-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | English | Novel

Share -

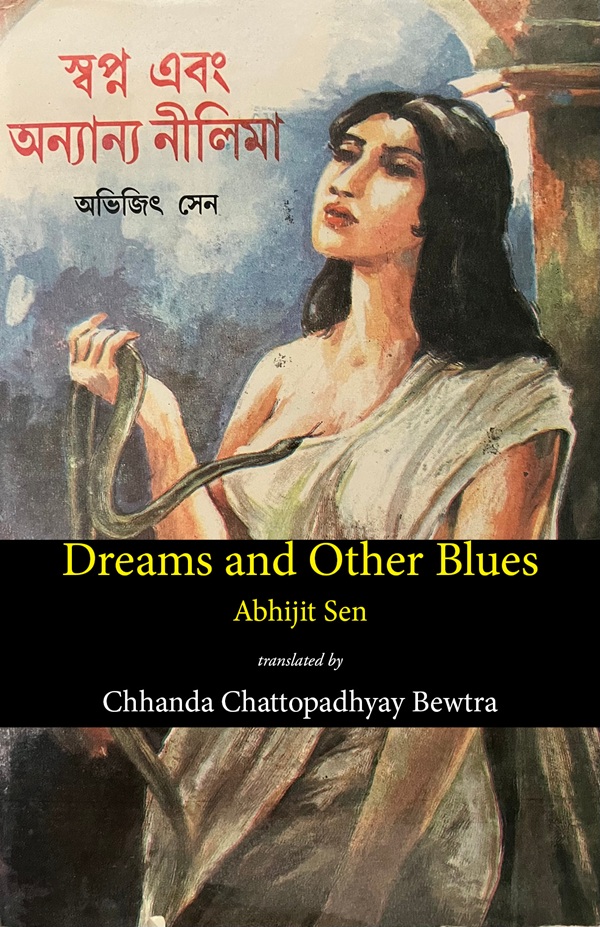

Dreams and Other Blues (2) : Abhijit Sen

translated from Bengali to English by Chhanda Chattopadhyay Bewtra

Abhijit Sen's novel স্বপ্ন এবং অন্যান্য নীলিমা (Dreams and Other Blues) first appeared about 28 years ago in a special issue of Pratikshan. After considerable revision, it was published as a book in 2000 by Dey's Publishing, Calcutta.

Abhijit Sen's novel স্বপ্ন এবং অন্যান্য নীলিমা (Dreams and Other Blues) first appeared about 28 years ago in a special issue of Pratikshan. After considerable revision, it was published as a book in 2000 by Dey's Publishing, Calcutta.

3.Sati, whose formal name was Farida Mansur, and who had a charming style of adaab, as Saroj noted earlier, was the eldest daughter of a refugee family uprooted from East Pakistan. Her younger sister Hena was equally beautiful but, unlike Sati, more talkative. We shall know more about her later.

It’s unusual to find beauty without vanity. Sati belonged to that rare group. Her beauty shone like a soft fluorescent light whose source remained hidden, but it lit up all the surroundings. People often did not notice it right away.

Sati had graduated from Dhaka University in 1965. She got married a year later to a wealthy man with fast money. He accumulated his wealth from shrimp export, hotel dealership, and tourism. From the very beginning Sati had disliked his lifestyle. He was a Muslim but indulged in many sins outside his religious edicts.

Sati had gone to Calcutta to learn Rabindra Sangeet. It was not yet popular at the end of the '60s. One had to struggle hard to earn the right to one’s own language and culture. The youth, students, and the intelligentsia waged the battle in those days. Even though not universally popular, the historic events that took place in that period did affect many, but Sati’s husband Abu Hena was mostly untouched.

Unexpectedly hearing his old name, Saroj was startled. He couldn’t decide how to answer her.

His reaction did not escape Sati. She tried to interrupt his denial and said immediately, “Of course, if you have any objections, we don’t need to get into it. So many things happened to so many people in the last few years in our subcontinent...”

She was tactful in her last sentence, though Saroj could not detect any trace of cunning in her face. The disaster and lack of sleep had darkened the skin around her eyes, as if she had cried and rubbed her eyes continuously. The large eyes, deep and sincere, were upon him now, eager but patient, poised like a dancer’s.

