-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Satyajit Ray | Essay

Share -

Our Ray of the 70's and 80's : Somjit Dutt

We who grew from childhood to youth and young adulthood in the city of Calcutta

during the course of the 70's and 80's of the 20th century had the rare opportunity

to refer to one of the Titans of the screen, Satyajit Ray, as almost one of us : he was very

much our Ray. By the word our we of course never signified any equality of creativity

with him; for, we were then merely children or adolescents. We merely felt proud

in believing that he belonged to us, and was not, like other great Bengalis of the bygone

years a remote figure, Olympian in its isolation. At any given point of time during the

day, Ray could be counted upon to be seated at his study in his spacious and

old-fashioned apartment on Bishop Lefroy Road, writing a script or story, casting

roles, sketching scenarios, or musing abstractedly, his pipe held at a pensive angle by his

third molar.

We who grew from childhood to youth and young adulthood in the city of Calcutta

during the course of the 70's and 80's of the 20th century had the rare opportunity

to refer to one of the Titans of the screen, Satyajit Ray, as almost one of us : he was very

much our Ray. By the word our we of course never signified any equality of creativity

with him; for, we were then merely children or adolescents. We merely felt proud

in believing that he belonged to us, and was not, like other great Bengalis of the bygone

years a remote figure, Olympian in its isolation. At any given point of time during the

day, Ray could be counted upon to be seated at his study in his spacious and

old-fashioned apartment on Bishop Lefroy Road, writing a script or story, casting

roles, sketching scenarios, or musing abstractedly, his pipe held at a pensive angle by his

third molar.

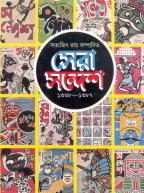

When I was a child, I became conscious of this man not through his films primarily but through his stories and the monthly magazine Sandesh of which he was one of the editors. Very early in their lives, almost all Bengali children of our generation came in contact with Sukumar Ray's book of nonsense rhymes Aabol Taabol; he was truly the Edward Lear of Bengal. Sukumar's father Upendra Kishore Ray Chaudhuri had bestowed on us his immortal fairy tale duo Goopy Gyne the minstrel and Bagha Byne the drummer. Our early childhood was touched by the magic wand of the literary creations of all three men, though Satyajit's detective novels and stories of science fiction began to appeal to us only a few years later. Sandesh was the vehicle through which the writers of the Ray clan reached our callow minds and created for us a world to live and delight in, removed as it was from the wordly world of school, homework and parental control.

Professor Shonku, the septuagenarian Bengali scientist, profusely bearded, and

bespectacled, strode into our imagination and created there a niche for himself. Ray

created the character in the 60's and by the middle of the 70's, it had secured a devoted

clientele amongst the children and adolescents of our generation.

Professor Shonku, the septuagenarian Bengali scientist, profusely bearded, and

bespectacled, strode into our imagination and created there a niche for himself. Ray

created the character in the 60's and by the middle of the 70's, it had secured a devoted

clientele amongst the children and adolescents of our generation.

But it was Ray's own Holmes - Pradosh C. Mitter, Private Investigator - popularly

known as Felu-da, that had a more powerful appeal to us, for he came to life, as it

were, in Ray's film Sonar Kella released in 1975. Felu-da, along with his trusted

lieutenant Topshe, and their credulous and perennially good-humoured friend

Lalmohan Ganguly, a writer of bizzare mystery novels of immense popularity and

proportionately low intellectual content, unravels a criminal case amidst the pituresque

Rajput fortresses nestled amidst the desert expanses of Rajasthan. The film was a

revelation to our young minds and it so happened that the child artist who played the

role of a boy with memories of an earlier birth in the film was a student of Patha

Bhavan, the school to which I

went; in fact, he was a classmate of my elder brother and I

But it was Ray's own Holmes - Pradosh C. Mitter, Private Investigator - popularly

known as Felu-da, that had a more powerful appeal to us, for he came to life, as it

were, in Ray's film Sonar Kella released in 1975. Felu-da, along with his trusted

lieutenant Topshe, and their credulous and perennially good-humoured friend

Lalmohan Ganguly, a writer of bizzare mystery novels of immense popularity and

proportionately low intellectual content, unravels a criminal case amidst the pituresque

Rajput fortresses nestled amidst the desert expanses of Rajasthan. The film was a

revelation to our young minds and it so happened that the child artist who played the

role of a boy with memories of an earlier birth in the film was a student of Patha

Bhavan, the school to which I

went; in fact, he was a classmate of my elder brother and I

later came to know him socially. Ray's son Sandip had also matriculated from Patha Bhavan, and its authorities were well known to Ray. Whenever Ray needed child artistes for his movies from the mid-70's onwards, he contacted some young teachers of our school with a view to recruiting a photogenic face with an intelligent mind behind it.

