-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Translations | Memoir

Share -

A Scrapbook of Memories and Reflections: by Ketaki Kushari Dyson [Parabaas Translation] : Ketaki Kushari Dyson

A Scrapbook of Memories and Reflections Ketaki Kushari Dyson

Me wearing a Bishnupur sari that I bought from the person

who made it at his cottageThis section will, I think, be in the nature of a postscript. Maybe like topping up a tank. To arrive at Oxford from India in the autumn of 1960, as I did, was in many ways a very complex experience, much more complex, I suspect, than my fellow students around me would have realized. For a start, it was for me an intensely international experience. I had to undertake a long journey to arrive at my destination. First, I had to travel by train across the vast ‘subcontinental’ expanse of Central India to catch my boat. My father accompanied me on the long railway journey from Calcutta to Bombay. Traversing the distance between those two cities, the miles and miles of Central India lying quietly in the moonlight, was a learning curve in itself. In Bombay we had to stay in a hotel for a few days until my boat, the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company’s ss Canton, arrived from the Far East. And my father spent a good part of his energies in trying to persuade me that I must not try to avoid eating beef while at St Hilda’s College: if I did, it would be pretty difficult for me to survive. He assured me that I had his full permission to eat beef.

I am told that how they were treated as women was a big issue for female students at Oxford in the sixties. Well, it was and wasn’t. The devil, as always, lurks in the detail. When a girl was ‘sent down’ from my college for being found, one afternoon, in bed with a boy from a men’s college, we protested, but our agitations could not bring her back. In those days I also received a clear impression that getting engaged and being able to sport an engagement ring were cherished targets for many of the girls. Yes, I did sign a famous letter drafted by Judith Okely and Devra Wiseman that was published in a student magazine, claiming that sex before breakfast could be a good thing, but it was treated more as a hilarious issue than anything else. It gained us some ‘student-ish’ notoriety, but I really don’t recall any very vociferous and self-conscious feminism in my first three years at Oxford.

For me, as I recall, how the daily diet tasted, and the dramatic change in the cuisine to which I was being exposed on a daily basis, were key issues. How the food tasted in the college dining-room and how I could cope when the college kitchen closed over vacations became bigger issues for me than the issue of feminism and how I was being conned as a woman. The Oxford term was just eight weeks, and when the college kitchen closed, usually after nine weeks, the main meal of the day for someone like me, staying with a landlady, became a major issue. Landladies provided ‘bed and breakfast’. They did not provide lunch or dinner. One had to fend for oneself for those meals. ‘Bed and breakfast’ tenants did not have access to a landlady’s kitchen. So for a start one had to eat reasonably well at breakfast. I had two eggs every morning. One morning one of the eggs was badly addled. I couldn’t eat it. My landlady wouldn’t replace it. ‘I can’t give you three eggs in one morning, Ketina’, she commented. (She called me Ketina — somehow she couldn’t manage my first name.) While living on Iffley Road, I depended a great deal on Chinese restaurants in the Cowley Road area.

Mind you, the task of guarding oneself as a woman was important enough on the ship when I sailed for the first time. I shared my cabin with a pleasant Chinese girl who had come from the Far East. But there was a middle-aged Indian man on board whose attentions and comments I did not like. Another fellow traveller who, like me, was a state scholar from West Bengal, going to Britain to study a science subject, took on the task of guarding me from the unsolicited attentions of the middle-aged man.

The sea voyage was an exciting adventure. The waters were dazzling, and occasionally there were sea fish leaping. Aden, the Red Sea, the passage through the Suez Canal, with people cheering us from the African side of the transit, emerging out of the canal at Alexandria, where traders from below sent merchandise to the upper decks by means of ropes: these were memorable experiences indeed. When they saw my face, the traders would exclaim: ‘Nehru good, Nasser good!’ Of course, that was cheering. Going through the passage at Gibraltar was a unique experience. The seas were rough in the Bay of Biscay, and the ship, which was originally going to Tilbury landed us in Southampton. A Bengali student at Oxford who was the son of one of my Presidency College teachers, was there to greet me. He was going to meet me in Tilbury, but when the ship decided to drop all passengers off at Southampton he had been duly informed by the shipping company of the new situation. By means of a telegram, of course, which was the appropriate technology of the day. I had to go with him by train from there to London. I noted how the entire countryside looked more like a ‘cultivated garden’ than a sample of ‘wild nature’. In London I had to do some necessary business with my sponsors at the Indian High Commission’s education department. Only then could I finally board my train for Oxford, my final destination. I remember my tutor Miss Elliott coming to meet me with a smile, across puddles on the college grounds. A damp brisk breeze was blowing.

