-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Rabindranath Tagore | Story

Share -

F is for Fail (original Bengali "Fail") : Rabindranath Tagore

translated from Bengali to English by Sreejata Guha

The head and the tail, or better still – Rahu and Ketu – how would it look if they turned away from each other sulkily? That was precisely the case here. The ancient Haldar family had split in to two, raised a brick wall along the centre of the gigantic mansion and the two halves sat with their backs to one another; one refused to set eyes upon the other.

Nabagopal’s son Nalin and Nanigopal’s son Nanda were of the same lineage, of similar age, attending the same school and of the same opinion where their age-old family feud was concerned.

Nalin’s father – Nabagopal – was of a strict disposition. He kept his son on his toes with studies and more studies. Under the weight of the school books were crushed his son’s every craving for spontaneous play, for junk food and for stylish clothes.

Nanda’s father – Nanigopal – was the lenient one. Nanda’s mother dressed him with care and sent him off to school, along with a handsome pocket money of three annas. Hence Nanda had the luxury of indulging in some ice candy, some roasted nuts, spinning tops and coloured marbles etc. which he consumed and shared equally and gained considerable popularity in his peer group.

Admitting defeat without a word, Nalin always thought, ‘If only Nanda’s father was my father and vice versa, then I would have seen who is better!’

But before such an event could come to pass, Nanda began to win prizes every year. Nalin came home empty handed, complaining of unfair biases and partiality from the school authorities. His father changed his school, hired tutors at home and even took an hour off his night’s sleep and added it to his study time – but the result was the same as ever. Nanda passed every year and soon cleared his BA exams. Nalin failed again and again, and remained stuck in the mousetrap of the Entrance class, or the final year in school, indeterminately.

At such a time his father took pity on him – the man died. After three years of valiant struggle, he was freed from the deadly vise of the Entrance class and a sovereign Nalin now flashed his sparkling ring, his gold buttons, his costly watch and strutted about trying his best to vanquish the fading glory of a lackluster Nanda. The carriage-buggy of the Entrance-failed raced past the horse-drawn ekka of the BA-passed effortlessly and the University degrees paled beside the Wellar horses.

Meanwhile the hunt was on for good matches for both Nalin and Nanda. Nalin vowed that he would marry a girl who was beyond compare. Nanda must be made to admit defeat before his carriage and his bride!

The one who sets his cap on the best, must let go of many other bests along the way. Nalin could not bring himself to accept any of the matches close to home, lest an even better one eluded his grasp and fell to someone else’s lot!

Eventually he got word that a Bengali gentleman in Rawalpindi had a tremendously beautiful daughter. A pretty face in the distance looks far prettier than the one close at hand. Nalin was very enthusiastic about this match. The girl was brought to Kolkata, all expenses paid. She was truly a beauty. Nalin said, ‘Whatever anyone may try, he would be hard pressed to outstrip Rawalpindi at the drop of a hat. At least no one would have the gall to say, “Oh, we had seen this girl once, but rejected her since she did not match up to our standards.”’

The word was given and the match was fixed. The trousseau was being put together, when suddenly one day a stream of maids and servants were seen leaving Nanigopal’s home with decorous plates full of a variety of trousseau on their heads.

Nalin said, ‘Go and have a look, what are they up to?’

He was told that it was the trousseau meant for Nanda’s intended bride.

Instantly Nalin stopped puffing on the hubble bubble and sat up straight, ‘This I must look in to.’

The very next minute the carriage pulled up at the gate and raced away carrying the spies and messengers. Bipin Hazra came back with the news: ‘She is from Kolkata, but she is a gem all right.’

Nalin’s face fell, ‘What are you saying!’

But Hazra simply repeated, ‘Gem of a girl.’

Nalin said, ‘This I must see for myself.’

His messenger said, ‘That is easy,’ and he rubbed his index finger and thumb together to show the jingle of a coin.