Meanwhile however, a re-run of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne had conquered our hearts, once and for all. In 1969 the film had been released and had run to packed houses; if my memory serves me, it ran for a record fifty one weeks -- almost a year -- and was by far the most commercially successful movie that Ray ever made. It was probably around 1973 that I watched this film for the first time. The film version was an elaboration of Upendra Kishore's original fairy tale and many features were added to it in the production, making it a sort of a world of its own, as real in our nimble imagination as that of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry or Jeeves and Wooster was for us later to be.

Few characters in Ray's oeuvre have been so compellingly portrayed as

those of the disarmingly foolish minstrel Goopy and the far more intelligent and witty

friend, philosopher, guide and accompanist on the drum -- Bagha. Tapen Chatterjee, then

a greenhorn actor, played admirably the role of Goopy and the inimitable Rabi

Ghosh, by the end of the 60's an experienced performer, was Bagha -- a role which

Providence seems to have reserved for him and him alone -- one which in its portrayal

has become legendary in the history of Bengali cinema. All this has gone into Bengali

folklore and delightful it was for us to to see before our very eyes the creation and

evolution of this musical world inhabited by boon-giving ghosts, kings warlike or

peace-loving, crafty

ministers, soldiers, magicians, generals, courtiers, princesses, horses, tigers et. al. -- all tied

into a whole by the bewitching storyline and the immortal music which was hummed

by one and all who watched the film.

Few characters in Ray's oeuvre have been so compellingly portrayed as

those of the disarmingly foolish minstrel Goopy and the far more intelligent and witty

friend, philosopher, guide and accompanist on the drum -- Bagha. Tapen Chatterjee, then

a greenhorn actor, played admirably the role of Goopy and the inimitable Rabi

Ghosh, by the end of the 60's an experienced performer, was Bagha -- a role which

Providence seems to have reserved for him and him alone -- one which in its portrayal

has become legendary in the history of Bengali cinema. All this has gone into Bengali

folklore and delightful it was for us to to see before our very eyes the creation and

evolution of this musical world inhabited by boon-giving ghosts, kings warlike or

peace-loving, crafty

ministers, soldiers, magicians, generals, courtiers, princesses, horses, tigers et. al. -- all tied

into a whole by the bewitching storyline and the immortal music which was hummed

by one and all who watched the film.

Alongside directing these movies, Ray kept producing a raft of stories and novels

that were published first in Sandesh and other frontline magazines such as Desh and

Anandamela and thereafter as books. We waited eagerly for every one of these and I

later came to know that anything which his young readers found less satisfying than

usual provoked them to deluge Ray with angry letters, to some of which the busy film

director patiently replied, mollifying the fury of young and innocent hearts with

promises of future thrills, which rarely failed to come. It was in the mid-70's that I first had the

opportunity to see the man in the flesh : it was, if my memory serves me, a

prize-distribution ceremony and Ray was the honoured guest; it was held in the

residence of his cousin Nalini Das, who was one of the editors of Sandesh and the

sister-in-law of the poet Jibanaananda Das. I was amazed by the remarkable physique

of Ray and did not fail to notice his keen, incisive eyes, which always appeared to have a

slight squint. And of course, his stentorian voice reverberated in our ears even after we

had left his presence.

Alongside directing these movies, Ray kept producing a raft of stories and novels

that were published first in Sandesh and other frontline magazines such as Desh and

Anandamela and thereafter as books. We waited eagerly for every one of these and I

later came to know that anything which his young readers found less satisfying than

usual provoked them to deluge Ray with angry letters, to some of which the busy film

director patiently replied, mollifying the fury of young and innocent hearts with

promises of future thrills, which rarely failed to come. It was in the mid-70's that I first had the

opportunity to see the man in the flesh : it was, if my memory serves me, a

prize-distribution ceremony and Ray was the honoured guest; it was held in the

residence of his cousin Nalini Das, who was one of the editors of Sandesh and the

sister-in-law of the poet Jibanaananda Das. I was amazed by the remarkable physique

of Ray and did not fail to notice his keen, incisive eyes, which always appeared to have a

slight squint. And of course, his stentorian voice reverberated in our ears even after we

had left his presence.