Saroj looked into those eyes to guess her real motive. Then his gaze slipped down her body. Just as Sati uncomfortably pulled the end of her sari around her, he looked away.

The word ‘subcontinent’ had suddenly become very political. Sati’s words made it clear that she knew the political meaning and usage of the word.

Pulling the sari over the right shoulder to cover the breasts was also a typical act of modesty in the subcontinent. Sati felt shy as Saroj looked away. Covering herself in front of someone casts undue aspersions on that person. The women of the subcontinent knew that too.

Saroj said, “No, I mean, objection--” He got confused and stopped.

Indeed, who was he? Was he Manik? Or was he Saroj? Wasn’t he Manik? Or wasn’t he Saroj?

Sati’s words, ‘in the last few years’, meant the seventies in the political background of the subcontinent, literally, the seventh decade of the twentieth century. That decade was a critical period: Charu Majumdar had called to turn it into ‘the Decade of Liberation’. Of course, historic eras cannot be categorized neatly into decades. The stormiest period of Charu Majumdar’s movement occurred in the last three years of the previous decade.

In Sati’s own country, many directionless movements merged into a volcano spewing out all the passions and expectations of the people. It was not just a storm anymore. It was a storm, flood, and fiery eruption all together.

Sati’s words, ‘people had so many things happen...’, also weren’t meant in the ordinary sense. Manik didn’t have to change his name to Saroj in ‘ordinary’ times. Saroj looked at Sati and forgot his secrecy. He said, “No, I mean, have you seen me before somewhere?”

Sati’s family of four had arrived only a few days before. There was Sati, her sister Hena, who was five or six years younger, her mother Rumela, who was in her fifties, and their uncle Abdul Kuddus, just over sixty. Saroj’s refugee camp was in a schoolhouse where he had designated for their accommodation a part of one classroom already occupied by fifteen to sixteen members of four other families. Saroj himself wasn’t comfortable with the arrangement as the residents were mostly rural farmers, not of the same class as Sati’s family. There were possibilities of conflicts. Elsewhere, such conflicts had ended in physical violence, even bloodshed.

But these days, nobody has had time to worry too long about such problems.

Still, the issue about Sati’s family had worried Saroj.

The main reason was that Sati’s folks were of the same class as Saroj.

Sati and Hena were both attractive women. Even the current calamity, uncertain future, exhausting journey, and other horrible experiences had not erased their beauty. Saroj himself had been inspired by Communist idealism since his childhood. Working along with the movements for the last four or five years, he had tried to make himself classless and thought he had succeeded in it. But now he realized the matter wasn’t that easy. Perhaps impossible.

“In Calcutta.” Sati held her eyes like searchlights on his face.

“Calcutta!” Even the most minute search could not dredge up any memory in Saroj’s mind. Still, he felt quite excited.

“I first listened to your speech in '67, in the Institute Hall of the University. We also met a few times later.”

Saroj tried to remember. Even though he could not recall anything specific, he was pleased to realize that was perhaps why she looked familiar earlier.

He said, “Strange! After so many years--”

Alamgir Mansur, Sati’s father, grew up in a government worker's family. Her grandfather Jiad Ali was an ordinary clerk in the government office in Dhaka. Extremely religious, his strong sense of self-respect and pride had kept him from becoming one of the newly rich folks during the turmoil of independence and partition. Out of his six offspring, the first five were girls. The sixth child, Alamgir, followed his father’s wish and became an officer in the Bengal Civil Services. In those days, a government officer was like a god to the ordinary clerks. Other jobs did not separate officers from clerks so widely. Indeed, in this subcontinent, the words ‘sahib’ and ‘officer’ meant these government officers, who wielded more power and prestige than the officers in banks and insurance companies, as well as professionals in engineering, medicine, academics, or research. Even within the government, the non-administrative branch was lower in the pecking order. The administrative officers were the big bosses, the heirs to colonialism, often treating the ordinary workers as little more than personal servants. It’s better to say ‘most of the time’, because there were exceptions, though they were rare.