Nalin made the arrangements and saw the girl. The more he pondered over the fact that this girl was Nanda’s bride, the more his belief strengthened that she was more attractive than the girl from Rawalpindi. In the throes of quandary, Nalin asked his staff, ‘What do you think?’

Hazra said, ‘Well, we feel she is quite a beauty.’

Nalin asked, ‘Is she prettier or is that one prettier?’

Hazra said, ‘This one.’

At this Nalin began to perceive that this girl’s eyelashes were a shade thicker than that girl’s, her complexion was a tad rosier than the other girl’s with a hint of gold in the yellowish tinge to it. It would be foolhardy indeed to let this one get away.

Nalin lay on his back, puffing on his hookah despondently as he said, ‘Hey there Hazra, what do you think we can do?’

Hazra replied, ‘Your Highness, that is easy,’ and once again he rubbed his index finger and thumb together to show the jingle of a coin.

Needless to say, when the coins began to jingle for real, the desired effect was not hard to achieve. The bride’s father picked a quarrel with the groom’s father for no apparent reason. The groom’s father declared, ‘If I ever let my son marry your daughter then –’ and so and so forth. The bride’s father went one notch higher and said, ‘And if I ever let my daughter wed your son, then –’ and so on and so forth.

Thereafter, without further ado, Nalin raced past Nanda and rushed in to marriage with great pomp and ceremony at the appointed hour. He laughed as he exclaimed to Hazra, ‘Well well, this is called passing with distinction, eh Hazra? MA is for marriage, right? This time our babu of the other house has failed for sure.’

In a matter of few weeks, Nanigopal’s house also resounded with the sound of shehnai and kettle drums. It was Nanda’s wedding day.

Nalin said, ‘Hey there Hazra, go and have a look – who is the bride?’

Hazra came back bearing the news: the bride was the girl from Rawalpindi.

The Rawalpindi girl! Hah hah hah! Nalin laughed himself to bits. The babu of the other house could find no one else to wed – he had to pick the one we had rejected. Hazra joined in the laughter gleefully.

But as time passed, Nalin’s laughter grew weaker and weaker. His cheer was afflicted by a virus. A tiny germ of doubt whispered in his ears shrilly, ‘Oh dear, this one got away – and finally she fell to Nalin’s lot!’ The tiny germ of doubt gradually swelled in size like a bloodsucking leech and its voice grew heavier and louder. It said, ‘Now there is no way for you to get her, but in reality she was the prettier one! You have been duped.’

When Nalin went indoors for his meal, each and every tiny flaw of his wife’s nature glared at him and jeered at him. He began to feel that his wife had played a cruel trick on him.

When he had been engaged to the girl from Rawalpindi, he had received a photograph of her. Now he took it out and gazed at it, ‘Heaven’s above, what a fetching beauty. And I rejected this goddess, what an idiot I am.’

That night the groom left for his wedding reception in a magnificent carriage, with lights galore and bands of musicians. Nalin lolled in bed, trying to extract a modicum of consolation from his hubble bubble when Hazra arrived there – full of cheer, laughing gleefully and getting ready to poke some fun at Nanda.

Nalin hollered, ‘Watchman!’

Hazra recoiled fearfully and summoned the watchman.

Nalin pointed at Hazra and said in his broken Hindi, ‘Obhi isko kaan pokorkay bahar nikal do! Grab this man by the ears and throw him out this very minute!’

Ashwin. BE 1307Published in Parabaas, November, 2010.

The original story Fail was first published in Bharati, and later collected in Galpaguchchha.

Translated by Sreejata Guha.

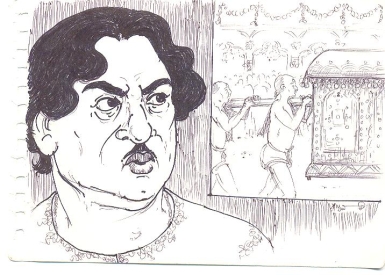

Illustration by Rahul Majumdar. An author and illustrator, Rahul Majumdar has several books to his credit.

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us