanish versions. While the intensity with which she greeted his works was a very personal gesture of hers, deriving its vivid colours from her private life, it was, at the same time, a part of the widespread enthusiasm for Tagore that prevailed in Latin America at that time, a phenomenon to which Octavio Paz has testified. In Mexico Tagore was recognized as a universal classic, and in Chile poets like the early Gabriela Mistral and the early Pablo Neruda were influenced by Tagore’s style. On one level, the story of Ocampo’s interaction with Tagore belongs to that larger story of the reaction of the Spanish-speaking world to Tagore. Paradoxically, Ocampo was not too keen on the Spanish versions of Tagore prepared jointly by Zenobia Camprubi and her husband, the poet Juan Ramon Jimenez, which were so immensely popular among Spanish-speakers. The Jimenez couple made a remarkable contribution to the Tagore vogue in the Spanish-speaking world. I shall return to this subject later in this article. Ocampo, however, always maintained that she preferred the French version of the Gitanjali by Andre Gide to the Spanish version. But Ocampo was Hispanic in her passion, and in so far as the Hispanic and Latin American enthusiasm for Tagore was due to an overlap of artistic and mystical modalities between the world of Spanish-speakers and the Indian world, Ocampo’s response to Tagore was in consonance with the general pattern. In keeping with her own character, she brought a vibrant and insistent personal element into the interaction. However, we have to remember that Tagore did receive ardent homage from a number of other foreign women whom he met or with whom he corresponded, including the already mentioned Zenobia Camprubi, the Paris-born Andree Karpeles, the German Helene Meyer-Franck, and the Hungarian Elizabeth Brunner. Not only speakers of Spanish, but other women too responded generously to the power of his books or the magnetism of his personality.

Like Tagore, Victoria Ocampo was born into a wealthy and aristocratic milieu, into a class which had been actively involved in the making of the history of the region. Through her father’s side as well as through her mother’s side, she inherited a family background the ramifications of which are intertwined with the story of the development of Argentina from a colony of Spain into a separate South American nation. At the time of her birth the Argentine nation was still in the making. Buenos Aires, her birthplace, soon to become a grand metropolis, still deserved, in 1890, the year of her birth, the nickname of ‘Gran Aldea’ or ‘Big Village’ which had been affectionately bestowed on it. The families of Spanish origin which had fought for the emancipation of Argentina from Spanish imperial rule were firmly in control of affairs. Ocampo was born into what might be called a clan, a tightly knit group of families which were mutually related by ties of blood and marriage, friendships and enmities, quarrels and reconciliations, and by their common faith in the new Argentine nation that was emerging. As a child, she heard of the events of the past 80 years as family affairs. Unlike the class into which Tagore was born, which, although representing a strong native elite, was nevertheless in a state of political subordination to British power, the class into which Ocampo was born was the ruling class of the region, an oligarchy which held both economic and political power. There was a British connection here as well. Argentina’s phenomenal economic expansion in the latter part of the nineteenth century, spilling into the twentieth, owed a great deal to her special link with Britain. There was a vigorous trade between the two countries and there was a lot of British capital invested in Argentina. It was this connection that gave English as an additional language to the children of the Argentine oligarchy, which enabled Victoria Ocampo to communicate with Tagore in some depth. Argentina happened to be the most European and Europe-oriented of the South American nations.

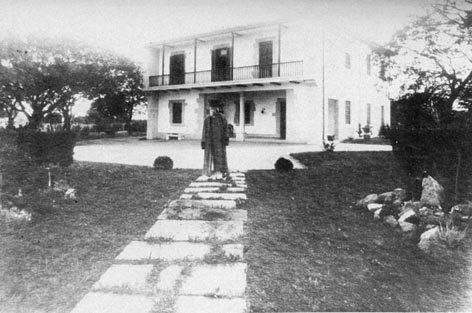

Fig 11: The large salon or reception room of Miralrio, where Tagore sometimes received visitors. It is now used mainly as a dining-room, and this is where I had lunch when I visited Miralrio on 19 May 1985. Victoria’s father, who was about the same age as Tagore, was a civil engineer who built a fortune by building roads and bridges in the interior of Argentina, especially bridges for the British-financed railways. Victoria was the eldest of six siblings, all sisters. They were educated at home under the supervision of French and English governesses, as was the custom in their class. Victoria became fluent in French and English at an early age and read widely in the classics of both literatures. She emerged from her education with French as her first cultural language, English as her second cultural language, and Spanish as the language of rough, daily use. This caused a problem when she started writing. In the beginning she wrote only in French. Then, in her forties, she taught herself to write in Spanish, slowly and painstakingly, first making a draft in French, then translating herself into Spanish. She eventually became the mistress of an admirable Spanish prose style. She could also read Italian, her first book being a personal commentary on Dante’s Divina Commedia.

European travels were regarded as an essential part of education for the children of her social class. Her first trip to Europe was at the age of six. The second one was a stay of about two years from her eighteenth to her twentieth year. During this trip she attended some lectures, chaperoned, in Paris, but whether at home or abroad, there was no question of her going to university on a regular basis. One interesting point of similarity between Tagore and Ocampo is that neither attained any formal academic qualifications - one dropped out of academies and the other was kept out of them - but nonetheless both created major cultural institutions in their own countries, Tagore with Santiniketan, Sriniketan, and Visvabharati, and Ocampo with her magazine and publishing-house.

As a girl, Victoria was brought up within a restrictive Hispanic moral code. She could not go out into the street without a chaperon. She was not allowed to read certain books. She wanted to become an actress; there was no question of a girl from her class becoming an actress; it was not respectable. It was a frustrated actress who turned to writing as an outlet. Basically, there was no concept, in the milieu in which she was raised, of a career for a woman, except, that is, as a wife, mother, and homemaker. It was an upper-class society dominated by the two mutually supporting institutions of the Catholic Church and the extended patriarchal family. Victoria too began with wifehood. The marriage to Monaco Estrada was preceded by the usual formal courtship approved of by her society and class, but it was a disaster almost from the beginning. It did not work out at all. Just a few months after her wedding, while on honeymoon in Europe, Victoria met and fell in love with Julian Martinez, a cousin of her husband’s. After returning to Buenos Aires, she commenced a clandestine affair with him which was to last for many years. No divorce was available in Catholic Argentina. Afraid of hurting her parents, she could not live with Martinez openly. For some eight years she lived under the same roof as her husband, without sharing his bedroom or talking to him except on social occasions. She hid her love-affair from virtually everybody, meeting her lover secretly. In 1922, she stopped living in the same house as her husband and moved into a flat of her own. She obtained a legal separation from her husband - not divorce, which was not available - but did not make her affair public. Everybody knew that she had a broken marriage, but hardly anybody knew that she also had a lover. This was the situation when she first met Tagore, when she was 34 and he was 63. Victoria never remarried, even after the death of her estranged husband. She had several very important relationships with men, but she refused to accept the bondage that marriage meant in Latin American society.