Proud men like Jiad Ali were outwardly respected but often hated by the bureaucrats because they couldn’t be easily coerced into acts of corruption. Jiad Ali was aware of this. He knew the government bureaucrats pretty well. But even he had to bow before the tremendous power of the higher-ups. He rued that he could never aspire to such a high position. His colonized mind was spellbound by their power, radiating solid confidence, like the red-brick walls of the government mansions. Though he couldn’t dream of entering the Indian Civil Services, he did manage to provide Alamgir with all the educational requirements to climb the ladder of the Bengal Civil Service.

Sati said, “I went to Calcutta with a scholarship, though my main goal was to learn Rabindra Sangeet.”

She stayed in Calcutta for two years, ’67 and '68. She had learnt music from a famous teacher. Initially, there was a problem with her lodging. Eventually, her status as a journalism student earned her a spot in a postgraduate hostel. But she faced a lot of harassment from the other students in the hostel for being a Muslim and was ousted from there within a month. Even the hostel superintendent, a professor, had tacitly supported the students. As the final act of humiliation, her hostel mates tossed her bedding and suitcase out on the road one day with some ridiculous excuse.

Sati had been barely three or four months in Calcutta at that time. She knew very few people. In a state of despair, following someone’s advice, she had come to College Street to seek help from Saroj’s group.

With some prodding, Saroj’s memory came alive. Saroj and his friends had actively protested to the hostel authorities, but it wasn’t feasible for Sati to stay there any longer. She found a place near Park Circus as a house guest with a Muslim family. At last, memory flooded Saroj’s mind, “Oh! That girl was you? How strange!”

Sati said, “Very few things in this world can surprise us anymore. Our experience of the last six months has taken care of that.”

Saroj said, “Sati, my name is Saroj. Saroj Ray. I don't care to be known as Manik anymore. Since you know this already, please keep it a secret for now.”

Jiad Ali had launched his son's career toward his desired goal. And Alamgir Mansur had sent his daughter to Calcutta to learn Rabindra Sangeet. The social evolution inherent in these two acts owes much to the Partition. The Independence of India, immediately followed by riots and the Partition, had created such tumultuous cultural and social changes, the likes of which were rarely seen in any other countries.

There was no equity of various classes within the two main religious groups in Bengal. It was a fact that the Hindus had occupied the higher classes for many years. Westward migration of a large number of the educated middle class caused havoc in the administration, education, and the cultural fields of the newly minted East Pakistan. Abu Hena’s father and forefathers had accumulated some money but had never acquired much education or culture. The culture of the Hindu middle class, with Tagore as its icon, started to attract the new Muslim classes. There was a need for educated people to fill many vacancies in schools, colleges, and government posts. Educated as well as undereducated Muslims who came from West Bengal initially found easy jobs, unlike the Hindus who migrated to India. In the future, this educated middle class would soon form the main political group, as there wasn’t much of a wealthy upper class left in the eastern part of the new country named Pakistan.

In the meantime, the gentle Tagore-infused cultural life was becoming the desired norm amongst the educated Bengalis of both faiths. Thus, educated Bengali Muslims were strongly attracted to it. There were hardly any Bengali leaders with appropriate life stories to inspire the masses. Nazrul’s life story was stimulating but also fearsome. So, Bengalis only accepted his songs. Women like Sati tried to satisfy their cultural urges with the stability and comfort of Tagore and Nazrul’s songs, along with incense and tuberoses. More modern women added poets such as Bishnu Dey, Jibanananda, and Sudhin Dutta. East Bengal’s own literary world saw the rise of figures like Al Mahmud and Shamsur Rahman, whose sharp intellect quickly won over even the most cynical critics.

In the meantime, people like Abu Hena hung on to their ancient trades in jute while consolidating their shrimp export and hotel management. The absence of cultured, gentle ‘Hindu maia (women)’ was quickly filled up by girls like Sati.

Perhaps that’s where the problems started. How could anything compare with the material comfort and bliss that money can buy? No other wealth has the audacity like money. Abu Hena and others had plenty of money, so when Sati started her tanpura practice in front of the flower-bedecked portraits of Tagore and Nazrul, Abu Hena’s mother could not tolerate it for long. One day, in her pure Mymensing accent, she exclaimed, “Oh my pampered daughter-in-law! She lights her lamps just to fart!” By that time, Abu Hena had given up trying to win his wife’s heart. The cultured lifestyle and speech remained stubbornly out of his reach. Unknowingly, he supported his mother, “Akz-zakly! What rubbish you sing. There is no sans in them!”