The fact that India had been a part of the British Empire until 1947 was a key factor in determining how that country and people originating from there were viewed in Britain. In those days Indians could not go to study in a British university straight from an Indian school. It was reckoned that their training in an Indian school would not be good enough, although of course it was the British themselves who had established and rolled out the modern-style educational network in their overseas territories. In Calcutta we did not have the sixth form and A-levels exams. I had been through the Intermediate Arts and B.A. Honours exams. In due course I would have sat for the M.A. exam, but I boarded the ship before that was due. In those days, Indian students who came to do a degree at Oxford had to have a B.A. or an M.A. degree already from their original country. This would be the second time they would hunker down to do a degree course. We were exempted from having to take the prelims exams, granted ‘senior status’, and allowed to finish the Oxford degree course in two years instead of three if we chose to do so. The ambivalence that hung over our status meant that only those who came to study on parental funding did their course in two years. Those who had any kind of access to public funding tended to spend the full three years pursuing the Oxford course, even if they already had a B.A. Honours or an M.A. degree from their country of origin. Caste consciousness is a very special phenomenon. And the Indians collaborated with the British in forging a special approach in this respect. The Oxford degree course was highly valued in India for equipping a person for a university teaching career. I had a state scholarship from the government of West Bengal and my sponsors were canny enough to realize that it was simply better for their students to spend the full three years in pursuing the Oxford course than to try to cram it into two years. My scholarship was for the full three years, so there would be no loop-holes through which a foreign student like me could be dragged down and punished for the perceived inferiority of her country of origin.

Hilariously, however, ‘as it may hap’ in life, sometimes it is possible to quietly open a side door through which one can establish one’s credentials without any hassle. For me Sanskrit proved to be such a door. I would not be taking ‘prelims’, so what would I be doing with myself in my free time in my first year? Miss Elliott decided that she would read some of Virgil’s pastoral poetry in the original Latin with me. That was a good experience. I could navigate by means of a facing translation. No problem there. My knowledge of Sanskrit was a great asset in unlocking the Latin texts. When we started Old English, Miss Sisam found my knowledge of Sanskrit very handy indeed. She often checked with me if this or that Old English word had a cognate word in Sanskrit. That was fun. For Miss Sisam, who taught us Old English and Middle English, my knowledge of Sanskrit became a real bonus. After all, Sanskrit was supposed to be the oldest surviving member of the Indo-European family of languages, and the formidable Panini was the first person who had codified the salient principles of Indo-European grammar. In due course, after I left Oxford, I translated some Old English (that is to say, Anglo-Saxon) poetry into alliterative Bengali half-lines. My first translations from Anglo-Saxon were published in Visvabharati Patrika, and later, with additional translations first published in the little magazine Heenayan, as a little book. And here comes a pertinent problem. It concerns cultural perceptions. Who cares about what you do (or think you achieve) in a foreign language of Asian origin, that is spoken by a mere … er, er, … well, a mere 200+ million people in the world? And that encapsulates a problem that can dog you year in, year out, even in a posh place like Oxford, or a supposed hub of cultural diversity like London.