Victoria first read the Gitanjali, in Andre Gide’s French re-translation, in 1914, an event which she has always described as her first encounter with Tagore. An intensely emotional experience, the discovery of the Gitanjali was subsequently elevated in her memory into a profoundly spiritual experience. It was a time of crisis in her life: her marriage was already a failure and she was hopelessly in love with Martinez. She wept when she read the Gitanjali: it was like an act of recognition, a release, a liberation. She recognized her own intense emotions in the mystical yearnings of the poems and at the same time found a deep spiritual comfort in it. She began to read Tagore in translation, whatever was available, in English, French, or Spanish, with great hunger and intelligence.

Early in 1924 Victoria discovered the thoughts and ideals of Mahatma Gandhi through Romain Rolland’s book on him, which was creating a stir. Later that year Tagore arrived at Buenos Aires, ill with influenza, on his way to Peru. He had been invited to attend the hundredth anniversary of the battle of Ayacucho, celebrating Peru’s independence from Spain. He was accompanied by his honorary secretary, Leonard Elmhirst, the future founder (along with his North American wife, Dorothy Whitney Straight) of Dartington Hall. Educated initially at Cambridge, Elmhirst had trained in agriculture at Cornell, from where he had gone to assist Tagore in the setting up of a rural reconstruction centre based in the village of Surul, adjacent to Santiniketan: the beginning of Sriniketan. Tagore was looking forward to a fruitful lecture-tour in Latin America: he was interested in observing the relics of the Incas, while valuable funds had been promised for Visvabharati by Peru and Mexico. The state of his mind at the time of his arrival in Buenos Aires is indicated very clearly in an interview he gave to a journalist of the Nacion on board the Andes between Montevideo and Buenos Aires. In addition to giving it coverage in my English book, I have also translated this very interesting interview in its entirety into Bengali for a collection of Tagore-related essays entitled Raater Taaraa Diner Rabi, edited by Ujjvalkumar Majumdar (Ananda Publishers, 1988).

Tagore intended to spend only a few days in Buenos Aires, in which time he hoped to meet members of the Argentine intelligentsia and also to get to know the old Argentina portrayed in the books of his favourite author W. H. Hudson. He didn’t know that this old Argentina didn’t really exist any more, certainly not around Buenos Aires, which had become a thriving, bustling, modern, cosmopolitan city. He had caught a nasty influenza on board, had become exhausted, and the doctors at Buenos Aires would not let him proceed to Peru, as the Andean train journey was considered to be dangerous for his heart. He was ordered complete rest, preferably in the countryside. Victoria Ocampo, accompanied by her friend Adelia Acevedo, called on him at the Plaza Hotel, and offered to host the poet and his secretary in a villa in a suburb of Buenos Aires. The offer was accepted. A relative named Ricardo de Lafuente Machain, the husband of a first cousin of Victoria’s through her mother’s side, let Ocampo use a villa overlooking the Rio de la Plata, situated in the suburban district of San Isidro.

Fig. 12 Fig. 13 Fig 12: Miralrio in the 1920s, with the tipa tree under which Tagore sometimes sat to talk to visitors. Fig 13: Front cover of the Sunday supplement of the Buenos Aires paper La Nacion, 1 April 1990, showing the villa Miralrio as it is today and calling it the ‘escenario de una historia de amor,’ the setting of a love-story. The supplement was in anticipation of Victoria Ocampo’s birth centenary (she had been born on 7 April 1990) and this picture went with a cover story largely based on my book In Your Blossoming Flower-Garden.

The beauty of this villa, Miralrio, and its location has to be seen to be believed. The day I spent there with the wife and daughter of the present owner still stands out in my memory like a day of pilgrimage in my life. In 1924 this exquisite villa was newly built. Ramiro R. de Lafuente, the present owner and son of Ricardo de Lafuente, has reminisced to me that the house was finished almost on the date of his birth, and he was about three years old when Tagore was there. Tagore’s stay there is like a family legend, and a picture of his used to hang in the house for years until it was removed when the house was rented. In the twenties the house had a cactus garden at the back, and was very close to the river. Now the river has moved away a little, though it still looks magnificent when viewed from the famous balcony of the villa. Ocampo, who had studied Tagore as carefully as she could through the medium of the translations then available, and was aware of Tagore’s deep love of rivers, realized that the view of the river from the balcony of Miralrio was the only gift worthy of him that she could offer. Originally Tagore’s stay in Miralrio was going to be only for a week, but eventually it became a stay of nearly two months. Tagore never went to Peru. Victoria Ocampo sold a piece of jewellery (her famous diamond tiara) to keep Tagore and Elmhirst in the villa for the two months. She also obtained free passages for them back to Europe aboard the Italian liner Giulio Cesare, on which four Purabi poems were written. Victoria did not herself sleep at Miralrio; she slept at her parents’ country house, Villa Ocampo, just a few blocks away, but went to see Tagore and have meals with him nearly every day. Tagore’s mundane needs were looked after by Victoria’s personal servants, including her nurse or nanny, the redoubtable Fani, who has been subsequently immortalized by her mistress in various parts of her writings, especially in one essay dedicated to her memory after her death. Tagore and Fani could apparently carry on a conversation even though they didn’t really have a language in common. Fani established a rapport with Tagore and kept an eye on Elmhirst. She was used to this kind of role, having guarded her mistress through the years of her marital breakdown. Tagore and Elmhirst had adjacent first floor bedrooms, both opening into the balcony which faced the river. The two months in San Isidro - November and December, 1924, springtime merging into summer in the southern hemisphere - were a complicated time. They were idyllic in some respects, but they were also tempestuous in other respects. Emotional storms, stemming basically from Ocampo’s desire to keep Tagore in Argentina for as long as possible and to establish a proper communication with him at an intellectual level, while Tagore wanted to keep his engagements in Peru, are recorded in notes exchanged between the three, in some notes exchanged between Tagore and Ocampo, but especially in a number of notes exchanged between Elmhirst and Ocampo, and also in a partial journal that Elmhirst kept during those days. I have explored this documentary evidence very thoroughly in my two books, but one thing which is not at all clear from the evidence available is what Julian Martinez was doing during those weeks and if Ocampo continued to see him secretly while Tagore was installed in Miralrio. Nothing is said about this in her autobiography either. It doesn’t seem that Tagore and Elmhirst were introduced to him.