From then onwards, his impressive physical appearance became a sort of icon, a symbol of Bengali cultural imperialism. Bengal, of course, had never commanded a vast political empire like Britain, but in the cultural sphere her superiority over other regions of the Indian sub-continent was firmly established ever since Bankim Chandra Chatterjee emerged as a stalwart of literature, and Ray was to us a figure in which that noble tradition continued into the last decades of the 20th century; in fact, many have hailed him as very much a Renaissance man. He was in his fifties and sixties in the two decades that I discuss here, and physically he was perhaps no less impressive than the aging and wayfaring Tagore at the height of his powers. And whenever his booming voice was on the air, radio or television, ears turned from miscellaneous noises and the common din and became focused on his words with rapt attention.

In the last half of the 70's he followed Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne with its sequel Hirak Rajar Deshe, Sonar Kella with Joy Baba Felunath; throughout his life Ray had been interested in children and teenagers and perhaps no other major filmmaker of India has devoted so much time and effort to making movies targeted at a young audience. We were all very excited with both of these films and Hirak Rajar Deshe was visually more attractive than its predecessor because the latter was not in Eastmancolour (except the last scene).

Ray made his first feature film in Hindi Shatranj Ke Khilari in the late 70's and I

remember that I was a little disappointed with the denouement, for I had expected that

there would be a war; I was not yet 10 and the delicately nuanced ending went over my

head. Many years later, watching the film on television I was able to appreciate its

message and especially the memorable performances of Amjad Khan, Sanjeev Kumar, Shabana Azmi, Saeed Jaffrey and Sir Richard Attenborough.

Ray made his first feature film in Hindi Shatranj Ke Khilari in the late 70's and I

remember that I was a little disappointed with the denouement, for I had expected that

there would be a war; I was not yet 10 and the delicately nuanced ending went over my

head. Many years later, watching the film on television I was able to appreciate its

message and especially the memorable performances of Amjad Khan, Sanjeev Kumar, Shabana Azmi, Saeed Jaffrey and Sir Richard Attenborough.

The 80's rolled in with Ray's son Sandeep making a film on the novel Phatikchand which Ray had published a few years previously. The film was enjoyable and I still remember how greatly impressed we had all been by the performance of Kamu Mukherjee in the role of Harun-al-Rashid the juggler; Biplab Chatterjee's performance in the role of the criminal who kidnapped Phatikchand was very polished and skilful and I overnight became something of a fan of his after watching the film.

I cannot resist here the temptation to recall an interesting detail : the distributors of Phatikchand had not clearly stated in the advertisements that the senior Ray's short film Piku would be shown before the interval. A hall full of parents, with their children seated beside them, were somewhat disturbed to find that their children were exposed to the decidedly adult theme of Piku without their being able to do anything about it. I can recall vividly how my father, disconcerted, discussed with a stranger seated beside him (doubtless a father, too) in discreet whispers, how unadvisable and unjustifiable it was on the part of the distributors to show such a film before a children's movie. I always suspected, but never knew for sure, that the whole thing was a mischievous prank pulled off by the distributors, perhaps not without Ray's consent.

Piku and Sadgati were the films with which Ray began his journey into what turned out later to be the last complete decade of his life.

Sadgati was a deeply moving

film and the powerful array of performers consisting of Om Puri, Smita Patil and

Mohan Agashe lent an additional dimension to the strong storyline and since it was in

Hindi, reached an India-wide audience directly, as Shatranj Ke Khilari had a few years

ago, as opposed to his masterpieces in Bengali, which could only reach

non-Bengalis through sub-titles.

Sadgati was a deeply moving

film and the powerful array of performers consisting of Om Puri, Smita Patil and

Mohan Agashe lent an additional dimension to the strong storyline and since it was in

Hindi, reached an India-wide audience directly, as Shatranj Ke Khilari had a few years

ago, as opposed to his masterpieces in Bengali, which could only reach

non-Bengalis through sub-titles.