Once I heard the formidable Seamus Heaney recite from his translation of Beowulf in London. I went up to him to say ‘Hallo’ and to tell him proudly that I too had translated a small section of that epic poem into alliterative Bengali half-lines. And indeed I had translated several Anglo-Saxon lyrics in this manner too and had published them all together in a little book titled Anglo-Saxon Kabita (or Anglo-Saxon Poems). Heaney looked at me in an incredulous manner, then commented that perhaps that task was easier for me because I was nearer to the ancient way of doing things. Translating Anglo-Saxon poetry makes him a brilliant translator, but in my case the same activity is a sign of my primitivism! So how does one work around such prejudice? The truth is that modern Bengali poetry is not written in oral-formulaic alliterative half-lines!!

The famous Dame Helen Gardner once told me that we modern women expected far too much. We wanted a career, and we also wanted a family. But it was not possible to have both. One had to choose. She, of course, had chosen the life of an unmarried university teacher. In my undergraduate years Oxford colleges were single-sex institutions and women’s colleges were dominated by teachers who were spinsters. I am not making any specific comments on Cambridge as after all these years I am not too sure about the exact details of the situation that prevailed over there, but my overall recollection is that the situation there was pretty similar.

There was certainly a great deal of rumbling about discrimination from the late sixties onwards when I was a graduate student. At one point a commission of inquiry was set up, to investigate discrimination in academic hiring. What were people complaining about? We were asked to send in all relevant information on recent applications: the nature of the jobs, what was required, and our qualifications. I sent in the details of about 30 of my job applications. I hadn’t had a single interview. The discrimination was actually four-fold. I was not wanted because a) I was a woman, b) I was a married woman, c) I was a married woman with two small children, and d) I was a person of Indian ethnic origin. How does one fight discrimination on such multiple grounds? The commission did reply, saying that there was no doubt that I was being discriminated against on multiple grounds. But the only way to fight such a battle would be to start a campaign in The Guardian. I didn’t feel that I had the stamina or the diplomatic skill to do that. In those days I couldn’t even get that paper to publish a matter-of-fact ‘Letter to the Editor’ from me. How could I get them to support me through a long campaign? At that point I went to teach at a provincial university in West Bengal for a year, taking the children with me. They went to a St Xavier’s school, where they could be taught in the medium of English, and where they finally acquired the basic skills of literacy and numeracy. While I was there, I published my first collection of poetry. In Bengali, of course. An editor suggested that I try writing a novel. I didn’t think I was capable of writing a novel, but once I was back in Kidlington, I decided to accept the challenge. The elm-trees were dying of what came to be known as the ‘elm-tree disease’. Sitting by the back bedroom window, watching the dead and dying elms, I decided that I would have a go at writing a novel. No harm in trying, was there? — so I told myself. I drafted it, sitting by the ironing board, in long hand and on the large, slightly joined computer paper sheets in use in those days. I later typed it up on a manually operated Remington Bengali typewriter which the SOAS (The School of Asian and African Studies attached to the University of London) was throwing out for £10. Of course, I later graduated to computer-operated typing even in Bengali. The novel that came into being at the ironing board was Noton Noton Pairaguli, first serialized in Desh and then published as a book by Ananda Publishers. It was widely read, including in the Bengali diaspora. It won me many new readers. It has since then been re-published by another publisher and given a new lease of life. Early on in my life as a wife and mother I decided to become a freelance writer instead of chasing academic jobs.

Of course, there are those sceptics who hold the view that there can be no such identity as that of a serious bilingual writer. They say you cannot be deemed a proper writer until you have written a novel in English. According to them, being a bilingual creator in poetry and scholarly books is not enough. To show your mettle as a writer you must produce English-language fiction; nothing else will do. So discrimination is a many-headed monster, as in mythological narratives. You may cut off one of its heads, but another one will grow in its place. It is really a strategy for the consolidation of power. When my husband and I came back to England from Canada so that I could do a doctorate at Oxford, Miss Elliott exclaimed: ‘O Ketaki, why have you come back? There are no jobs in this country!’ When I started applying for jobs after completing my doctorate, she apparently did write a reference for me when I applied for a job at Dundee, but when she found that I had not received any call for an interview, she seemed to lose interest in backing me. On one occasion when I applied for some kind of post-doctoral fellowship at St Hilda’s itself, she candidly said that even if I applied, she would not back me, as the college wanted to hire someone who was the wife of an Oxford don. How can one fight such a deep-rooted system of discrimination? The college’s Old Girls’ network gave me a small grant for one of my poetry translation projects, but when the relevant book came out from Oxford University Press, Delhi, the college did not ask me to do any event to publicize the work — they did not want to have any further association with it. These happened to be poems by the great Bengali poet of the 20th century, Buddhadeva Bose. Some of these translations have since then been re-translated into Finnish by the eminent Finnish translator Hannele Pohjanmies. If I hadn’t translated some of these poems into English in the first place, this project of re-translation couldn’t have taken off.