A stream of visitors came to pay their respects to Tagore while he was at Miralrio. He had strict medical orders to take rest, but he wouldn’t listen. Both Ocampo and Elmhirst had to struggle to make him comply. Tagore felt he had to talk to everybody who came to see him. The tipa tree under which he sometimes sat to talk to them still stands in the garden.

Fig 14: Rabindranath Tagore and Leonard Elmhirst with Miralrio just behind them. The friendship with Tagore was initiated by Victoria Ocampo out of the very genuine admiration she felt for him, out of an intense spiritual urgency and personal searching. The friendship was triangular from the beginning, encompassing Tagore, Ocampo, and Elmhirst. It was really Elmhirst who persuaded Tagore to accept the invitation to stay in Miralrio and it was he who witnessed the encounter between the poet and her hostess from that base. He helped the two to get to know each other and at the same time played a role much more complicated than that of a simple mediator. Ocampo had this overwhelming desire to establish rapport with Tagore, but was paralyzed by shyness in the proximity of that venerable poet, who was both far and near, friendly and distant, gentle and reserved. She leaned heavily on the mediation of Elmhirst, who was by no means immune to her charms himself, but she was at the same time jealous of his closeness to Tagore. There is evidence that Elmhirst, who was then engaged to Dorothy Straight after several years of a difficult and strenuous courtship, also felt considerable attraction toward Victoria. Tagore fretted at not being allowed to proceed on his Peruvian journey, was slightly jealous of the growing friendship between Ocampo and Elmhirst, and at the same time responded to Ocampo’s ardent devotion. He spent leisurely hours looking at the river from his balcony, and wrote poems. He indulged in the doodlings with MS erasures from which his visual art eventually emerged. The three, accompanied by Victoria’s friend Adelia Acevedo, spent a week at Chapadmalal, near Mar del Plata, where also a few poems were written.

Altogether, about a third of the Purabi poems have an Argentine connection. Though Tagore was diligent in minimizing explicit references to the actual locale, the poems record with seismographic accuracy the occurrence of an emotional upheaval in the poet. When Tagore and Ocampo parted in January 1925, they had plans to meet again soon in an Italian villa, but this plan never materialized. In 1925 Tagore was not well enough to return to Europe, and in 1926, when Tagore made a triumphant tour of Europe, some of the time in the company of the young and vivacious Rani Mahalanobis, Ocampo did not succeed in coming to Europe to meet him. As is clear now, but was hidden from view then, she was geographically tied to Buenos Aires because of Julian Martinez, and the link was not so easy to sever. In addition she was also preoccupied with her growing friendship with the Swiss musician, Ernest Ansermet.

In the story of Tagore and Ocampo, the armchair she gave him occupies a special niche. This was a chair that Ocampo lent to Tagore during his stay in Argentina for his convalescence and which she insisted that he take back with him. It would not get through the door of the ship’s cabin. She had the captain of the ship get a workman to remove the door from its hinges so that the chair could go in. The process had to be repeated to get the chair out at the other end in Italy. This chair, which then accompanied Tagore from Italy to India, is preserved at the Rabindra Bhavana in Santiniketan. During his voyage out Tagore claimed that the chair had enabled him to understand at last a particular poem of Baudelaire’s (‘L’Invitation au Voyage’), which he had not appreciated before when Ocampo had tried to read it with him. Tagore had jocularly called Baudelaire a ‘furniture poet’. Ocampo in turn hoped that the chair would reveal to him at least some of the meaning of her devotion. There are strong erotic nuances in these jokes. Tagore wrote two poems on this chair in the months before his death in 1941.

Fig 15: Ocampo and Tagore: the last farewell, Paris, May 1930. Tagore and Ocampo met only once more, in 1930, in France. It seems that the meeting was not premeditated. Ocampo’s private life had gone through some significant upheavals which were unknown to Tagore. In the late twenties Ocampo had developed a great admiration for the works of the Prusso-German thinker, Count Hermann Keyserling. In 1928-29, after an interval of some 15 years since her last trip to Europe for her honeymoon, she came to Europe to meet Keyserling. It was a disastrous encounter. She could not respond to his advances, and trying to escape from an impossible situation, she established a relationship with a young French author, Pierre Drieu La Rochelle. Through him she made many new friends in Paris. It was partly to meet Drieu and partly to discuss her projected magazine with her French friends that she came to France in 1930. By this time Tagore had become a full-fledged visual artist: he had brought a large number of his pictures with him in the hope of organizing an exhibition in Paris. Victoria Ocampo was at first taken aback by this proposal, but by this time she had many contacts in Paris, and was able to organize his first ever proper art exhibition, in Paris, at very short notice. That was in May 1930. The exhibition was a success, was repeated in several other European cities, and was also taken to North America.

Tagore and Ocampo never met again. Ocampo became deeply involved with the foundation of her magazine, Sur, which she launched in 1931. Not only did she not manage to go to India and visit Tagore and his beloved Santiniketan, she never came to India at all, though she lived to be 88 and though India was the home of three of her major heroes: Tagore, Gandhi, and Nehru. In the beginning, it was Ocampo who suffered more because of the difficulties inherent in the situation between herself and Tagore, but in the long run, perhaps it was Tagore who suffered more. Tagore had responded to her devotion and had hoped that she would come and stay for a prolonged period near him in Santiniketan. The hopes slowly faded as Ocampo got more and more engrossed in her literary and editorial career in Argentina. Nevertheless, though they did not meet again, it is correct to say that each had a deep influence on the other’s psyche at a subterranean level. This influence surfaced in their work.

