-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Rabindranath Tagore | Essay

Share -

Tagore’s Message On Religion: What Does it Mean to Me? : Sukhendu Dev

©Harris Manchester College, Oxford* Oxford, England May 3, 2010

I have been to this city many times, but only as a visitor, during my long 16 years’ of stay in Britain. This is the first time I am here to do some research for a few months. The readers may be asking why this special note. Many of Tagore’s fans normally celebrate his birthday, May 7; especially in places like Kolkata with readings of his poetry, singing his songs, staging plays he wrote. To me, however, the best way to celebrate Tagore is to reflect on his ideals which are so very universal in nature. I was struck by this thought as I crossed the road from the Balliol College dorm where I stay and saw a building called Harris Manchester College. I had to go in, since I immediately remembered reading, a long time ago, Tagore’s slim volume, The Religion of Man, which contains the Hibbert lectures, an annual event where leading scholars were invited to give “non-sectarian lectures on theological issue.” Tagore gave these lectures at Manchester College (as it was known then), Oxford, way back in May, 1930. It is interesting to note that Radhakrishnan, who was the Spalding Professor of Eastern Religions and Ethics at Oxford University, also gave the Hibbert lectures the year before, in 1929, titled, “An idealist view of life.” It is almost 80 years now, but Tagore’s message on religion resonates so very clearly even today that, if only we could follow it in the spirit he talked about, we would most probably see far less strife than we do in our world of today.

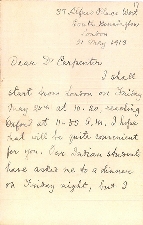

Tagore's letter to Dr. Carpenter-1* (Click to read in full)

Getting inside any of the libraries—Oxford University has many, the most famous being the Bodleian, which has books and manuscripts that are not available anywhere else in the world—is almost impossible without a valid university ID card. Fortunately, mine arrived not long after my arrival here about a month ago. I rushed inside the library and asked the Fellow Librarian to help me search for the documents during the time Tagore gave the lectures. She was very kind and spent a considerable amount of time digging out hard bound volumes that went back to around 1910. I pored over every page looking for evidence of any special notes or correspondence Tagore had with the Principal of the college at the time, Dr. J. Estin Carpenter. I did not see any correspondence written in the 30’s but, sure enough, three letters were tucked away in Tagore’s handwriting written between May 3rd and May 21st, 1913, from South Kensington, London. Although not historically important, these letters were precious to me—just to see the letters written in Tagore’s own handwriting. I read and re-read them and took copies. In one of the letters (May 9, 1913), Tagore wrote, after having accepted an invitation to stay in Dr. Carpenter’s house, “It is beyond my power to hold any divine service in English but if Bengali would suit my countrymen you can fix a time on Sunday 25th.” Then on May 21st, he wrote, “Our Indian students have asked me to a dinner on Friday night, but I do not know if that will interfere with any arrangement that you may have made and I have requested them to ask your permission.” Having succeeded in my very first effort to find these, I went to the Indian Institute Library only a few yards away, and it was absolutely overwhelming looking at their collection. No wonder, so many Indian students still come here for their graduate work on India!

Tagore's letter to Dr. Carpenter-2* (Click to read in full)

What about Tagore’s message? Although the book by itself is not too long, The Religion of Man had 14 chapters excluding the conclusions. The names of these chapters themselves suggest Tagore’s deep thinking as to how he viewed religion. It starts with “Man’s Universe,” and ends with “The Four Stages of Life,” with chapters in between such as, “The Vision,” “The Music Maker,” “Spiritual Freedom” etc. It is not my intention to elaborate on all this but, personally, I got the sense out of these chapters that the very essence of religion is its universal message which is deeply embedded in them, irrespective of any race and creed. Tagore was emphasizing the fact that while there is nothing wrong in looking for materialism that is so prevalent in the West, and its immense progress in science, we must not lose sight of the divine. I could not agree more when he said, “the God of humanity has arrived at the gates of the ruined temple of tribe.” For him there is no more inhibition and he has arrived at the truth. The book encapsulates, he says, the gist of many lectures he has given throughout his life in many countries over a very long period and is not “merely as a philosophical subject.” They are all “linked by a unity of inspiration.” In one of the past issues of Parabaas, Kathleen O’Connell, while writing about the Utsav-Celebration, has discussed Tagore’s approach to “cultivating the human spirit and the study of religion,” a topic not so dissimilar to our current discussion.