Those who have some idea of my bio-data know that I have done some important work on Rabindranath Tagore. I have written four books that concern him, two of which are in English, and in addition I have written many articles and papers on him in English. I am known for my work on Tagore and Victoria Ocampo from Latin America to China, but why should I have to beat my own drum about it, shouting ‘Look at me! Praise me!’ That does not appeal to me. I do not have to do that for my audience in India. They do what they can for me, without pestering me about it, even when they realize that I have been a British citizen since my marriage. Among European countries Germany is very grown-up about it. The German Academic Exchange (DAAD) helped me for a major Tagore research project even when they realized that the huge book that would come out of it would be in Bengali. Every important book that gets written in today’s world cannot possibly be written in English, surely! Come on, folks, grow up, you have to discard some outdated imperialistic illusions! And please understand that the formation and elaboration of one’s identity are continuously evolving processes. Important strands of my literary life can be viewed by anybody on my website.

As I have already indicated, it is difficult for me now, because of my dimming eyesight, to narrate events from the past in a proper chronological sequence. It is now a fight against the rolling forward of time and the dimming of my vision.

I have already mentioned my parents-in-law. They always welcomed me as a new member of their family. So did Robert’s elder brother Roy and his wife Dorothy. Roy and Dorothy are both dead now. Their children are adults now and have their own families. I must admit that I have not graduated to the use of Facebook to interact with the younger members of the extended family!

Let me include a few memories from our Canadian days in this section. We crossed the Atlantic by plane and arrived at Montreal, where we were given gracious hospitality by our friend Jon Wisenthal’s parents. This was the year of Canada’s ‘centenary’ as a self-governing confederation. People took great pride in that. Jon’s mother helped us with our sightseeing and we certainly saw ‘Expo 67’ which marked that centenary. We then crossed the continent by train, changing trains in the middle of the night at Winnipeg. It was the so-called ‘northern route’, and there was snow on the ground though it was springtime approaching summer.

Robert and I had begun our married life in one room in Brighton, so we were keen to live somewhere where we could have more space. We were advised that the best and quickest way to achieve this in Vancouver would be to just go ahead and buy a house on mortgage; we could always sell it if we decided to leave the country — house prices were rising and we would not make a loss. Which is what we did. As it turned out, we were in Canada for not quite two years. But our first child was born there, and we do have some very fond memories of our life in our first house, the first house that was formally owned by us.

Me with Virgil in the front garden at 4623 West 12th Ave Vancouver

It was a bungalow with a substantial basement. Robert fitted out a part of the basement area as a separate room with bookshelves so that it could be used as a study. The remaining space was dedicated to the deadly serious business of doing our laundry. Canada taught us how handy double sinks could be, both in the kitchen for washing our dishes and in the bathroom or any other available space for washing our clothes. A lesson was learnt for a lifetime.