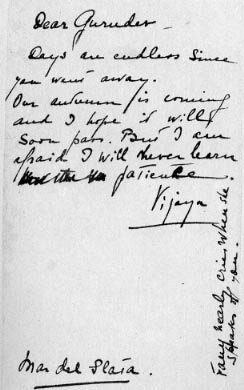

Fig 16: Victoria’s letter to Tagore from Mar del Plata, written on the back of a photograph of herself and posted on 25 February 1925. Tagore had been a widower since the age of 41 and nurtured a core of loneliness within his soul. The need for a feminine touch in his day-to-day life as well as his deeper artistic need to be inspired by a woman remained, to be partially filled, from time to time, by various women of the family and by other attractive women who clustered round him, magnetized by his personality and fame. In the period prior to his South American trip he had received companionship and inspiration from the young girl who later became that well-known arts patron of Calcutta: Lady Ranu Mookerjee. Ranu is known to have inspired the character of Nandini in Raktakarabi (Red Oleanders). Tagore was therefore very vulnerable in San Isidro when in the company of his youthful and ardent admirer. He interpreted Ocampo’s homage as love, partly responding, partly running away, overpowered by her gift, at the same time planning for a future meeting. In an unpublished part of Ocampo’s draft memoirs in French, there is a description of an incident which indicates that Tagore did feel an erotic attraction toward her; another incident recorded in the same source indicates that Elmhirst too felt this attraction. In her autobiography, written in her sixties and published after her death, Ocampo has stated that her love for Tagore was entirely spiritual. This was undoubtedly true of her love in the later years, but in my personal opinion this statement cannot represent the whole truth about her feelings, especially in the crucial years of 1924-25. It is certainly contradicted by the intensity of the letters she wrote to Tagore, which contain many traditional and passionate love-statements.

The immediate harvest of Tagore’s Argentine encounter is contained in some of the poems of Purabi and in the meditations on love in the latter part of Pashchimyatrir Diary. A curious feature of these meditations is that Tagore does not mention the adventure he has just had in Argentina. They are very defensive and all the more charged with irony because of the omission of the context. The shadow of the encounter must also be lurking in an oblique way behind an essay on the ideal of Indian marriage he wrote in the summer of 1925. The essay has two versions, not exactly parallel, one Bengali and one English. The English version was included in a collection of essays by various thinkers, edited by Keyserling and called The Book of Marriage: A New Interpretation by twenty-four leaders of contemporary thought, published from New York in 1926. This is the same Keyserling with whom Victoria Ocampo was to have a fairly disastrous encounter in 1929. Tagore’s essay was in fact written at the request of Keyserling himself. The projection in it of the Indian ideal of the man-woman relationship is ironical in the context of Tagore’s recent experiences and Victoria’s own broken marriage. Did Tagore know that Victoria had in fact sharply repudiated the traditional wifely and maternal roles of womanhood?

A curious feature of the Tagore-Ocampo story is Ocampo’s silence, for three crucial years, 1926, 1927, 1928, when she was sorting out her own life in Buenos Aires. During this period, she did not, it would seem, write to Tagore. It is very likely that there is a connection between this silence and Tagore’s conspicuous creative activity in the late twenties of this century. Right up to the beginning of 1926 Tagore was hoping to meet Victoria in Europe. She didn’t go to Europe. Tagore took consolation in the company of the charming Mrs Mahalanobis and plunged himself into a grand European tour. In 1927 he began Yogayog and visited South-East Asia. In 1928, he set off for England, hoping to give the Hibbert Lectures at Oxford, but had to come back from Ceylon because of ill health and to postpone plans of going to Europe. He might have been planning to ask Victoria to come to Europe. She, in any case, wasn’t writing. And he must have suffered in silence, because there was nobody near him with whom he could have shared his hopes and disappointments in this matter. So there was something like the blowing up of a long, slow fuse. In 1928 Tagore finished Yogayog, wrote the poetic novel Shesher Kabita, wrote most of the poems of Mahua, and began a great leap forward in drawing and painting. The love-poems of Mahua are likely to be linked to a memory which refused to fade away and to the tension of waiting to hear from Victoria for the third year running. In Shesher Kabita he may have given some of Ocampo’s endearing traits to Labanya and some of her superficial high society characteristics to Katie Mitter. The Shillong scenario created in that novel may owe something to the barrancas of San Isidro and the goings on at Miralrio and Villa Ocampo.

The memory of Victoria Ocampo is quite real, though subtle, in Tagore’s post-Mahua poetry and also in the songs he composed in the period subsequent to his Argentine experience. I have been made even more aware of it while translating his poetry. One can even trace the resurgence of hope after the reunion with her in France in 1930 and then the slow fading of that hope over the years as Ocampo failed to come to Santiniketan.

Victoria Ocampo prided herself on the fact that she encouraged Tagore in his manuscript doodlings from which his visual art eventually emerged. She also took considerable pride in having arranged his first art exhibition. The oval female face with brooding eyes that comes to haunt Tagore’s art especially after 1930 may well have a connection with her face. One of the themes of Tagore’s visual art which fascinated me greatly while looking at the Santiniketan collection is human figures in relation to items of shelter-giving furniture. I suspect that this theme may have some connection with the armchair which Ocampo gave him and the jokes about furniture which they exchanged. His increased openness to feminism in the thirties almost certainly owes something to the meeting with Ocampo. About this last point I have written at length in my Bengali book. Summing up, the relationship gave him, in a critical period of his life, the invisible energy, the shakti that he believed a woman’s love could give to a man’s struggle for self-fulfilment. An urge to rejuvenate himself and an anxiety to beat the arrogant young moderns in their own games assert themselves vigorously in his last years. While Ocampo never came to India, she never withdrew her love, and however much Tagore the man might have been disappointed, for Tagore the artist, his nature and long-inculcated self-discipline being what they were, that was enough to draw inspiration from.