Sati’s life became difficult.

It was inevitable that Sati and Abu Hena’s warring lives would become further apart, one day forcing her to leave the country with Hena, Rumela, and Abdul Kuddus to this relief camp, where she would have to wait in queues for every item. The Red Cross had erected temporary latrines made with synthetic sheets in the field adjacent to the schoolhouse. As a multiplication sign creates four angles, four seats were made in each latrine block. Two dozen such blocks were lined up, plus a few were scattered around. There was hardly any privacy. The synthetic bolt disappeared within the first few days. Among the pile of excreta, life slogged on, mired in daily fighting, pleading, lies, pretenses, daring, jokes, and obscenities.

These hapless men and women lived their ghastly lives with their tears, boasts, curses, excreta, blood, pus, rotting, swelling corpses and abortuses, and putrefied humanity.

“Are you Manikbabu?”, or “Is your name Manik?” or “Have we met before?”--None of these were Sati’s questions. Her question was, “Aren’t you Manikbabu?”

Saroj again asked, “Would you like some tea?”

Sati said, “Perhaps another time, don’t worry. I have come today to ask for a big help.”

Sati was looking for accommodation for her family. Rental houses were scarce in this small town. Whatever was available was already snatched up right away by the early arrivals.

Still, Saroj felt the urgency to get her some form of shelter. And he promised her that he would try his best to get them out of the hell-hole of the refugee camp as soon as possible.

4.

Nobody in Majher Bondor knew him as Manik. He was hiding in this small town as Saroj Ray, the cousin of Doctor Manish Ray. Manish was an orthopedic, and as his ‘jobless, semi-educated brother,’ Saroj worked as his assistant. He applied plaster to the bandages, cut the plaster when needed, fixed the traction pulleys to patients' beds... that sort of work. It was ideal for hiding his identity. After a few days, Manish himself started calling him Saroj, even when they were alone. Doesn’t a name mean anything? Manish knew him as Manik from their childhood, yet he completely forgot the old name within a month. Even Saroj himself forgot his own name! That’s why he was so startled hearing his old name from Sati.

It was not just fundamentalism or a rejuvenated form of crude nationalism, but a blind urgency to return to the historic source of the revolution. Frequent peasant revolts during much of the British rule and later on the armed rebellions in Telengana and Kakdwip constantly inspired the nascent socialist parties. Whatever the leaders might have thought, the ordinary party members and the general public always dreamt of changing the old structure into an honest, strong, humane society. And that was the blueprint for the ultimate armed revolution for which thousands of workers were ready to throw themselves into the fire.

This whole thing was an unstoppable urge to return to the original socialist ideals of the nineteenth century. It wasn’t confined to the Naxal movement only, similar movements were seen in the sixties, almost all over, and not just in the third world. In Europe, the student movement in France in sixty-eight was an example.

Getting over the initial panicked stage after settling in Majher Bondor, Saroj realized he had had enough of passion and philosophizing about revolutions. Now was the time to think about all this calmly.

Nobody believed the revolution would be successful in the seventies, not even in the eighties or nineties. Everyone knew Charu Majumdar’s Freedom Decade was just an empty slogan, as proved by actual events. Even then, people believed in the impossible. That too was a type of faith—a faith that had tremendous political power. Long live revolution!

Many revolutionaries fell prey to such faith in the seventies. Even those deluded in the sixties built up another illusory dream, more mythical worlds. Thus arose illusory Muktifauj (Liberation Army), illusory Muktanchal (Liberated Land), illusory war, illusory capture of state power, even illusory prime minister and president building a parallel, alternate world. They would argue about it among themselves and write essays. Even give interviews in the newspapers.