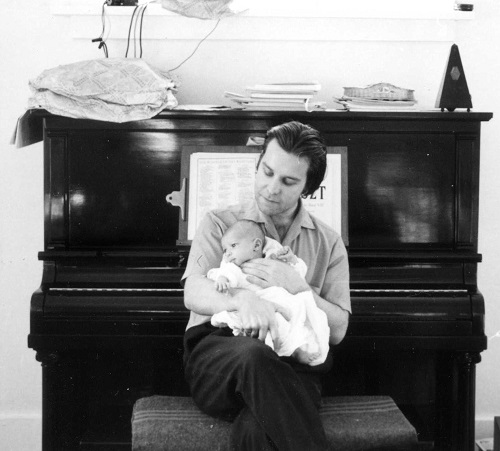

Robert sitting at his Heinzman piano in Vancouver with son Virgil

When I first came to England in the sixties people tended not to rinse their dishes after washing them. A solution of detergent and very hot water would be made, in which cups, glasses, plates, and cutlery would be washed and then allowed to drain on the draining board for a minute or two. They would then be wiped dry with a cloth. I suppose the regime was slightly different for big dirty saucepans, but for most crockery and cutlery people tended to skip the rinsing process and rely on a vigorous rubbing with a tea-towel. It was the use of synthetic detergents that made this regime possible: soap would have remained slippery for much longer. What synthetic detergents did they use? When living with landladies one had no access to their kitchens, so I don’t know what they did, but when living in St Gregory’s House at Canterbury Road, Oxford, we had the advantage of a single but large sink, so things could be washed in a plastic bowl and rinsed under the tap away from the bowl’s edge. Living in one room in Brighton, with a tiny gas cooker and one sink, we had to adopt many strategies for washing and rinsing dishes, while clothes were washed in the launderette. Canada finally showed us that much of the hassle could be avoided, both in washing clothes and in washing dishes, by means of that great asset, the double sink!

In this scrapbook of recollections I cannot but remember with great affection the very first house we owned, our house in Vancouver. Excellent natural wood was available in British Columbia, so Robert, who has always been good at woodwork and carpentry, was in his element there. Our L-shaped kitchen-diner offered him the opportunity to do something neat in the restricted dining space. He made a table and two benches which made the most of that space. When we left Canada, he dismantled them and they became pieces of wood which could be packed flat. We brought them back to England, where they were re-assembled as a table and two benches. We have used them ever since!

The front of the bungalow at Vancouver had an apricot tree against the front porch and we could pluck the fruits straight from the branches and eat them. For me that was a special treat! Sadly, we heard later that the next owners of the house had cut down the apricot tree that used to grow against the front porch.

Me with Virgil at our front door at 4623

From our bedroom window on a fine day we could see the Rocky Mountains against the sky. I loved the view. And for Robert the pride that ordinary working-class Canadians took in their jobs was exemplary. He was struck by the way a man from the refuse collection department, who was to remove some rubbish we cleared from the house, came to the door, rang the bell, and introduced himself and gave a lecture on how we should have placed it for collection. And I remember the absolutely brilliant nappy laundering service that was prevalent in Vancouver at that time — at least in the area where we lived. Used baby-nappies were collected at the front door and returned — washed, dried, and sterilized — the next day. Even if you had a fully automatic washing machine, this was a real bonus for new mothers. You could do all your other laundry in the machine and not worry about your baby’s nappies, which would be collected and returned dry and sterile on a daily basis.

In Vancouver we were blessed with good neighbours. On our right-hand side if we faced the street lived Dan and Diane Bowers with their four children. They were very much into outdoor activities such as camping and we did once visit their cabin in the woods. The Bowers couple took us in their charge much as a dada and bowdi (an elder brother and his wife) do in Bengali society. For instance, they quickly took note of the fact that we were not cutting the grass and concluded that we must not have a lawn mower. That was true. The overwhelming truth was that we were coping with our first child in a country where neither of us had relatives. We just had each other. One afternoon we heard Mr Bowers cutting our grass! We eventually bought a hand mower. And even I acquired the art of mowing the lawn with it.

Our Vancouver neighbour Diane Bowers with our elder son Virgil

There was of course space in the back for growing vegetables. I fancied growing parsley there and either I myself or Robert sowed some parsley seeds there. We ended up growing what can only be described as a forest of parsley. We have never grown such sturdy parsley in our subsequent life in England. They must have been seeds special to British Columbia.