As for Ocampo, Tagore’s influence is visible at a fundamental level in the gradual unfolding of her career. Her admiration of the Indian poet arose from a cosmopolitan consciousness accustomed to discovering values in foreign texts and prepared to seize its heritage from anywhere in the world if the opportunity presented itself. Her horizons had already been broadened by the study of different languages and literary traditions, so that she could perceive a great poet in Tagore through the intervening layers of translation. It is a great pity indeed that she could not read him in the original. But aware as she was of the shortcomings of the available translations, and of the fact that no one who had not read him in the original could really be said to have known his works in the proper sense, this intelligent and sensitive woman was able to make allowances for what was being lost in the translated versions of his writings and to fill in some of the gaps with her shrewd guesses based on her direct interaction with him in life. While her knowledge of English was clearly an asset in her communication with him, her not being a direct heir of British imperial culture prevented the negative aspects of that culture from rubbing on to her and interfering with her appreciation of the great Indian. She was able to bypass all that politics without any problems and recognize in him a great writer who, if readers could only open to him, could move them profoundly and also offer rich philosophical insights that could inspire, comfort, nourish, and sustain them as human beings. Ocampo has always insisted that good literature must have the capacity of growth within us, like a living organism, like a child in the womb. Tagore’s works had this capacity. They took roots within her being. His ideas and images spread their branches and leaves in her own activities. Tagore opened her intellectually to a whole world of Indian thought, gave her new conceptual tools like the word dharma, which she used effectively in her own writings. The influence of Indian thought can be seen clearly in her allegorical play La laguna de los nenufares (‘The Pool of Water-Lilies’), written before her direct encounter with Tagore. If this play were to be translated into Bengali, it could be passed off as a ‘lost play’ of Tagore, so strong is its spiritual similarity to Tagore’s world.

The opening up to India meant that Ocampo also became an admirer of India’s other great son of that time, Gandhi. She heard him speak once - in France. These two great sons of India attracted her with almost equal power, though temperamentally she was closer to Tagore. Her attitude to Gandhi was not one of uncritical veneration. She could not accept his harsh asceticism, and this failure to accept him in entirety tormented her, because she wanted to accept his teachings in a total sense, but she deeply appreciated and respected his teachings on non-violence and the moral example he set to the contemporary world. In fact, her friends affectionately remember her as being violently in favour of non-violence! We may say that her dharma permitted her to appreciate two such different personalities as Tagore and Gandhi. She has written several essays on Gandhi, some extracts from which I have presented in Bengali translation in my Rabindranath o Victoria Ocampor Sandhane. It was not a passing interest. Her respect for the essence of Gandhi’s teachings only increased with the years. She influenced the thinking of her friend Aldous Huxley in this respect, changing his attitude to Gandhi from one of indifference to one of deep admiration. She defended Gandhi against slanderers to the end of her days, writing articles and letters to newspapers. Her admiration of Gandhi also opened the door to her appreciation of another rare character, T. E. Lawrence or the Lawrence of Arabia, about whom she wrote a perceptive little book. From her admiration of Tagore and Gandhi she also went on to become an admirer of Jawaharlal Nehru, and eventually, of Indira Gandhi. The fact that a woman became the prime minister of a vast country like India roused a deep feminist enthusiasm in Ocampo, and she wrote about it. When Mrs Gandhi went to Buenos Aires, she went to see Victoria Ocampo before paying any of her formal official calls. All these events have happened in a chain as consequences of Ocampo’s initial discovery of the French Gitanjali in 1914. Thanks to this chain, there is a lot of goodwill in Argentina toward India. When I was there, ordinary people came up to me and spoke to me - about India, about Mrs Gandhi, about nuclear disarmament and the non-aligned nations, about Richard Attenborough’s film on Gandhi, about the film version of A Passage to India, and so on. I saw writings on the walls which effectively said: ‘We loved you, Indira, but they assassinated you.’

Tagore and Gandhi together made Ocampo realize that there was nothing to stop a country like India from becoming a spiritual fatherland to a Westerner like herself. To her French friend Andre Malraux, India or Asia symbolized ‘the Other’; but to her India revealed her own authentic spiritual identity. Ocampo had been brought up in the Catholic faith, but had rejected the harsh teachings of the Catholic Church. Gandhi made her go back to the essence of the teachings of Christ; the Gitanjali directed her to the Bhagavadgita, from which she went on to the Spanish mystic St. John of the Cross. Thus India helped her to re-appreciate her own Western heritage.

Fig 17: Tagore standing in front of Miralrio, with the famous balcony behind him and the tipa tree to his right. Tagore and Ocampo shared similar attitudes in many areas of life: to nature, to freedom, to religion. Both loved trees, light, and wide, open spaces. In Tagore this love was nurtured by the landscape and riverscape of Bengal, in Ocampo by the Argentine pampas and the broad expanse of the Rio de la Plata. Both believed in the kind of religion that springs from the depths of our own lives and is not just based on scriptural texts and institutional rituals. Both had admired the dramatic expression of passions in Shakespeare’s plays in their youthful days. These resonances enabled Tagore’s influence to become quite radical in her life. When the two first met, Ocampo was still too inexperienced to understand all of Tagore’s messages in their fullness, especially their political dimension. But as she suffered and matured, she understood the full meanings of his statements. In her career of an internationally minded cultural entrepreneur, dedicated to the promotion of liberal, cosmopolitan, humanistic values, and to the building of cultural bridges between nations and continents, she was deeply influenced by Tagore. When she first met him in 1924 she was just an emerging young writer who had only published one book and a few articles. In 1931, the year after her second meeting with Tagore in France, she launched her magazine Sur (meaning ‘South’). The idea of starting a magazine was put into her head by the North American writer Waldo Frank. The magazine as Ocampo developed it was not quite the pan-American mouthpiece that Frank had envisaged, but it did become the most important literary magazine of its time in Latin America. In its ideal of cultural cosmopolitanism the magazine was very close to Visvabharati, about which she had heard Tagore speak in Argentina. She also saw some issues of Visvabharati Quarterly and it seems she subscribed to it at least for a limited time. It could be said that Visvabharati acted as a distant paradigm for Sur. A galaxy of well-known Americans and Europeans contributed to it. It was through this magazine that a distinguished group of Argentine writers like Borges, Bioy Casares, Silvina Ocampo, Eduardo Mallea, Martinez Estrada, Alberto Girri, Juan Jose Hernandez etc. emerged after the Second World War. To her magazine Ocampo added a publishing house, also called Sur, which published not only books originally written in Spanish but also translations from contemporary French and English works. Ocampo herself translated Albert Camus, T.E. Lawrence, Graham Greene, and Dylan Thomas. One of her special achievements through her magazine and publishing house was to make modern literature written in English, from Britain and North America, widely familiar to South Americans. This familiarity had a tremendous impact on many creative minds. Distinguished writers from Peru, Colombia, and Mexico have testified to the reality of this impact.