Tagore's letter to Dr. Carpenter-3* (Click to read in full)

In Chapter VII titled “The Man of My Heart,” Tagore says, “At the outburst of an experience which is unusual, such as happened to me in the beginning of my youth, the puzzled mind seeks its explanation in some settled foundation of that which is usual, trying to adjust an unexpected inner message to an organized belief which goes by the general name of a religion.” He goes on to say, “After a long struggle with the feeling that I was using a mask to hide the living face of truth, I gave up my connection with the church.” The church Tagore is referring to was a monotheistic church where his father was the leader and Tagore was asked to be the secretary by his father. I have often wondered, after reading this, how many of us in our youth have been asked by our parents to come to many ‘pujas’ which we did, many times rather reluctantly, but, now in retrospect, I know I never understood the real significance of religion.As a working scientist, the chapter, “The Four Stages of Life,” appealed to me greatly, especially when he writes, “For science may truly be described as mysticism in the realm of material knowledge. It helps us to go beyond appearances and reach the inner reality of things in principles which are abstractions; it emancipates our mind from the thraldom of the senses to the freedom of reason,”— the best description I ever read of a link between mysticism and science. Talking about science and freedom, Tagore goes on to say, “The final freedom of spirit which India aspires after has a similar character of realization. It is beyond all limits of personality, divested of all moral or aesthetic distinctions; ….. Though science brings our thoughts to the utmost limit of mind’s territory it cannot transcend its own creation made of a harmony of logical symbols. In it, the chick has come out of its shell, but not out of the definition of its own chickenhood.”

Differentiating between science and religion, Tagore says, “As science is the liberation of our knowledge in the universal reason, which cannot be other than human reason, religion is the liberation of our individual personality in the universal Person who is human all the same.” Beautifully put and a true eye-opener! It goes way beyond what Francis Collins, a leading geneticist, who headed the Human Genome Project and wrote a book, The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief. I may be wrong, but I doubt very much whether Collins ever read The Religion of Man.

I remember writing an article (The changing face of biology, Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 1997, vol. 22, 29-36) before the human genome was sequenced, on a rather speculative topic, namely, where biology was going to go in the next 20 to 50 years. Under the subheading, “Message of Universality,” I said: “I may have missed it, but I have not come across any in-depth discussion of one particular aspect of this discovery. I like to call it the ‘Grand Unification’ aspect. What I mean by this is the following: it was the first time that one could see instantly that the life process, irrespective of its source, has a single origin, in the long string of four letters, A, C, T, and G in an intertwined double helix. It is unbiased: race, color, creed, and religion independent. It transcends all kingdoms—animal, human, plant, and bacteria. One is left with this sense of wonder that, in the scheme of things, all living objects owe their existence to those two strands. By any criterion, this signifies unity in nature. One may sense here a philosophical undertone, but an abstraction it is not. It is real; it can be seen and touched. It can be quantified.”

But, I realize this is not the kind of message that most people can interpret as unity in the broadest sense. However, while reading The Religion of Man, it is clear what he espouses is his message that is buried deep in his heart. He says he offers here “the evidence” of his “own personal life brought into a definite focus.” In a sense, though, we all need to bring together our images that are often very blurred in our mind and our wavering thoughts that buffet us every day of our lives into, not only definite, but also into sharp focus.

I think it is most appropriate that, reviewing the book, News Chronicle said, “Rich in profound thoughts and poetic speech ….. he has never written anything so penetrating and illuminating on the nature of things ……..Dr. Tagore has seen visions, and he can paint them for us with a compelling charm due to utter simplicity and fidelity.”

This is not an isolated example of Tagore’s writings but, analyzed properly, I found many of his ideas were far ahead of his time. If only we could get into the inner meanings that he was striving at, the world would be a much better place. It is time that we looked at Tagore’s writings in a new perspective in relation to what is happening in the world. If we did that in an unbiased way, without pre-conceived ideas and prejudices, we would most probably come to a deeper understanding of the workings of the human mind, irrespective of which part of the world we come from, and provide the kind of leadership in all spheres of life that we so badly need. We need to go beyond the culture of “individualism” that is so paramount in the West and attempt a true unification of our inner values and virtues.

©Harris Manchester College, Oxford*

Acknowledgement: I am deeply grateful to Sue Killoran and Katrina Malone for their help in finding and scanning not only the attached letters, but also the two old photographs of Tagore, one by himself, and the other in a group with Radhakrishnan, from the Harris Manchester College Library, MS J. E. Carpenter 6 folios, 13-18 (letters). Thanks also to Ms. Killoran for reading the draft and for some editing.

*Photographs and images of letters are copyrighted to Harris Manchester College, Oxford. Reproduction in any form without prior permission from the College is strictly prohibited.

Published in Parabaas May 9, 2010; 25-she Boishakh; 1417.

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us