During September-October 1970, scattered violence broke out in Calcutta and surrounding areas. A paramilitary group called E.F.R. set about squashing the Naxals. Within fifteen days, Saroj found out how unrealistic their demands were. Within fifteen days, he realized that he had no shelter, no safe haven, not even a trusted supporter or comrade with whom he could rest safely for just a few hours. Most glaringly, none of them had any alternative but to get stupidly beaten up. A few thousand did die just like that. There were no retreats, no treaties, no agreements for truce, no opportunity to use modern arms, no clearly identified enemy, and no well-defined tactics in this strange, terrifying warfare.

He had spent a night like that in Ranabir Gupta’s house in Sealdah. Ranabir was a colleague of Saroj’s younger brother, Pranab. The next evening, Ranabir brought Pranab. In those days, people connected to political movements couldn't even make any simple decisions--every decision had to be of historical importance. So, Saroj and Pranab, too, were stuck. Pranab had a job, and although he was loosely connected to the group, he had the responsibility of supporting his siblings and parents.

Fortunately for both of them, Ranabir had nothing to do with politics. Why he remained friends with party workers like them was not clear. But that’s how it was during that tumultuous period. Ranabir’s father had retired from the merchant office and was busy in the share market. He used up all his savings and became even busier after his retirement. One can’t deny that he understood stocks and shares very well and worked the market expertly with a fifteen-year-old cancer lodged in his throat. It was no wonder that his son would also manage money well. But it was a wonder that when Saroj couldn’t find anywhere to rest for even two hours, when he was at the risk of soaking the ground with blood and becoming a great martyr, Ranabir had called him in and sheltered him for three days.

Seeing Pranab, Saroj sighed and said in English, “Now what?” A Bengali would spout English even in moments of despair.

Pranab had the same question, too. He asked, “No hope from the party?”

“What party? I can’t contact anyone. Nobody seems to be around. I mean, there never was. The ones present are all in jail. There are no vacancies either. Perhaps at any moment I too would become a ‘never was’.”

The two talked back and forth but couldn’t reach a decision. Ranabir would light a cigarette and cough at the end of every puff. He took a long puff and asked, “What’s the problem?”

They didn’t take long to explain everything.

“Don’t you know anyone far away from Calcutta? Any friends? Relatives?”

Saroj remembered Manish. He was one of his close friends in college. He later became a doctor and moved north to a district town. Some people gathered fans and disciples while in schools and colleges. Saroj had some of those qualities. His good looks, sharp intellect, facility with words, and talent for writing poetry created a ring of fans around him. Manish was one of them, Saroj thought. Manish was very serious about his studies and perhaps had a crush on Saroj. As a last resort, a wish to seek shelter at his place was hidden in his mind for some time. During the heady days of the movement, he had pushed that desire away as mere opportunism, but now it appeared as the only reliable plan.

“There’s Manish in north Bengal, Manish!”

“That’s it! Pack up. For the time being, go ‘underground’. Don’t get into any trouble. Later, we’ll figure out according to how things evolve here.”

A couple of days later, Pranab and Ranabir handed him some money and saw him off at the Esplanade on a night bus to north Bengal. As they waved at him from the brightly lit roadside, Saroj suddenly felt meaningless and irrelevant. He realized clearly that he didn’t have the mental strength to hold on to a promise or remain motivated for long. Although his connection with Calcutta was limited to occasional visits over the past three years, he felt he was leaving the city forever. He had never before felt the separation so acutely.

Lights were turned off inside the bus as it plunged into the darkness outside the city. As it picked up speed, only the arc in front lit up by the headlights could be seen. Sitting idly inside a fast-moving machine, Saroj suddenly felt utterly empty and bankrupt, with nothing left for him to do. He wasn’t in control of anything anymore. Some undesired metamorphosis was happening within him, and he's unable to mount the slightest resistance against it. He shut his eyes and let himself blend with the speed and sound of the machine.

Many years ago, as if in a previous birth, he had gotten stuck in the rain with eight or ten cows. He had gone to the grazing field to herd the cows home. They were a bunch of useless cows; they didn’t give a drop of milk. Some were too old, some stopped producing milk due to lack of care, some perhaps due to other natural reasons. Still, they lived. If any of them gave birth to a calf, a quarter to half a ser of milk could be obtained for a few months. But they didn’t even have a person to milk the cows in those days. So, the cows remained unattended. By mere habit, someone would remember to herd them home in the evenings. Saroj wasn't yet ten. The herding chore fell on him and his brothers.