What made Ocampo’s achievements even more heroic was the period in Argentine history in which she established her magazine and publishing house. It was in the beginning of the thirties, when the high hopes of the twenties gave way to the ascendance of military power and the erosion of democracy. It was against a backdrop of encroaching fascism that she emerged as a champion of liberal values.

Victoria Ocampo herself became an important essayist, and when I was working on her there were ten volumes of her essays available, called Testimonios, but not every essay written by her had yet been anthologized. She wrote other books too, on Virginia Woolf, T.E. Lawrence, Keyserling, and of course the famous Tagore en las barrancas de San Isidro. Her posthumously published memoirs in six volumes also contain memories of Tagore in two of the volumes. I think that Tagore’s own autobiography and various of his autobiographical essays on his childhood and education influenced Ocampo’s own autobiographical modality, which was central to her self- expression.

She became an important cultural patron in Buenos Aires and was involved in many important activities such as bringing good contemporary European music and ballet to her city, combating fascism in Argentina, helping the resistance in Europe before and during the Second World War, giving shelter to refugees fleeing fascist persecution in Europe, and the feminist movement. Her liberalism and anti-fascism brought her the wrath of Peron, under whom, in 1953, she was held in prison for 26 days. There were protests from her many distinguished friends and admirers all over the world, including the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral and India’s Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. She was released. In fact, the international network of her friendships was in itself quite an achievement. A great deal of her work as a cultural organizer was made effective through this network. She had many friends among the writers, artists, and intellectuals of London and Paris and of the USA in the thirties, forties, and fifties. Men like Graham Greene, Aldous Huxley, Albert Camus, Roger Caillois, Ernest Ansermet, and Igor Stravinsky were good friends of hers. She also cultivated a somewhat one-way relationship with Virginia Woolf. Very much like Tagore, she wanted to bring the best of the whole world to her compatriots, like a banquet to be shared, though unfortunately she also lived to see cultural cosmopolitanism get steadily eroded over the decades.

Her final statement on Tagore, in which the relationship is elevated to its maximum sublimation, is contained in Tagore en las barrancas de San Isidro, written in 1958 for the forthcoming Tagore centenary and dedicated to their common friend Elmhirst. In 1961 she helped to celebrate Tagore’s hundredth birth anniversary on a grand scale in Buenos Aires. Quoting the Upanishads, she has said that Tagore helped her to pass from the unreal to the real, that the lessons she learned from men like Gandhi and Tagore were for her like a restitution of riches which she had inherited without knowing that she had inherited them. If Ocampo became a distant Muse for Tagore, he too became a radiant source of energy for her. In 1941, after Tagore’s death, she said: ‘I guard everything I learned from him so that I may live it. So that I may live it as long as my strength permits me.’ It could be said that she strove to keep this pledge throughout her long life, through many struggles, so that her life’s work was in a sense a monument to the man she called her guru, the teacher who showed her the way. Many have addressed Tagore as Gurudev, but perhaps few have earned the real right to call him so as have foreigners like Elmhirst and Ocampo, who have actually been deeply influenced by Tagore’s ideas in their careers in their own countries. Tagore’s warnings against the dangers of aggressive nationalism burst into meaning for her with the emergence of fascism and the outbreak of the Second World War. The full implications of his messages on the value of freedom and the evil of tyranny became clear to her only when his experiences as a member of a subject nation were matched by her own experiences of despotic rule in her own country, culminating in her imprisonment in 1953.

The friendship between Rabindranath Tagore and Victoria Ocampo, with the influence each had on the other’s work despite the distances that separated them and the gaps in communication that existed between them, constitutes a rich and beautiful story of the meeting of like minds. Because they were who they were, the story is a meaningful chapter of literary and cultural history. It is also the kind of human story which has the power to cheer and inspire posterity, from which others can learn: not only how such friendships can be initiated and built, but also how the model offered may be improved on. It is a modern story, and a story of hope, with many resonances in the minds of modern men and women. That they were at all able to make something out of their relationship surprises some; that they were able to draw so much out of it indicates the extent of the creativity of each. The erotic attraction was probably the crucial factor that enabled them to elicit so much out of the relationship against so many odds. The paradox of such attraction is that while it is always a risky business, the dangerous element of a relationship, what always causes much pain when the yearnings are not fulfilled or when the friends are separated, and what can become destructive if there is rejection or humiliation, it nevertheless lends itself, even in difficult circumstances, to being converted into the energy that can fuel creative activity.

I hope that Alfonso Chacon R. and Rajat Chanda will be able to correct the errors in their articles in the light of what I have written above and the published books. *

It must be remembered that Argentina was for Tagore a mixed experience. He was happy to meet an ardent fan like Victoria, but he was disappointed in other ways. He did not find intellectuals with whom he could hold a dialogue, who were interested in his ideas and ideals on education. He had expected to see a synthesis of native Amerindian and European cultures, but found a culture that was excessively dependent on Europe. In this respect, as I have already indicated, Argentina was not a typical representative of Latin America, and Tagore received an incomplete idea of Latin America from his visit. Tagore’s negative reactions and Ocampo’s own reactions to them when she found out about them are discussed at some length in Chapter Eleven of my book In Your Blossoming Flower-Garden. Alfonso Chacon R. raises some problematic issues regarding Sarmiento, which I am not really in a position to judge. I am aware that Sarmiento was in favour of Europeanization, but did he proclaim ‘the need for the extermination of the Native Americans’? Physical extermination? Certainly, Sarmiento, who was a friend of Victoria Ocampo’s great-grandfather, is to this day regarded as an important thinker, statesman, patriot, and educationist in Argentina. Victoria Ocampo wrote on him and she has even been compared to him.