Our parsley forest in the back garden at 4623

On our left side, facing the street, were a young couple with a son called Mark. Every afternoon over the summer months Mark moaned and protested against the ignominy of being put to bed while there was still light in the sky. His mother, who was an artist and had shoulder-length straw-coloured hair, ignored his moans and went through the ritual of coffee on the lawn. I have mentioned Mark’s persistent moaning in one of my Bengali poems.

Sadly, Dan Bowers did not live long. As I recall, we received a note from Diane simply saying ‘Dan is no longer with us’. We do not know how he died.

I wanted to include in this section some of those photographs from our days in Canada and this snap of our young sons in our Kidlington home, where Robert and I still live.

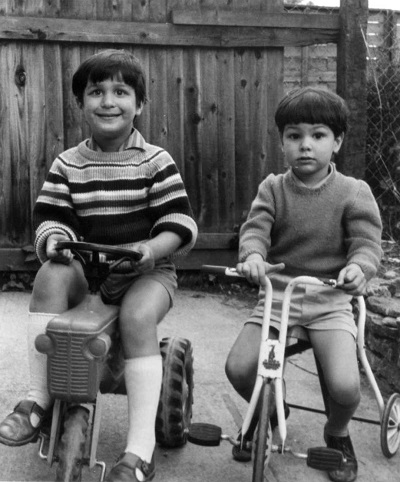

Our sons Virgil & Igor, in our Kidlington garden on their vehicles

In the end we came back from Canada in a bit of a hurry, as I was pregnant with my second child and hoping to start my D. Phil. researches at Oxford in the following academic year.

I had hoped that I would be able to end this concluding section of my recollections and reflections on a note of optimism, but fate is determined to thwart my plans. We now seem to live in a world where even those who call themselves Buddhists can persecute people of another faith. The environment proceeds from one crisis to the next pretty relentlessly, and ‘us urban foxes’ seem unable to do much to halt that chain of events. The ocean floors get cluttered with plastic bags and coral reefs are devastated. Maniacs shoot at people enjoying themselves at a concert. We seem unable to prevent the slide down the slippery slope.

Currently many Catalonians and mainstream Spaniards seem to be having problems with meaningful mutual communication. I hope they will be able to get over it. We have to unite against our common enemies, such as religious terrorism and the destruction of the environment we share. We need solidarity, not a perpetual fracturing of our common humanity. We need to be canny foxes to survive in the current world. How can we comprehend the shooting, by religious terrorists, of hundreds of worshippers in a shia mosque in Sinai?

On the whole, India tends not to put too much emphasis on what she can legitimately claim as her major innovations. The system of counting by means of nine numerals and a zero was developed in India. Arab traders brought it to Europe, where it was adopted. Some historians have wryly commented that it was a good thing that Europeans adopted the Indian decimal system of counting; if they had stuck to the Roman method of writing numbers, their science would not have made progress. Yet Europe has persisted in talking about Arabic numerals, when these should really be called Indian numerals.

Likewise, in the field of textile design, the motif of the tear-drop, taken over from Kashmir shawls, became a standard pattern in British textiles but given the name of the ‘Paisley pattern’ to commemorate the Scottish town where machine weaving was established during the Industrial Revolution. Isn’t it time to remember that the pattern really originated in the subcontinent? It is a major motif in Indian textiles, in shawls, scarves, stoles, saris, and all manner of printed cottons and silks from which shirts, dresses, kamizes or kaftans are made. Indeed, it is an ubiquitous motif, and crops up on everything from ties and blouse-pieces to curtains, table-cloths and bed-covers.

Detail of the Bishnupur sari tear-drop

Tear-drops on one of my shawls

Elaborate tear-drops (fractal-like) on my Kashmiri shawl

bought in the 1950s from a seller who came to

our door in Hungerford StI want to end this section with my long poem in English remembering Manipur, where I went for a conference earlier this century. Though Manipur is in the Indian subcontinent, my visit there is one of my more ‘exotic’ memories. I hope the poem will tell an interesting tale. This will be the final link in this chain of memories. Well, so be it. The urban fox in me does not mind as long as her memories are shared by a wider audience than before.

- Cover | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 (Last): Manipur Memories

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us