The pasture was far from their house, so it seemed to the eyes of a young boy. He was loitering aimlessly with the cows. Suddenly, the light of the Chaitra evening in that empty field turned an ominous pale. One cloud from the north-east corner grew huge, and the wind picked up. He and the cows took one look at the sky and started running towards home. Lightning streaked across the sky. The cows -- Dholi, Kunda, Chandi, Madhumangal…they knew him -- they bellowed as they ran, seemingly calling out to him to run faster. As the rain overtook them, they sought shelter under the shade of a chandi-mandap.

The pavilion was open on all sides with a high tin roof and an earthen floor. People who had made it for prayers and worship were long gone. Even their children and grandchildren had left home. Saroj led the cows in and stood in the middle near the empty platform where an idol might have stood in the past. It was hard to stay dry in such a forceful storm. The cows surrounded him. It was rapidly getting dark. There were large holes in the floor. A snake emerged from one of the holes, barely twelve or fourteen cubits away. Saroj spotted it only because of its movement, otherwise, it was too dark to see anything in the deepening shadows.

The snake raised its head and checked out the newcomers. Saroj knew the nocturnal snakes needed to be respected. Even in the gloaming dark, the round mark on its hood flashed. Saroj warned the farthest of the cows, ‘Dholi, don’t move!”

Dholi was young, less experienced.

All of them stood still and stared at the snake. Everyone was alert.

As the snake entered another hole in front, they all felt more insecure. Even the solid areas of the floor were riddled with tunnels underneath. Any step might collapse into a hole. And the snake might come out of any of the nearby holes. It had emerged to hunt its prey. What do you say Kunda? Wouldn’t it give us some space?

Dholi suddenly threw all four legs and jumped up. No, the snake didn’t bite her, but she was startled by a rat running away.

Along with Dholi, others too became restless. It was not wise to remain between the predator and its prey. Kunda moved a few steps outside, then turned her neck to look at others, meaning ‘come outside, the rain is harmless, but--’

They all followed Kunda out. Kunda jumped down and picked her tail up, signaling them all to run. They all ran towards the home in the rain and darkness.

He had just got in after shoving the cows in their shed. He was so drenched that water flowed around his feet as he stood on the veranda. When his mother came out to wipe him with a towel, he peered suspiciously at her face in the darkness. The light from the hurricane lamp inside fell obliquely on her face. He knew that the mother of a boy who went out in the rain to herd his cows would never care to wipe his face when he returned. She had no time for such things. Every year, she had to give birth to a baby, and in between, she had to cook for a large family. Did that mean the date and time were already decided?

As he looked at his mother, she looked away. Then, while drying his hair, she held his head close to her and sobbed. Now he understood. It would be tomorrow. Tomorrow he and his parents, brothers and sisters would have to leave this house, these trees and bushes, village, river, ponds, grandfather’s vacant lot, the ancient temple, that wonderful place where he swung from the roots of the banyan tree and jumped in the water, splashing wildly, the widespread open fields where he and his friends flew their kites and played football—they would be leaving all these for a place named Calcutta where people have rice for lunch and roti at night. Their village was emptying out rapidly. Surreptitiously, behind everyone’s back, families were leaving—the lawyers, doctors, teachers, then the washermen, barbers, the potters—who would they depend on? They too left late afternoon through the lengthening shadows, twelve of them, boarding the boat moored in the canal.

“Stay inside the cabin.” The elders directed.

We are not going anywhere; we were never here. Better to remember that.

He remembered then that he hadn’t seen his mother since last night. Nor did he see his aunt. Though his cousins were there with him. As the boat left the banks, his heart ached. Mother and aunt must have remained hidden in a secret room in the house. Their children were leaving them, who knew for what, who knew if in safety or danger.

As the boat moved, an invisible thread tying him to the village grew longer and longer. The pull became stronger as the thread grew. He had no idea then that he would have nobody to call his mother for the next fourteen years. This separation would be a significant event in his life and give rise to a loneliness he would never be able to shake off completely. It would torment him all his life with a prophetic pain, forcing him to accept all that would come his way.

- 1 | 2 | 3

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us