I am aware that Ocampo had an ambivalent reputation in both right-wing nationalist and extreme left circles in Argentina. I have discussed this in my English book. Some called her a ‘foreignizer’; others could not forgive her for being a daughter of the oligarchy. But people can’t help their birth. And she spent her inherited wealth in the service of her nation’s culture. Her texts consistently reveal enlightened, humanistic, and humane attitudes. Ocampo did not deny the Amerindian heritage of Latin America; nor did she repudiate Argentina’s solid links with Europe. She claimed Europe’s culture as part of her heritage too. If she did not have cosmopolitan values, she would not have taken such a profound interest in Tagore’s works and ideas in the first place. Indeed this broad cosmopolitanism was something that Tagore and Ocampo had in common. If Ocampo’s class was Europe-oriented, then Tagore also, we must remember, was an offspring of the Bengal Renaissance, which was triggered off by the contact of the Bengali upper classes with European ideas and texts. This gave them a common ground.

I myself feel a deep affinity with Ocampo’s tendency to regard what is great and good in another culture as her heritage also. I too share her attitude in this respect. I felt that her works were my heritage too, which I was prevented from accessing because of not knowing Spanish, and that’s why I taught myself Spanish to read her. Ocampo does not belong to Argentina only; Tagore does not belong to India only. They belong to all the world, whoever cares to read them. That, surely, is the way forward in today’s world. Isn’t that why we have been deeply shocked by the destruction of the Buddhas of Afghanistan?

In another small but important respect Latin America left a deep mark on Tagore. Tagore took a genuine interest in the art of the Amerindians. That’s why he was vexed at not being able to proceed to Peru and Mexico. But he did look carefully at museum collections and at reproductions in art books. He expressed a deep interest in the art of the Incas and his sadness at the destruction of Inca objets d’art. When he was in Miralrio somebody called Reeves came to have tea with him and show him books about the Incas. While in Argentina, he also spent some time examining a rich collection of Quechua images and textiles owned by a Senor Barreto. He was fascinated. The Kala Bhavana Library in Santiniketan still holds a richly illustrated book called The Art of Old Peru (1924), which could have well accompanied him on his voyage on the Andes that year, when he started the doodlings in the famous ‘Purabi manuscript’. The forms and motifs of Peruvian, Haida, and Tlingit artefacts have definitely influenced Tagore’s art. I became more sharply aware of these influences in course of a later research project which I initiated, and they are discussed in detail in the book Ronger Rabindranath (Ananda Publishers,1997), which I wrote in collaboration with Sushobhan Adhikary of Visvabharati and other scholars.

Casting Ocampo’s enthusiasm for Tagore in a broader perspective, we can now return to the subject of the extraordinary popularity which Tagore achieved in the Spanish-speaking world through the Jimenez re-translations. The Jimenez connection with Tagore has been studied in detail in the book Sasvata Mauchak by Sisirkumar Das and Shyamaprasad Gangopadhyay (Papyrus, Calcutta,1987). The great success of the Jimenez re-translations was certainly due to the genius of Juan Ramon Jimenez as a creative literary translator. He was able to re-create Tagore for Spanish-speakers. He was also himself deeply influenced by Tagore. However, we must not forget that Jimenez, with the invaluable help of his wife, who knew English well, translated from the English versions available to them, not from the original Bengali. We do know how problematic those old English translations are, how uneasy their relationship to the originals is, especially in the poetry. So many of the translations are truncated paraphrases of the original poetic texts, robbed of their beauties. It is therefore true to say that though speakers of Spanish have come to admire Tagore through the versions prepared by the Jimenez team, they still have an inadequate idea of what his texts are really like; there is now scope, and indeed, a need for them to open a new chapter in the history of their reception of Tagore. To study him in any depth, it is necessary to know Bengali, both to read him and to access vital critical material. A few Spanish and Latin American literary people must now show their commitment to cosmopolitanism by learning Bengali and translating him directly from the original Bengali texts. They will discover a kingdom full of rich resonances for them. It does surprise me that a few such translators haven’t yet emerged. If I could learn Spanish in my forties in order to read Victoria Ocampo, surely a few speakers of Spanish could learn Bengali in order to read Tagore in the original.

The lack of authentic translations from the original texts is a problem that has bedevilled Tagore’s reception even in those countries which sport Tagore fans. Jorge Luis Borges, the noted Argentine writer who belonged to the Sur circle, is well-known for his notorious joky comment that Tagore was ‘a hoaxer of good faith or, if you prefer, a Swedish invention’ (referring to the Nobel Prize). Victoria was furious and leapt to Tagore’s defence even at the age of 82.

Tagore is also popular among speakers of Portuguese. Recently I have had the pleasure of meeting Jose Paz, a scholar and teacher who is a native speaker of Galician-Portuguese and an ardent admirer of Tagore with a special interest in his educational ideas. He is attached to the University of Vigo and with the zeal of an authentic bibliophile is building a library for Tagore studies in his native town of Ourense in Galicia in northern Spain. According to him, translations of certain Tagore texts directly from Bengali into Galician-Portuguese have been done by Telo de Mascarenhas, who knew Bengali. These, says Paz, are superior to the versions done by the Jimenez couple. In a paper presented in a conference in London in October 2000, Jose Paz quotes from Octavio Paz’s book Vislumbres de la India (‘Glimpses of India’), based on his experiences as Mexico’s ambassador to India. Octavio Paz is quoted as saying that Tagore was ‘not a thinker’, but ‘a great artist’. Jose Paz does not agree with this assessment. He says: ‘Besides being a great artist, I think he was also an exceptional thinker.’ Jose Paz also points out that certain Spanish and Latin American writers have made negative comments on Tagore’s works, ‘probably, or certainly, because they have not read them’. According to him, ‘the Spanish writer Francisco Umbral and the Colombian writer Garcia Marquez do not like Tagore.’

That bemuses me, especially when set against the connection Alfonso Chacon R. makes between the influence of Tagore in breaking down the boundaries between poetry and prose, and the so-called ‘Latin-American literary boom’. Alfonso says, ‘It seems funny then to hear some literary critics browbeat some current Indian writers, accusing them of imitating Latin American styles like Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “magic realism”, without realizing that, to a certain extent, they are just returning to India’s greatest literary figure.’ Life is full of unexpected twists and turns, one event leading to another and producing results that were not anticipated. The erasing of boundaries between poetry and prose initiated by Tagore is known to have affected Icelandic writing as well. But the majority of those trendy writers of ‘Indian English fiction’ who emulate ‘magic realism’ do not really read Tagore, and judging from Jose Paz’s remark about Marquez, one cannot be sure if the Latin American magic realists do that either.