But the beginning of the 80's also saw the deterioration of Ray's health. He fell ill with heart disease and the shooting of Ghare Baire was postponed . He had a bypass surgery and all Calcutta was anxious for his speedy recovery. In due course of time Ghare Baire was released and Victor Banerjee took young female hearts -- perhaps also some middle-aged ones -- by storm; there was hardly a girl in our school who did not fall under the spell of his mesmeric performance. The film was variously appreciated and some of my more conservative relatives saw in it an excess of liberality; the theme itself was perhaps too sensitive for some people's comfort. But Victor Banerjee as Nikhilesh stole the show; of this no one seems to have had the slightest doubt.

Earlier, on a visit to a shooting session, I had discovered that watching Ray direct a film on floor was perhaps no less a moving experience than watching his films on screen. The scene being shot was the one in which Soumitro Chatterjee, as Sandip, was being carried in a chair by his young followers on their shoulders, into the courtyard of Nikhilesh's ancestral manor house, thereafter to deliver a political speech. Ray in action on the floor resembled a great hurricane, sweeping and reordering all in its trail and wake. When his voice boomed "Silence!" and "Action!", a sudden and pervasive hush fell on the floor, and the actors began moving as though in a trance, under the magic wand of a conjuror. It was a memorable sight, forever to remain etched on my mind.

Ghare Baire created ripples which were dampened by news of Ray's heart disease and we all were concerned with his recovery; he was in his mid-sixties and physically still impressive, but his heart was malfunctioning. He was flown to the US and a bypass surgery was performed; he returned to Calcutta to a warm welcome. I still remember the milling crowds receiving him at the airport. He was erect and to our relief he showed no signs of frailty : the operation had been successful.

* * * * The mid-80's saw Ray struggling to keep himself active enough to be able to keep making films. By the mid-70's television had arrived in Calcutta and about a decade later I reached the age at which one could begin to appreciate, albeit in a tentative and fitful manner, the films that he had made in the 50's, 60's and early 70's, when they were shown on weekends on television. One may write volumes of his immortal earlier films, but here I address only those that he made in the 70's onwards : after the making of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, Ray's attention had turned to stories authored by young writers such as Sunil Gangopadhyay and Shankar : soon he made Aranyer Dinratri which he once placed amongst his three greatest films, though commercially it had not fared well in its first run. It is one of my favourites too, and somehow ties in with the theme of his last film Agantuk which though cinematographically rather restricted, is probably his most deeply thought-provoking film.

Pratidwandi (`The Adversary') was based on a story of Sunil, as was Aranyer Dinratri; it addressed the pressing problem of unemployment that had begun to bedevil Calcutta and Bengal from the second-half of the 60's onwards. The early 70's had been a time of unrest, and Ray could not remain aloof from the contemporary scene around him without making his own statements through his films.

Seemabaddha was a delicately crafted film based on the corporate world, and in it, Ray was unforgiving in his implied verdict; doubtless, his own earlier experience in working with D. J. Keymer had planted seeds in his mind to germinate, which grew into this film eventually.

He went back to the immortal Bibhuti Bhushan Bandyopadhyay with Ashani Sanket (`The Distant Thunder'); and once again, Soumitra Chatterjee, Ray's favourite lead actor put up a memorable performance. He was a few years later to be cast into the role of Felu-da, the detective, and we who were in our childhood in the 70's always saw Chatterjee as Felu-da and none else; it took me quite a few years to accept him wholeheartedly in his major roles in Ray's adult movies.

Jana Aranya was based on a story by Shankar; it too was concerned with the contemporary life of Calcutta; about a decade ago, Ray had made, Mahanagar, on a similar theme. Though it had ended on a note of hope, Jana Aranya ended on a shatteringly negative one: by the mid-70's, the ruthless world of commerce had impressed itself upon the mind of Ray with a harshness that was perhaps known less starkly to the younger Ray of the 60's.

Thus it was that I got to know the Ray of the early 70's only in the 80's, through repeated viewings of his films made in that period on the television.