What about the other side of the coin? The poetry of Lorca or Neruda enjoys a certain vogue among Bengalis, again mainly through English translations and Bengali versions which, I suspect, may be done with the help of the English versions. The eminent post-Tagore poet Bishnu Dey, who has translated poetry from a diversity of languages, usually via English and often, as acknowledged by his widow, with the help of linguist friends, has translated poems by both Lorca and Neruda. The translations certainly read well. I think other poets too have done similar work from time to time, but I haven’t got enough samples at hand here in England to make meaningful comment on such work. There are some elegant translated fragments from Juan Ramon Jimenez in Das and Gangopadhyay’s book Sasvata Mauchak, mentioned above.

Bengalis are certainly good linguists, so I hope there will be more translations from Spanish writings into our language in the future. Unfortunately, there is a split of interests between those who manage to acquire a foreign tongue and those who pursue literary careers. The two interests need to overlap to some extent for good literary translators to emerge. Bengalis who pursue literary careers tend to live and work in areas where it may not be all that easy to acquire Spanish. On the other hand, students who acquire Spanish in an elite institution like the Jawaharlal Nehru University of New Delhi are likely to do so for a specific purpose such as going into the diplomatic service. They may not necessarily be interested in literature. Considering the flirtation with revolutionary ideas that is a feature of Bengali intellectual life, one might have expected that a few more Bengalis might have picked up Spanish by now simply in order to read the left-oriented poets of Latin America!

It should be easy enough for some of the diasporic Bengalis from both India and Bangladesh to pick up Spanish, especially in the USA, where Spanish is spoken by so many. To be effective as translators, though, they must not lose their Bengali in the first place. I think I have occasionally seen articles in Jijnasa which indicate that this process of acquisition may be slowly happening.

As for me personally, the Tagore-Ocampo work has been a milestone in my life. My reward for persevering with Spanish was my own encounter with a woman whose radiant spirit was still alive in everything she had written and in the testimonies of those who had known her well. I have learnt so much from Victoria Ocampo: from her courage and fighting spirit, and her capacity for love and admiration. I regret not having met her while she was alive. I have given talks about her and Tagore in various venues such as the London conference on Tagore in 1986, the University of Gujarat in Ahmedabad (1989), Visvabharati (1983 and 1992), and the Centre for Cross-Cultural Research on Women at Oxford (1990). The last occasion was a gathering I organized myself to honour the centenary of Ocampo’s birth.

Inevitably, my interest in Spanish and my own research trip to Argentina have had other kick-offs. I have been interested for a long time in the songs preserved in the Judaeo-Spanish dialect known as Ladino, and six songs translated from the Ladino occur in the fictional part of Rabindranath o Victoria Ocampor Sandhane, two more in my second play (to be sung in Bengali to the original Judaeo-Spanish tunes). I have also published in Jijnasa translations of a few poets I met in Argentina, including Manuel Asorey and Rafael Felipe Oterino. One of my own English poems was translated into Spanish and published in a Buenos Aires magazine entitled Empresa Poetica. And I have written a series of poems in English remembering my time in Argentina which have been included in my collection Memories of Argentina and Other Poems (Virgilio Libro, 1999).

* I would emphasize the following points:

1. Victoria Ocampo cannot really be called a poetess. That is a misconception. Her prose is very poetic, but she is essentially an essayist and a great writer of memoirs. She is also a superb letter-writer.

2. Tagore did not write all of the Purabi poems in Argentina, only about a third of them. The rest were written before he arrived there.

3. Tagore did not stay in Ocampo’s own estancia. He stayed in the rented Miralrio. But he and Elmhirst visited Villa Ocampo, her parents’ residence a few blocks away. Incidentally, I must mention that I have occasionally come across a strange notion prevalent in certain circles that the house in which Tagore stayed in Argentina was blown up and no longer exists. An ex-ambassador of India to Argentina has even chided me in print for saying that I have visited this house. I am happy to confirm that Miralrio very much exists, and that I did visit it!

4. I am not sure why Victoria’s name has been written Vittoria in Chanda’s article. Vittoria is the Italian form of the name.

5. Victoria turned to writers and writing not so much to ‘free herself of the oppression of loneliness’, as Chanda puts it, as to do something exciting with her life, to express herself and use her energies. She wanted to be an actress, but that wasn’t allowed.

6. Victoria obtained a ‘legal separation’ from her husband, not the full divorce.

7. The Tagore-Ocampo letters have been available in full since 1988 in my book In Your Blossoming Flower-Garden. Quotations in Chanda’s article need to be checked against the book and their dates correctly given. There is some confusion both about when certain letters were written and about what was said in them. In one place he says, ‘Years later, he [Tagore] wrote from Santiniketan’ etc when in fact Tagore wrote that letter in December 1925, just one year after his visit to Argentina.

8. Tagore did express nostalgia for the villa in San Isidro, but to claim that he ‘expressed the desire to return to Buenos Aires several times’ gives the wrong picture. Tagore also made plans to meet Victoria in an Italian villa; he also asked her to come to Santiniketan.

9. In the last year of his life Tagore wrote two poems about the chair given to him by Victoria. And there are certainly more than two poems in which Victoria is directly addressed (‘Atithi’, ‘Ashanka’ and ‘Shesh Basanta’, for example). She is never addressed by name, but it is clear that it is she who is being addressed. Several other poems can be connected to her. The fifth poem of Shesh Lekha from which Chanda quotes is actually one of the two poems about the chair; it refers to her, but is not directly addressed to her. For Latin American readers who may be interested, ‘Atithi’ has been translated by William Radice in his Selected Poems of Tagore (Penguin, 1985), and I myself have translated both ‘Ashanka’ and No. 5 of Shesh Lekha, as well as a few other poems that have a connection with Victoria, in my Selected Poems of Tagore (Bloodaxe Books, 1991).

10. I am not sure that Victoria re-translated Red Oleanders into Spanish. She began translating the English text into French, but the work was either not finished or not published.

Published July 15, 2001

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us