* * * * However, in the mid-80's we all remained saddened by the fact that he was not being able to keep up his usual rate of a film a year and he was having to obey the restrictions imposed upon his movements by a team of doctors, which a man of action such as he was bound to find irksome; but he had no choice. He also had to cut down on his heavy smoking of earlier years and sadly, or perhaps amusingly, he was allowed to use his pipe only as an aid for thought and reflection : he held it between his teeth when working or musing, unlit and with a bowl totally destitute of tobacco.

By the end of the 80's because of his medical condition he had to choose subjects which could be dealt with predominantly through indoor dialogue. Ganashatru, an adaptation of Ibsen's An Enemy of the People carried a message which, in the Bengali cultural and religious setting, was powerful and compelling. It was followed by Shakha Proshakha which is likely to remain memorable for its remarkable prformances and dynamic dialogue. Ray had been concerned for long with the evolution of values in Bengali society in particular and modern society in general and in the 70's had voiced observations through Seemabaddha, Pratidwandi and Jana Aranya; Shakha Proshakha was a sequel to that series of films.

Ray's health was failing by the end of the 80's; it was at this time that he became deeply concerned with making a statement of his observations on civilization itself, and its contrast with barbarism, that must have floated around in his mind ever since his youth. These were profoundly philosophical considerations and not even the heights of success as an artist had dulled or deadened in him the keen edge of an invincible skepticism. Many aspects of the fabric of civilized human existence had provoked certain fundamental doubts in him and the primitive customs of aborigines began to hold an appeal to him as never before. Sadly, he seems to have realized that given the state of his health, it was perhaps unlikely that he could keep making films well into the 90's and probably realized that time was running out for making a clean breast of his critically philosophical speculations through a film : Agantuk was the result.

It is here that the informed chronicler of Ray's working life in the 70's and 80's

must take his leave of his audience; for Agantuk deserves an entire detailed essay in

its own right. Anyone who wishes to know Ray's mind must meditate upon this film

carefully and a cursory account can only do it injustice.

It is here that the informed chronicler of Ray's working life in the 70's and 80's

must take his leave of his audience; for Agantuk deserves an entire detailed essay in

its own right. Anyone who wishes to know Ray's mind must meditate upon this film

carefully and a cursory account can only do it injustice.

As it happened, Ray did not survive well into the 90's. Years ago he had been asked in an interview how long he intended to keep making films; he had replied that if he lived to be ninety, probably he would be directing till he was about eighty. That was not to be : his decease in 1992 marked the end of a glorious era of the art and culture of our times, of which we who lived in the same Calcutta that he inhabited can feel justly proud.

* * * *  During the 70's and 80's, Ray kept up his familiar and characteristic alternation

between the contemporary and the period or eternal. The films on the Calcutta that

spread out and bustled with restless life around him was captured in its many moods

vividly in his films; and period movies such as Shatranj Ke Khilari and Ghare

Baire sought to address eternal themes against a historical backdrop. Looking across

the vast canvas of his films made in these two decades, I fail to resist the conclusion

that it was in the latter category that his principal triumphs lay; Pratidwandi and

Jana Aranya are imoportant films, but I doubt whether, say in the year 2025, half a

century after they were made, they would be viewed with as much involvement and

interest as the period films are likely to be. This is perhaps inevitable; and it is the Ray

musing on eternal themes, rather than the Ray scrutinising the problems and

perplexities of the contemporary scene, that seems all set to

remain a figure casting a profoundly influential impact on our cultural life in the

new century.

During the 70's and 80's, Ray kept up his familiar and characteristic alternation

between the contemporary and the period or eternal. The films on the Calcutta that

spread out and bustled with restless life around him was captured in its many moods

vividly in his films; and period movies such as Shatranj Ke Khilari and Ghare

Baire sought to address eternal themes against a historical backdrop. Looking across

the vast canvas of his films made in these two decades, I fail to resist the conclusion

that it was in the latter category that his principal triumphs lay; Pratidwandi and

Jana Aranya are imoportant films, but I doubt whether, say in the year 2025, half a

century after they were made, they would be viewed with as much involvement and

interest as the period films are likely to be. This is perhaps inevitable; and it is the Ray

musing on eternal themes, rather than the Ray scrutinising the problems and

perplexities of the contemporary scene, that seems all set to

remain a figure casting a profoundly influential impact on our cultural life in the

new century.

Illustrations : Rajat Baran Chakraborty

Published November 15, 2002

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us